Shut up! The art and craftiness of cease-and-desist letters

Photos courtesy of Vince Grzegorek/Cleveland scene; Everett collection/Shutterstock.com

getting snarky

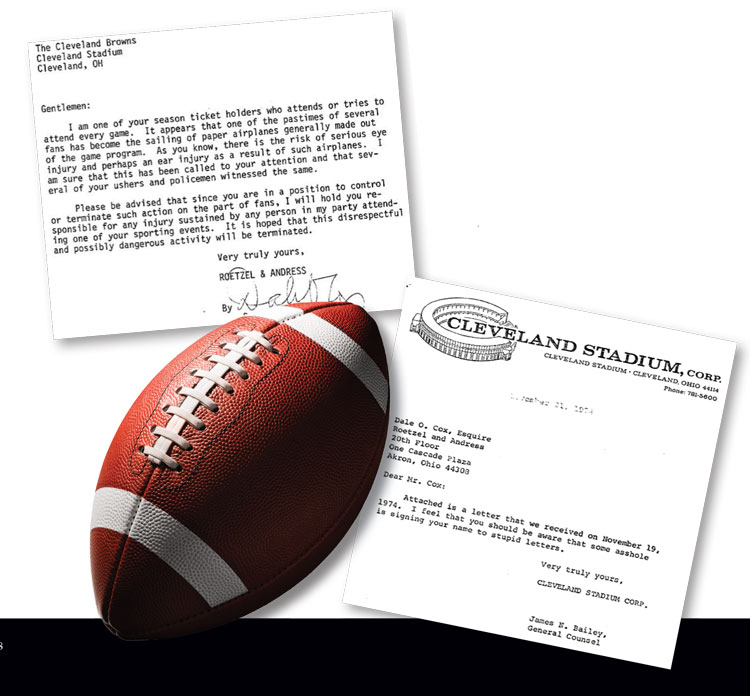

The push and pull of demand letters with threats—and sometimes sarcastic humor, as well as responses—isn’t new, of course. Nor is an in-your-face ironic touch, as seen in some classic volleys from 1974 between a fan and the general counsel for the stadium of the National Football League’s Cleveland Browns.

Dale O. Cox—then a lawyer in one of Akron, Ohio’s better-known firms, Roetzel & Andress—wrote that some fans were regularly throwing paper airplanes during games, and that he would hold the stadium respon-sible for any injuries they might cause to the eyes of himself or those in his party.

Cox got a quick, two-sentence response from general counsel James N. Bailey: “Attached is a letter that we received on Nov. 19, 1974. I feel that you should be aware that some asshole is signing your name to stupid letters.”

Now living in Orofino, Idaho, Cox laughs at the memory and admits he engaged in a bit of pretext about the paper planes.

“That wasn’t the real problem,” he says. “I had great seats on the second level, and when the guys stood at the rail in front of me to throw paper airplanes they blocked the view of the playing field. But after I pointed out the dangers, it did stop.”

Such pointed ripostes seem to have become more common in our own age of snark and ease of email.

One of the best examples in recent years is a lawyer’s response to the counsel for West Orange, New Jersey. Richard Trenk’s letter demanded that a critic of the town council take down his website at westorange.info because it is “unauthorized and is likely to cause confustion (sic).”

Attorney Stephen Kaplitt’s lengthy response is a cascade of comedic flame, including: “Obviously it was sent in jest, and the world can certainly use more legal satire. Bravo, Mr. Trenk!” Thus, “it was certainly not some impulsive, ham-fisted attempt to bully a local resident solely because of his well-known political views.

“After all, as lawyers you and I both know that would be flagrantly unconstitutional and would also, in the words of my 4-year-old, make you a big meanie.”

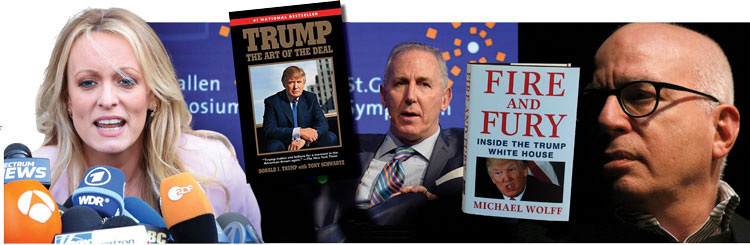

A number of lawyers representing Donald Trump have issued tough demand letters in efforts to silence the adult film actress Stormy Daniels, whose legal name is Stephanie Clifford; Tony Schwartz, who penned the 1987 book “Trump: The Art of the Deal” but made the media rounds more recently as a Trump critic; and author Michael Wolff, whose gossipy, revelatory and detailed book is called “Fire and Fury.” Photos by AP Photo; J. Stone, Kathy Hutchins, 360B/Shutterstock.com.

Setting boundaries

But demand-type interactions typically aren’t such light affairs. The question then becomes: What are the boundaries?

One of the best-known for pushing them is Martin Singer, a Los Angeles lawyer for stars such as Scarlett Johansson, Charlie Sheen, John Travolta and Bruce Willis.

Singer’s tactics and letters are notorious and widely feared. One of his clients perhaps put it best in a tribute speech in 2012, when Singer was awarded the Beverly Hills Bar Association’s Entertainment Lawyer of the Year award.

“You call Marty because you need someone like Mike Tyson in the Holyfield fight, when he bit his ear off,” actress Sharon Stone told the gathering, according to the Hollywood Reporter. “Marty is such a badass motherfucker.”

Last November, California’s 2nd District Court of Appeal drew a sharp boundary for Singer, ruling that a former model who said on Entertainment Tonight that Bill Cosby raped her could sue Singer for defamation. The ruling was based on his subsequent news release saying she lied and more of the same in what the court called his “hollow threats” to other news organizations interested in the story.

In Dickinson v. Cosby, the court pointed out that Singer never sued any media outlet for running the story, and that “the demand letter was a bluff intended to frighten the media outlets into silence (at a time when they could still be silenced), but with no intention to go through with the threat of litigation if they were uncowed.”

The court noted that Janice Dickinson added Singer in an amended complaint after learning through disclosures that he might not have asked Cosby whether the accusations were true before lashing out at her and the media.

Singer wrote in his demand letter to news organizations that she was “seeking publicity to bolster her fading career.” His subsequent news release said she lied.

Rebecca Roiphe: “It seems more important now that facts come out, and lawyers are contributing to the truth being buried.” Photo courtesy of New York Law School.

The California Supreme Court denied a petition for review in March, letting the defamation cases proceed against both Cosby and Singer. The same court had let Singer off the hook in 2013 on a question of extortion in a demand letter.

Singer represented a part owner of some Hollywood restaurants and nightclubs, suing two of his client’s business partners for misappropria-tion of over $1 million. He attached a draft complaint to the letter, with information about the defendants “using company resources to arrange sexual liaisons with older men … and many others.” It included details about “fetish role-play fantasies” with father-son and uncle-nephew themes.

The appeals court, in absolving him, found the facts in Malin v. Singer to be fundamentally different from the measure for extortion laid out in the state supreme court’s 2006 decision in Flatley v. Mauro.

In Malin, the embarrassing information about sexual activities was pertinent to the case because that’s where the allegedly misappropriated funds went. But in Flatley, the state’s high court found there was extortion when a lawyer’s demand—for “ ‘seven figures’ or, at a minimum, $1 million”—included the threat that failure to settle could lead to an investigation of personal assets that would be exposed to the IRS and other federal and local agencies, as well as those in some other countries.

The court said the threat to disclose criminal activity unrelated to any alleged injury “is itself evidence of extortion.” Illinois lawyer D. Dean Mauro’s license was suspended for a year.