Attorney's book recounts how he helped bring US military involvement in Vietnam to an end

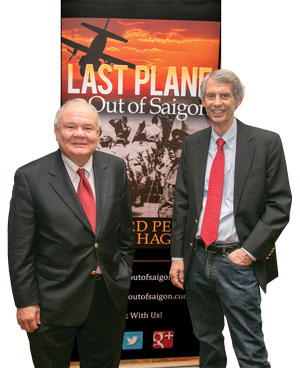

Co-authors Richard Pena and John Hagan spoke about their collaboration at the midyear meeting in Houston. Photo by Kathy Anderson.

Pena had used the briefcase during his first year in law school at the University of Texas at Austin, but his legal education was cut short when he was drafted in 1970 and then slated for duty in Vietnam—not as a legal clerk, as he expected, but as a medical technician in the surgery department of the last U.S. military hospital still operating as American involvement in the war was winding down in the early 1970s. When Pena shipped out for Vietnam in May 1972, the briefcase went with him. “That briefcase was my security blanket in Vietnam,” says Pena, who is now president and CEO of the Law Offices of Richard Pena in Austin.

In addition to the comfort Pena got from a seemingly mundane item from home like a briefcase—clearly, he was a lawyer at heart even then—he also kept a journal to help him cope with and comprehend an environment that made little sense to the grunts who still were “in country” during the closing days of America’s military involvement in Vietnam.

But the journal wasn’t actually a diary or chronicle of Pena’s months in Vietnam so much as it was a collection of short essays written at various points that express his thoughts about the war, the people he served with, his hospital experiences, the relationship between American soldiers and average Vietnamese citizens, and why the United States became involved in Vietnam in the first place. “It gave my real impressions on the ground of the war and my feelings about it,” he says.

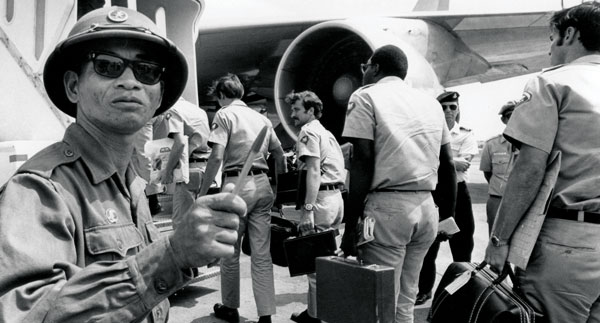

Photo by AP Photo/Neal Ulevich

Photo of co-authors Richard Pena and John Hagan by Kathy Anderson

GROWING DOUBTS

One of the themes expressed in Pena’s entries is a growing skepticism about official authority. In Vietnam, Pena writes in an entry from late 1972, “extreme existentialism is not merely a vague concept, but instead a way of life. The immediate is all that matters. Memories of the past are but vague dreams; the future is light-years away. As each day passes, the hope of seeing your family and friends diminishes, as does your grasp on what reality is like in ‘the world.’ Although this situation generally prevails in the participants of any war, in Vietnam it feeds on the lies, the betrayals and the corruption typifying the entire war.”

Pena also describes how he became one of the American soldiers walking toward the “last plane out” in the photo at the War Remnants Museum.

After months of negotiations between U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and representatives of the governments in North and South Vietnam, the Paris Peace Accords were signed on Jan. 27, 1973, signaling the end of active U.S. military involvement in the war, which cost some 58,000 American lives.

Among other provisions, the accords called for the United States to withdraw its remaining forces, which then numbered some 65,000, within 60 days. Only a tiny contingent would be left behind to guard the U.S. embassy in Saigon and a few other civilian government installations. (Embassy staff members fled in April 1975 as North Vietnamese troops were entering Saigon in the final battle of the war.)

The pullout started the very next day. Every soldier was issued a card indicating the day of their evacuation, but Pena and one other orderly at the hospital were issued cards that read “X+61,” which indicated that their departure technically would be one day later than required by the peace accords. The explanation they were given was that they were needed to handle any last-minute emergencies at the hospital. He remembers that one of his commanding officers told him, “Soldier, you are going to turn the lights out on Vietnam.”

A few weeks before departing, Pena wrote in his journal: “Leaving is not at all the way I had imagined it would be. There is not the ecstatic happiness which I had anticipated. There is no smiling, by me or by others. There is not even the lifting of a burden. In these last days before departing, I realize that the weight I have carried for the past 11 months will never be lifted from my shoulders.”

Pena was discharged shortly after returning from Vietnam in late March of 1972, and he says the return to civilian life was not easy. “I was angry,” he says. “I was angry the whole time after I got back. It did pass, but I was cold. I had my walls up.”

Shutterstock.com

REAL-WORLD SUCCESSES

Pena turned out to be one of the lucky ones whose psychic wounds eventually healed. He returned to law school at the University of Texas, where he received his JD in 1976, then went into practice in Austin, where he represents plaintiffs in personal injury and workers’ compensation cases. He went on to serve as president of the Austin Bar Association and the State Bar of Texas, and served as a member of the ABA’s Board of Governors and House of Delegates. He also is a past president of the American Bar Foundation. And he became involved in the People to People Ambassador Program (his firm now supports Legal Delegations Abroad, which sponsors overseas trips by U.S. lawyers), which led to his return trip to Vietnam in 2003.

After returning from that trip, Pena began talking about his wartime experiences in Vietnam with John Hagan, who is co-director of the Center of Law & Globalization at the American Bar Foundation. “And John said, ‘You should write a book,’ ” says Pena, who subsequently dug out his Vietnam writings, which had languished in various drawers and closets for some 40 years after he returned. He gave the work to Hagan, who called back a few days later and urged him to publish it.

“We all have our own stories from that period,” says Hagan. “It’s extraordinarily important that we remember, understand and try to come to terms with that experience. As soon as I had read what he had written, I was struck by its honesty, sincerity and, frankly, the quality of the writing.”

Pena and Hagan began working together to polish the manuscript. While Pena’s entries written in Vietnam stayed pretty much unchanged, Hagan wrote a handful of short chapters that provided historical context. The manuscript was picked up by Story Merchant Books in Beverly Hills, California, which published it in 2014 with the title Last Plane Out of Saigon. The American Bar Foundation sponsored a book signing during the ABA Midyear Meeting in Houston.

While publishing the book has been therapeutic, Pena says, his Vietnam experiences still have left their mark on him. On the one hand, he says, he thinks he is a better, tougher lawyer. As he puts it, “I don’t care what people say. What are they going to do, send me back to Vietnam?”

But Pena says he remains skeptical about America’s military involvement in more recent wars, especially in the Middle East, and he sees a tough road ahead for many veterans of those conflicts. “War is war,” he says. “It’s an insane existence, and the whole game is to survive, both physically and mentally.” Pena, who is working with the Texas bar to re-energize its Texas Lawyers for Texas Veterans legal clinics, cites high rates of suicide, post-traumatic stress disorder and addiction among veterans returning from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“My only advice,” Pena says, “is ‘Hold it and roll.’ That means do the best you can. Tomorrow may be a better day.”

This article originally appeared in the June 2015 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Shut the Lights Off Before You Leave: Attorney’s book recounts how he helped bring U.S. military involvement in Vietnam to an end.”