A Trove of Historic Jazz Recordings has Found a Home in Harlem, But You Can’t Hear Them

Illustration by Terry Allen

The swing era lasted barely a decade—roughly the mid-1930s until the end of World War II—but it was a golden age for jazz.

It was the only time that jazz dominated American popular music. Legendary musicians who had helped invent the music—the likes of Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, Lester Young, Bunny Berigan and Coleman Hawkins—still were in their prime. And they could be heard everywhere: swank hotel ballrooms, homecoming dances on college campuses, radio programs—but especially at cramped, smoky nightclubs in such musical hotbeds as Chicago, Kansas City and New York City. In those clubs, jazz musicians honed their craft during lengthy jam sessions, where a player might improvise on chorus after chorus of standards like George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm,” or on their own compositions or blues riffs made up on the stand.

But the only people who got to hear their jazz heroes stretch out and work through new musical ideas in those impromptu blowing sessions were those sitting in the audience. In those days, technology limited recordings to a window of only about three minutes, the amount of music that could fit on 78 rpm records. The ability to record extended performances by the era’s jazz greats simply didn’t exist.

Or so it was thought.

It turns out that one man—a jazz musician and technical genius—figured out a way. But during his lifetime, William Savory kept these recordings largely to himself. He refused to reveal how many recordings he had and what performances they contained. He let only a very few of his recordings be heard by a small number of acquaintances. Over time, the Savory collection became a tantalizing enigma to jazz connoisseurs who yearned for access to its treasures.

The mystery ended last summer. Six years after Savory passed away, his collection was acquired by the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. And jazz experts were stunned. The extent and quality of the Savory collection was beyond anything they had imagined.

“I figured there was maybe 50 to 100 unreleased recordings,” says Loren Schoenberg, the museum’s executive director. “I expected to see one box. Instead, I saw dozens of boxes. The Savory collection comprised about a thousand discs of the greatest performers of all time. And all of this was unknown music. It was immediately clear this was a treasure trove.”

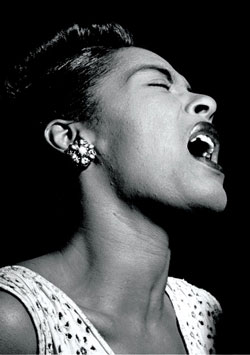

Photo of Billie Holiday courtesy of William P. Gottlieb Collection, Library of Congress

Among the treasures: Coleman Hawkins, the first great tenor saxophonist in jazz, playing multiple ad-lib choruses on the classic “Body and Soul.” Billie Holiday, accompanied only by piano, singing a moving rubato version of “Strange Fruit,” a chilling musical condemnation of lynching. The Count Basie Orchestra performing at the world’s first outdoor jazz festival, the 1938 Carnival of Swing on Randall’s Island in New York City. Basie’s tenor sax stars, Lester Young and Herschel Evans, sharing solos on “Texas Shuffle.” Benny Goodman and Teddy Wilson—on harpsichord instead of his usual piano—performing “Lady Be Good!” And the list goes on.

The collection is, in a word, historic. “It is a wonderful addition to our knowledge of a great period in jazz,” says Dan Morgenstern, director of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University in Newark, N.J. And, Morgenstern says, “the sound quality of many of these works is amazing. Some of it is of pristine quality. It is a cultural treasure and should be made widely available.”

The question, however, is whether that will happen anytime soon. And if it doesn’t, music fans might be justified in putting the blame on copyright law. “The potential copyright liability that could attach to redistribution of these recordings is so large—and, more importantly, so uncertain—that there may never be a public distribution of the recordings,” wrote David G. Post, a law professor at Temple University in Philadelphia, on the Volokh Conspiracy blog. “Tracking down all the parties who may have a copyright interest in these performances, and therefore an entitlement to royalty payments (or to enjoining their distribution), is a monumental—and quite possibly an impossible—task.”

ORPHANS IN LIMBO

This problem isn’t unique to the Savory collection. Many other musical performances, books, movies and photos also are in copyright limbo, making it difficult for museums, libraries and other organizations to preserve, display or sell these “orphan” works.

In January 2006, the U.S. Copyright Office issued a Report on Orphan Works that describes the general scope of the problem and outlines possible solutions. “The orphan works problem is elusive to quantify and describe comprehensively,” states the report, but “the problem is real.”

The report notes that many historically significant images are removed from documentaries and never reach the public because the copyright owners of these images cannot be determined. Museums possess millions of archival documents, photographs, oral histories and reels of film that they cannot publish or digitize because copyright ownership is unclear.

In its report, the Copyright Office proposed a solution to the orphan works problem that became the framework for several bills introduced in Congress.

But the bills never made it through, and now it appears unlikely that Congress will address the issue in the near term.

Some wonder whether Google might hold the key to a solution. The search giant is attempting to create a huge database of books that could be searched or read online—including works of uncertain copyright ownership. But Google’s plan is controversial, and a recent federal court ruling puts its future in jeopardy.

Photo of Coleman Hawkins with Miles Davis courtesy of William P. Gottleib Collection, Library of Congress

THE ROAD TO MALTA

By all accounts, William Savory was a talented man. Even as a teenager starting out in the music business, he displayed an uncommon technical expertise. He had gone to a Manhattan recording studio to make a demo with a band he was in, but the studio’s equipment didn’t work. He repaired it and was subsequently hired to maintain the equipment.

In the late 1930s, while working as a technician on radio broadcasts, Savory began to record them for himself. Because of his expertise, Savory’s recordings were far superior to others made at the time. The typical practice was to record on 10-inch 78 rpm shellac discs, which could hold only about three minutes of music. Savory, however, used discs that were larger, made of more durable materials and sometimes recorded at slower speeds (33 rpm). As a result, he was able to re-cord longer musical performances.

Savory stopped recording in 1940, when he changed jobs and moved to Chicago. During World War II, he helped develop radar for the U.S. government. After the war, as an employee of Columbia Records, he helped create the 331⁄3 rpm long-playing record. In the 1950s, he engineered and produced classical music albums for Angel Records. Then he moved to Falls Church, Va., and worked on electronic communications and surveillance devices that were, reportedly, used by the CIA.

By the time Savory died in 2004, many of his recordings were deteriorating. Some of the boxes they were stored in had water damage; others were covered with mold. The entire collection was almost thrown away.

The collection was saved by Savory’s son, Eugene W. Desavouret (Savory’s original name). Desavouret sent his daughter to bring the boxes of recordings back to his home in Malta, Ill. He stored them in his living room for the next five years.

Meanwhile, Schoenberg had been seeking access to the Savory collection for decades. “I met Bill Savory in 1980, when I went to work for Benny Goodman,” Schoenberg says. “I knew he had some unreleased recordings of Goodman when he had some wonderful musicians with him. I was at Savory for 24 years, until he died, to let me hear the music.”

Schoenberg continued his quest after Savory’s death. Eventually, he tracked down Savory’s son. And last spring, Schoenberg visited Desavouret in Malta, where he finally saw the collection. Soon thereafter, the National Jazz Museum in Harlem purchased the collection.

Schoenberg himself drove the large truck that hauled the collection to New York City. “I was nervous about it,” he says. “I was nervous about an accident. I was nervous about a flat tire. Even when we were backing it into the storage facility in Manhattan on the next evening, I was worrying about whether a garage door might come down.”

Schoenberg estimates that a quarter of the collection is in excellent condition, half of it suffers from significant deterioration but can be fixed, and the rest is in very poor shape. To prevent further deterioration and restore the audio quality of the recordings, the museum is digitizing the collection.

The public has only limited access to these digitized versions, however. Eight short clips, lasting about 30 seconds each, can be heard on the museum’s website. To hear anything more, you have to make an appointment to visit the museum’s listening room.

Schoenberg is determined to bring the Savory collection to the public, but he knows it will be a challenge.

“We’re in discussion with a couple of record companies,” he says. “There are, of course, legal hurdles to be cleared. It is a pretty murky enterprise. There don’t seem to be definitive rules.”

Perhaps the biggest hurdle will be getting permission from the recordings’ copyright owners—if they can even be identified. That will be no mean feat because there are so many parties involved, and their rights often are unclear.

Photo of Count Basie courtesy of William P. Gottleib Collection, Library of Congress

THE COPYRIGHT MAZE

Sorting through those kinds of copyright issues can be a long and expensive process, bedeviling many who wish to use orphan works. Even organizations dedicated to handling copyright interests, such as the Harry Fox Agency in Manhattan, have trouble locating copyright owners. The agency was set up by the music publishing industry to administer the collective licensing of musical copyrights, but it has lost track of hundreds of music publishing companies that may be entitled to royalty payments.

If an organization wishes to use a copyrighted work, but no copyright owner can be found, the organization has a choice. It can forgo using the work, or it can use the work without permission, gambling that no copyright owner will appear.

But if the organization loses that gamble, the costs can be high: treble damages for willful infringement and an injunction against any further use of the work.

Many museums, libraries, filmmakers and others will not gamble on using orphan works. “Many users of copyrighted works have indicat-ed that the risk of liability for copyright infringement, however remote, is enough to prompt them not to make use of the work,” states the 2006 Copyright Office report.

“Such an outcome is not in the public interest, particularly where the copyright owner is not locatable because he no longer exists or otherwise does not care to restrain the use of his work.”

Congress has done little to remedy the situation. If anything, bills adopted over the past 25 years have exacerbated the orphan works problem, some experts say.

“We used to have a system that said you didn’t get a copyright unless you registered your work or put on a copyright notice,” says Jessica Litman, a professor at the University of Michigan Law School in Ann Arbor. “In 1976, we changed all that. Copyright is now automatic.” As a result, many copyrighted works now lack any easily accessible data about their copyright owners, she says.

Under the 1909 Copyright Act, federal copyrights lasted 28 years and could be renewed for an additional 28 years. But studies indicate that the renewal rate was never more than 22 percent, so most works received copyright protection only for the initial 28-year period.

The 1976 Copyright Act did away with renewals and created a single, much longer term of copyright protection. For works set down in a fixed form on or after Jan. 1, 1978, the statute granted copyright protection for the life of the author plus an additional 50 years. For works of corporate authorship (primarily works for hire), the law granted copyright protection for 75 years from the date of publication or 100 years from creation, whichever came first.

Congress further increased the copyright term in 1998. The Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act tacked on an additional 20 years to all periods of copyright protection. Under the law, an author’s work is now protected for life plus 70 years, while works of corporate ownership are protected for 95 years from publication or for 120 years from creation.

Works that were created before 1978 and covered by the 1909 Copyright Act did not benefit from these changes. But those works had benefited earlier. In 1992, Congress made copy- right renewals automatic for works covered by the 1909 act.

As a result of these changes—many of which were adopted by Congress to accommodate obligations under international treaties—a large number of works that otherwise would have fallen into the public domain over time may be used only with copyright owners’ permission. Moreover, longer copyright terms mean that copyright searches must go back further in time, making it harder to track down the copyright interests of individuals who may have moved or died, or corporations that may have merged, sold their assets or gone bankrupt.

In its 2006 report, the Copyright Office described the orphan works problem as “a byproduct of the United States’ modern copyright system [that] has been with us since at least the day the 1976 act went into effect.”

But some orphan works fall outside the scope of federal law, and their use is governed by state law.

Consider, for instance, the recordings made by Savory. The songs the musicians played might have been registered with the U.S. Copyright Office and protected by the 1909 Copyright Act, but the recordings themselves are not covered by federal copyright law.

It wasn’t until 1971 that Congress amended the law to cover sound recordings, but that gave federal copyright protection only to recordings made on or after Feb. 15, 1972. Prior recordings are protected only by various state laws.

In its 2006 report, the Copyright Office urged Congress to enact legislation that would protect any entity that is unable to locate a copyright owner after conducting a “reasonably diligent search.” If the entity subsequently uses the work and is sued for infringement by the copyright owner, the entity would not be liable for statutory damages or willful infringement. Instead, it would have to pay only “reasonable compensation” —in other words, a reasonable license fee. Moreover, the entity would not pay anything if it uses the work for noncommercial purposes and expeditiously stops using the work after receiving notice from the copyright owner. The Copyright Office also called for limits on injunctive relief for copyright owners in orphan copyright cases.

“The Copyright Office felt this was a reasonable balance because it wouldn’t put orphan works into the public domain, but would minimize the risk of using such works if and when their owners came up,” says Hillel I. Parness, a partner at Robins, Kaplan, Miller & Ciresi in New York City.

Soon after the Copyright Office issued the orphan copyrights report, a bill incorporating its proposals was introduced in the House of Representatives; but it never made it out of the Judiciary Committee. In 2008, similar legislation was introduced in the House and Senate. The Senate unanimously passed the bill; but again, the measure never made it out of the House Judiciary Committee.

A major reason why these bills stalled was opposition from organizations representing professional photographers, whose works are usually published without any attribution or copyright notice. “That’s why the photographers’ refrain is that their photos are orphans from the moment they are put in the stream of commerce,” says Ralph Oman, who teaches at the George Washington University Law School in Washington, D.C., and serves on the council for the ABA Section of Intellectual Property Law. “They fear that if orphan works become the preferred means of finding photos, they won’t get new work,” Oman says.

Photographers are not the only ones fretting about the legislation. “Visual artists and textile creators are worried that their works may not be easy to search, making it hard to identify the copyright owners of these works,” says Dale Cendali, a partner at Kirkland & Ellis in New York City and vice-chair of the Copyrights Division in the IPL section. “They are worried that if orphan works legislation passes, they will be put in a worse position than if there were no legislation.”

Photo of Bennie Goodman courtesy of William P. Gottleib Collection, Library of Congress

LET GOOGLE FIX IT

For a while, it appeared as if Google might solve the orphan works problem without the help of Congress. But the company’s plans suffered a serious setback March 22, when a federal district court in New York rejected the proposed Google Books settlement.

The idea behind Google Books is simple: If all the world’s books are digitized and put online, anyone can easily find the information they need.

To some, this sounds like a noble, if utopian, goal. But to many publishers and authors, it sounds like massive copyright infringement. So in 2005, about nine months after Google announced it was partnering with some major libraries to digitize their collections and put them online, the Association of American Publishers and the Authors Guild sued the search giant in federal court.

The parties in the class action reached an innovative settlement that would have allowed Google to fully display every book published in the United States and registered with the Copyright Office before Jan. 6, 2009— with the exception of those books whose authors or publishers expressly opted out of the settlement.

Under the settlement, Google could display any book in the public domain; display a copyrighted book that is in print, provided the copyright holder authorizes such use; and display a copyrighted book without the copyright holder’s authorization if the book is out of print.

In return, Google would have paid participating authors and publishers a total of at least $45 million for scanning their works without permission before the settlement, plus 63 percent of revenues received from Google’s commercial use of the books, such as ad sales alongside book selections.

Google also would have paid $34.5 million to establish and maintain a book rights registry. This nonprofit would create a database of rights and contact information for authors and publishers, distribute payments from Google to authors and publishers, and attempt to locate those with rights in orphan works.

Royalty payments unclaimed after five years would be used first to support operations of the registry. Any remaining funds would be used for charitable purposes consistent with the interests of publishers and authors.

Although the settlement covered only books registered with the Copyright Office, it would have allowed Google to use a large number of orphan works, because it is often hard to determine who now owns the copyright in out-of-print books.

The settlement went too far for Judge Denny Chin, who had heard the case as a district court judge and maintained responsibility for it even after he had been elevated to the Manhattan-based 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. He rejected the settlement agreement largely because it turned copyright law on its head; instead of requiring Google to obtain permission to use copyrighted works, the agreement required copyright owners to stop Google from using their works (by opting out of the settlement).

Chin suggested a solution: Change the settlement from opt out to opt in. If the settlement applies only to authors and publishers who opt in to its terms, many of the settlement’s problems “would be ameliorated,” wrote Chin in his opinion.

Many experts, however, doubt Google would accept such an opt-in settlement. “It would be of absolutely no use to Google, because it is a pretty impossible task to find out who owns the rights in all these works and get permission to use them,” Litman says.

WHAT NOW?

In the wake of Chin’s ruling, many expect Google and other interested parties to turn their attention back to Capitol Hill—and try once more for legislation on orphan works. This time, however, they may urge Congress to take a new approach.

“The approach Congress was taking before was if you can’t find the author after a diligent search, you can freely use the work; and if the author shows up, you may need to stop using the work and/or pay a reasonable license fee,” says Pamela Samuelson, a director of the Center for Law & Technology at the University of California at Berkeley’s Boalt Hall.

“One aspect of the Google Books settlement provides another model Congress might be willing to consider: allowing use of works that may be orphaned as long as the user pays for the use, with some of the funds used to search for the rights owner,” she says. “This borrows a little from the Google Books model, but isn’t limited to just one company. When a work is an orphan it should be available for everyone to use.”

There are now powerful forces in favor of orphan works legislation, but their success is far from certain.

“The combined lobbying power of book publishers, high-tech interests and some of their allies might suffice to get an orphan works bill through,” Litman says. “But it would take an immense push in a Congress that seems much more interested in intensely political issues like taxes.”

So it remains unclear when—if ever—the orphan works problem will be solved.

Jazz aficionados hope such a wait won’t keep the musical jewels of the Savory collection locked away. “This music is not just of interest to historians or academics,” says Morgenstern of Rutgers. “It is wonderful music. Anyone with an ear for jazz would love to hear it.”

Steven Seidenberg is a lawyer and freelance journalist in Fanwood, N.J., who contributes regularly to the ABA Journal.