Afghan and Iraqi interpreters for the US are caught in a deadly immigration waiting game

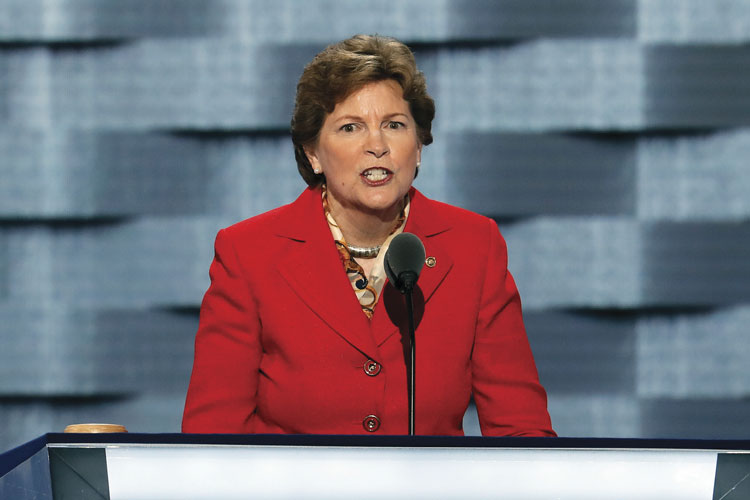

Sen. Jeanne Shaheen, D-N.H.: “For these Afghans, it really is no exaggeration to say that this is a matter of life and death.” Photo by Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via AP Images.

Political Football

That settlement was announced in March 2016, and no similar high-profile case has followed. Instead, SIV advocates have turned their focus to a different problem: increasing the number of visas available in the Afghan SIV program.

That program is authorized to issue 8,500 visas by the end of 2020. But in March, the State Department announced that it would stop conducting visa interviews under the program because the number of already pending applications was enough to claim all remaining visas.

According to a Congressional Research Service brief, there were 1,908 visas available under the program as of Jan. 29. But the State Department said as of Dec. 13, 2016, there were more than 13,000 applications pending. That means there were, at that time, about 11,000 Afghans who wouldn’t get visas, even if they qualify.

SIV advocates predicted that gap well in advance. Indeed, the State Department asked Congress to authorize 4,000 more visas in fiscal year 2017. (Cooper says the extra visas must be funded with appropriations; thus, the agency cannot unilaterally issue more.) But the NDAA for fiscal 2017 passed the House of Representatives with no new visas.

Advocates for the program hoped that the Senate would intervene when it got the bill in the summer of 2016. The Senate Armed Services Committee includes two longtime advocates for the SIV programs in Shaheen and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. Those legislators, plus Sens. Jack Reed, D-R.I., and Thom Tillis, R-N.C., did try to pass an amendment to the NDAA that would have authorized 4,000 more visas. (All four are on the committee; McCain and Reed are veterans.)

They had to get agreement from the Senate Judiciary Committee, whose chairman is Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa, and whose immigration subcommittee chair was at that time Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala., who is now U.S. attorney general. Both opposed that many new visas, citing concerns about costs, security screening and whether that many new visas were needed. As a compromise, Shaheen and McCain agreed to 2,500 new visas.

Even that smaller number failed to pass the Senate, despite its bipartisan support. Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, blocked passage of several NDAA amendments in June 2016 in an effort to get consideration of an unrelated amendment. That upset McCain, who suggested on the Senate floor that if an Afghan ally was killed as a result, there would be blood on Lee’s hands.

“People are going to die, I tell the senator from Utah,” McCain said, in remarks broadcast on C-SPAN June 9, 2016. “They’re going to die if we don’t pass this amendment and take them out of harm’s way. Don’t you understand the gravity of that?”

The Senate recessed for the summer without passing either amendment. Ultimately, the committee that reconciles the bills passed by the two houses of Congress authorized 1,500 more visas—a number that supporters knew would not be sufficient. This spring, Shaheen, McCain, Reed and Tillis introduced a bill that would add 2,500 more visas.

“For these Afghans, it really is no exaggeration to say that this is a matter of life and death,” Shaheen said, according to the Congressional Record. “Interpreters who served the U.S. mission are being systematically hunted down by the Taliban; and unless Congress acts, this program will lapse, and we will abandon these Afghans to a harsh fate.”

Shaheen’s remarks also referenced the other major political obstacle to the SIV program: Trump’s executive orders on travel from majority-Muslim countries. As she noted, the original “travel ban” barred Iraqis from entering the country for 90 days—with no exemption for SIV holders. One of the first high-profile cases related to the ban concerned an Iraqi SIV holder detained at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport for 18 hours.

A backlash—from the military as well as immigrant advocates—quickly led to an exception for SIV holders. The second executive order, issued in early March, left Iraq off the list of countries whose citizens would be barred. However, because the Iraqi SIV program is closed to new applicants, many former allies were trying to get in as refugees. This approach has been blocked by the refugee provision of the president’s executive order.

Scott Cooper: “It’s a 14-step process, and the delays, quite honestly, are a lack of ability to get them processed.”

DETENTION QUESTIONS

And while Afghan nationals were never banned, there’s evidence that in practice, if not by law, Afghan SIV holders have problems entering the United States. In two incidents in March, U.S. Customs and Border Protection detained and attempted to deport Afghans with valid SIVs.

At least one of these SIV holders, a man detained at Newark International Airport, remains in custody as of press time, and—because authorities convinced him to sign a document relinquishing his visa—has been forced to file for asylum to avoid deportation.

These detention cases are sealed, and the federal government declined to comment publicly on either, except to say that CBP officers may further scrutinize visa holders at their discretion. Increased news reports of arbitrary denials of entry, aggressive Immigration and Customs Enforcement arrests and more suggested that the agencies were indeed flexing their muscles in the weeks following the inauguration.

The International Refugee Assistance Project’s communications manager, Henrike Dessaules—whose organization has worked with SIV holders for years—points out that this kind of treatment is new.

“We can only assume that this has something to do with CBP using their discretionary powers,” she says. “Maybe this will be the new reality for our clients.”

Amin has been working to settle into his own new reality. Just after his arrival in the U.S., he was living with the Ball family and waiting for his green card, which would allow him to work. He has plans to go back to school and earn a master’s degree to further his undergraduate degree in business.

But the fate of other U.S.-Afghan allies remains uncertain. The Trump administration has taken a hard line on immigration, particularly from majority-Muslim countries—but it has also shown a willingness to pursue military priorities.

Cooper, the retired Marine now with Human Rights First, says that veterans, as a rule, care a great deal about the SIV program.

“I think you are hard-pressed to find anyone who served in uniform that doesn’t ... support the special immigrant visa program. It’s almost unanimous,” he says. “I’ve never heard anyone that served over there that hasn’t said that absolutely, these folks deserve to come in here—they saved our lives.”

Correction

Print and initial online versions of “Forgotten Allies, Broken Promises,” September, should have stated that Afghans may apply for special immigrant visas even after all available SIVs have been awarded, but the State Department will not schedule interviews until more become available. It also should have reported that President Donald Trump's executive order blocks Iraqi nationals from entering the United States as refugees.The Journal regrets the errors.

This article was first published in the September 2017 ABA Journal magazine with the headline "Forgotten Allies, Broken Promises."