Chasing the Dream: Sorting Fact and Myth Is Biggest Obstacle to Immigration Reform

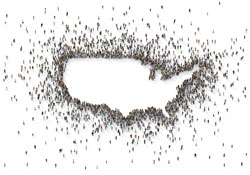

Illustrations by Bryan Christie Design

Consensus doesn’t seem to have a place in policy discussions about the state of the U.S. immigration system. But there is, at least, widespread agreement that the system needs fixing.

“Everyone will tell you the laws aren’t working,” says Brittney Nystrom, director of policy and legal affairs at the National Immigration Forum in Washington, D.C. But beyond that starting premise, views on immigration laws start to splinter.

“On both sides of this debate, there are deeply held beliefs about what immigration means to America,” says Nystrom. “On one side, you have the idea that we’re a nation of immigrants, and it’s healthy and important to keep that tradition alive. On the other side, you have the argument that immigrants are a burden. Trying to factually discuss immigration becomes almost impossible when people tend to fall into one camp or the other based on what they’re told.”

Such an environment is the perfect incubator for rampant mythmaking. Advocates on different sides of the debate support their positions by insisting that certain beliefs must be true while dismissing evidence that might suggest otherwise.

“These myths are largely standing in the way of understanding what’s wrong with our immigration system and how it can be fixed,” says Crystal L. Williams, executive director of the American Immigration Lawyers Association in Washington, D.C.

This pattern isn’t exclusive to immigration law by any means, but certain factors help to make the debate over immigration policy susceptible to myths.

For one, the topic triggers strong emotions in a nation that professes to cherish its immigrant heritage. Even basic terminology is the subject of intense debate. Advocates of more permissive immigration policies prefer neutral-sounding terms like “immigrant” or “undocumented worker,” while proponents of stricter policies maintain that such terms are missing a crucial adjective.

“Illegal alien” and “illegal immigrant” are more accurate terms to describe people who are living in the United States without permission of the law, says Jordan Sekulow, executive director of the American Center for Law and Justice, a conservative Christian advocacy group in Washington, D.C. “These people have violated the law and know they’ve done something wrong,” he says. “Aliens are people here in the United States who aren’t citizens, and it could include tourists here legally. Just calling people ‘aliens’ and ‘immigrants’ isn’t fair to aliens and immigrants here legally.”

It doesn’t help that immigration policy is a hot-button political issue, especially as this presidential election year heats up. “Every politician thinks he can get ahead with an anti-immigration sound bite,” says Karyn S. Schiller, who operates immigration law offices in New York City and White Plains. “There’s nothing to be gained by sounding pro-immigrant. The real loser is the American people because all the positive ways in which the country could benefit from immigration aren’t being explained.”

Complicating the debate is the fact that the immigration system is largely incomprehensible to all but those immersed in it. Americans feel very strongly about immigration, says Michele Waslin, senior policy analyst at the Immigration Policy Center, the research and policy arm of the American Immigration Council in Washington, D.C., “but in reality, few people understand how the system works or what’s wrong with it.”

A byproduct of the serious debate over immigration policy is the proliferation of lists seeking to identify “myths” from the point of the beholders. The council, for instance, has posted on its website Top 10 Myths About Immigration, put together by Justice for Immigrants, a D.C. nonprofit under the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops; and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce published a pamphlet titled Immigration Myths and Facts.

“There’s an old saying in Washington that anyone can find a study that says anything,” says Randy Johnson, senior vice president of labor, immigration and employee benefits at the Washington, D.C.-based chamber. The organization supports targeted legalization of some illegal immigrants and expanded temporary worker programs, along with stricter employer verification procedures and tougher border security.

“We think the weight of the studies is in support of the positions we take,” Johnson says. “Often, when it comes to immigration, those with restrictionist views rely on the minority of the studies on these issues. Also, many studies in this area are done by left-wing groups, and we thought a study by the business community would be given more weight by Republicans in Congress.”

Can the facts about immigration law and policy be easily sorted from the myths? Not necessarily, but in this article the ABA Journal identifies the underlying immigration issues and—relying on documented sources and those with practical and expert knowledge—attempts to pair those issues with factual perspectives.

ISSUE: THE LEGAL IMMIGRATION PROCESS IS FRAUGHT WITH OBSTACLES

The argument that illegal immigrants should just get in line and wait their turn to be allowed to stay in the United States as legal residents sounds reasonable and fair, acknowledge advocates for expanded immigrant rights.

But there is a major flaw in that argument, says Williams of the American Immigration Lawyers Association: “The fact is that 99.9 percent of the people who come here illegally do so because there’s no path for them to come here legally.”

Most noncitizens are required by law to obtain a visa from the U.S. Department of State before traveling to the United States. Visas are issued for specified time periods and subject to certain conditions, depending on the reason for entering this country. Once here, Williams says, noncitizens may pursue either temporary or permanent residency in one of three ways.

The first is on humanitarian grounds, such as asylum seekers who have faced or will face persecution in their home country. “That’s a very high bar,” she notes. The number of cases in which individuals requested asylum dropped by just over 29 percent between the federal years 2007 and 2011, according to the latest statistical yearbook prepared by the Executive Office for Immigration Review in the U.S. Department of Justice. The number of asylum cases completed fell by 27 percent during the same period.

The second option is having a family member who is a U.S. citizen petition for you. “Most don’t have that,” Williams says. “If they do, there’s such a small quota for the category that literally it’ll be 10 to 20 years to reach the front of the line.”

Option three: Have an employer sponsor you. “There’s a very limited quota and a very limited means by which an employer can sponsor you,” says Williams. “An employer must show a shortage of people who can fill that job in the United States, and the quotas are so low for some categories.”

For an unskilled job—anything that requires less than two years of training or experience, which covers most jobs held by those living in the country without legal permission—the annual quota is 5,000, including family members, Williams says. “So really the quota is 2,000 to 3,000 people,” she says. “It’s expensive, and the backlog is so long that most employers won’t pursue it.”

The bottom line: “If you’re coming here to build a better life for your family, there’s really no way to come here legally,” Williams says. “Why don’t they just get in line? There’s no line to get into.”

ISSUE: IMMIGRANTS BECOMING CITIZENS THROUGH MARRIAGE

Marrying a U.S. citizen is a common path to permanent residency and perhaps eventual citizenship for foreign nationals, but it’s not a guarantee, says Susan Schreiber, the managing attorney for training and legal support at the Catholic Legal Immigration Network in Chicago.

“Marriage gets you married—that’s the only thing it automatically does,” Schreiber says. “It’s a possible and common route to residency. But it has to be initiated by a U.S. citizen, and there’s no obligation for any person to petition for citizenship for another. Even then, there are many requirements. The relationship status isn’t enough.”

The restrictions can be challenging. “If you marry a U.S. citizen,” Williams says, “and have any criminal background or are likely to become a public charge—in other words, if you’re poor and your spouse is poor as well—you can’t get a green card,” which grants permanent residence. And, says Williams, “if the government suspects the marriage isn’t real, it can deny the application.”

Immigration lawyer Schiller is familiar with the citizenship-through-marriage process from firsthand experience. She was born in South Africa and immigrated to the United States in 1990 after marrying a citizen. “I had to go through the same process anybody does who marries a U.S. citizen, but back then it wasn’t as rigorous,” she says. Now, there is almost a presumption of marriage fraud, she says. “I’ve been married for 25 years, and some times when I’m with my clients in marriage-based interviews, I wouldn’t be able to answer the questions they’re asked: ‘What brand is the TV set in your living room?’ I wouldn’t know that. ‘How many times a week does your husband speak to his mother?’ I don’t know that.”

There’s one big, final caveat. If a noncitizen enters the country without inspection—known in the field as EWI—marriage is precluded as an avenue to permanent residency or citizenship.

“When you come to the United States as a tourist, you’re inspected,” Schiller says. “If you jump the border, as many aliens do, many of the benefits otherwise available aren’t available. The consequences are incredibly harsh, and people who’ve done that are in very dire circumstances vis-à-vis immigration.

“So if you marry a U.S. citizen in a genuine marriage, yet you entered EWI, you’re prohibited from getting a green card.”

It’s possible to apply for a waiver, but they’re rarely granted, Schiller says. In addition, the applicant must leave the United States and will be barred from re-entry for as many as 10 years depending on how long he or she was living here without documentation.

ISSUE: PARENTS GAINING CITIZENSHIP THROUGH CHILDREN

In 2009, some 350,000 children were born in the United States with at least one parent in this country illegally, according to a report issued by the Pew Hispanic Center in D.C. These children are sometimes called “anchor babies” in reference to federal laws that allow them to automatically become U.S. citizens and sponsor parents for citizenship, as well.

That interpretation of the law is largely accurate, but it’s subject to a critical limitation. “A child can’t file an action for citizenship for parents until the child has turned 21,” Sekulow says. “But children can do it then, and the parents will be on track for citizenship unless they have other problems that prevent citizenship from being granted.”

That’s a long time for a parent to wait to achieve legal status, says Schiller. And having a child who is a U.S. citizen doesn’t mean a parent won’t be derailed from achieving legal status on other grounds. “People are deported every single day with U.S. citizen children,” she observes. “In addition, if you’re EWI, even your child can’t sponsor you.”

ISSUE: ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS RECEIVING PUBLIC BENEFITS

“Although the United States’ welfare rolls are already swollen, every year we import more people who wind up on public assistance: immigrants,” says the Washington, D.C.-based Federation for American Immigration Reform in a statement posted on its website. “As a result of their high rate of poverty, immigrant households are more likely to participate in practically every one of the major means-tested programs.”

Citing a report published by the Center for Immigration Studies, FAIR says that in 2007, immigrant use of welfare programs was 69 percent higher than use by nonimmigrants.

Some other groups take issue with that contention. Among them is the Chamber of Commerce, which lists access to benefits as one of its immigration myths. “Undocumented immigrants are not eligible for federal public benefits such as Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Medicaid, Medicare and food stamps,” states the chamber in its Immigration Myths and Facts. “Even most legal immigrants cannot receive these benefits until they have been in the United States for five years or longer, regardless of how much they have worked or paid taxes.”

But there are at least two government programs available to illegal immigrants. “They get emergency medical care and, under Plyler v. Doe, children are eligible for public schooling through high school,” says Donald M. Kerwin Jr., the executive director of the Center for Migration Studies in New York City and a member of the ABA’s immigration commission.

“A lot of those costs are borne by local communities, and that’s one of the anomalies that does need to be addressed,” Kerwin says. “The federal government benefits from taxes on aliens. But states and localities bear the cost of educating the children and providing basic health services.”

Immigrants become eligible for Social Security benefits when they become permanent residents, but in many cases they actually are helping the system even as illegal residents, says Kathleen Camp bell Walker, a shareholder at Cox Smith Matthews in El Paso, Texas, and a past president of the American Immigration Lawyers Association. “Our Social Security fund has millions in it from people who’ve used a fake Social Security card to get work, and there’s nowhere that money’s going to go,” she says. “It’s been helping prop up our cratering Social Security system for years, and a lot of that’s due to undocumented workers.”

ISSUE: ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS GETTING THEIR DAY IN COURT

During fiscal year 2011, federal immigration courts completed 303,287 cases involving removal, deportation, asylum or other proceedings that decided whether illegal immigrants could stay in the U.S., according to the statistical yearbook prepared by the Executive Office for Immigration Review. That represents an increase of 29,807, or nearly 11 percent, over the number of cases completed in fiscal 2007.

So it’s clear that, as some proponents of tougher immigration laws maintain, many unauthorized immigrants at least get to make their case in court before a decision on their status is rendered.

But thousands of illegal immigrants are removed from the United States without appearing before a judge in a full removal hearing. “The majority of people who are removed never see the inside of a court,” says Kerwin of the Center for Migration Studies. “That’s something that should be of significant concern to the organized bar.”

Many lawyers also would be surprised by the lack of legal protections available to immigrants during the removal process, says Nystrom from the National Immigration Forum. “Most of us lawyers by training assume that for a consequence as severe as deportation, there must have been some robust process and a chance for representation and adjudication somewhere along the way,” she says.

“However, it comes as a surprise,” Nystrom says, “to those who assume there’s something akin to rights in the criminal system when they realize many people are mandatorily detained and deported because of criminal laws, or because they signed documents they didn’t understand but turned out to be a stipulated order of removal.”

Then there’s expedited removal, which allows U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers to deny entry to noncitizens. In 2010, expedited removals accounted for 111,000—or 29 percent—of all removals, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

The expedited removal process is arbitrary, unfair and unconstitutional, Walker argues. “If one of our officers decides I’ve lied to him about my status or he thinks I’m coming to remain permanently rather than just visiting, he can subject me to expedited removal,” she says.“I don’t get to make a phone call to legal counsel, and I have no right to a hearing before any kind of judge. Maybe the person had a valid asylum claim and was fleeing a dangerous situation.

“The process gives those officers incredible power over your life and can subject you to a position that’s horrific,” Walker says. “It’s permitted because of expediency and the cost of the resources it takes to provide due process. The truths that we hold self-evident should be blind to your immigration status.”

ISSUE: LEGAL REPRESENTATION FOR IMMIGRANTS IN REMOVAL PROCEEDINGS

The Justice Department says that 2011 was the first time more than half of immigrants whose removal proceedings were completed had lawyers. And, as always, they had to cover the cost out of their own pockets.

The FY 2011 Statistical Year Book (PDF) published by the department’s Executive Office for Immigration Review estimates that 51 percent of the individuals in completed proceedings were represented by counsel. That’s the highest rate of representation since 2006, when only 35 percent of individuals involved in completed proceedings had counsel. But it still leaves a lot of people to fend for themselves.

“Even among people who do make it to immigration court—and that’s a small subset of immigrants—their only right is to hire their own lawyer,” says Ira Azulay, a member of Immigration Attorneys in Chicago. “There’s no public aid for aliens, and there’s no guaranteed right to a lawyer.”

The ABA’s policymaking House of Delegates approved a resolution urging federal, state, territorial, tribal and local governments to provide funding to state and federal public defender offices—as well as legal aid programs—and to give advice about immigration issues to indigent non-U.S. citizen defendants. At the same meeting, the House adopted the ABA Model Access Act pursuant to policy adopted in 2006 calling on federal, state and territorial governments to provide low-income individuals with state-funded counsel when basic human needs are at stake.

At least one study suggests what impact legal representation would have in immigration proceedings. In 2005, a study by the Migration Policy Institute found that 41 percent of detainees who had legal counsel in their applications to become lawful permanent residents won their cases; 21 percent of those without representation were successful. In asylum cases, 18 percent of detainees with legal representation were granted asylum, while only 3 percent of unrepresented detainees were successful.

ISSUE: ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS DON’T PAY THEIR FAIR SHARE OF TAXES

The Federation for American Immigration Reform issued a report titled The Fiscal Burden of Illegal Immigration on United States Taxpayers (PDF), first published in 2010 and updated last year. The FAIR report estimates that illegal immigrants cost U.S. taxpayers some $113 billion a year, with most of that—about $84 billion—being absorbed by state and local governments. At the federal level, according to FAIR, only about a third of those payouts are offset by tax collections from illegal immigrants, and less than 5 percent of the public costs of illegal immigration at the state and local levels are recouped through taxes paid by illegal immigrants.

Using the findings to make a case against the kind of broad amnesty for unauthorized immigrants that last occurred in 1986, FAIR states in the report that while tax collections from illegal immigrants would likely increase only marginally, their new legal status would make them eligible for Social Security benefits and social assistance programs for which they don’t currently qualify. The overall result of an amnesty “would, therefore, be an accentuation of the already enormous fiscal burden” facing governments at all levels, the report states.

The Chamber of Commerce takes a different position on the tax issue. “Undocumented immigrants pay sales taxes, just like every other consumer in the United States,” states the chamber’s Immigration Myths and Facts pamphlet. “More than half of undocumented immigrants provide their employers with counterfeit identity documents, so federal and state income taxes, Social Security taxes and Medicare taxes are automatically deducted from their paychecks. Tax payments by undocumented immigrants and their families are also sizable at the state and local level.”

The chamber cites estimates from the Social Security Administration that, through October 2009, illegal immigrants using false documents reported some $836 billion in wages eligible for Social Security tax withholding.

The tax issue is more nuanced than many people realize, says Sekulow of the American Center for Law and Justice. “It’s not true that people don’t pay taxes if you’re talking about people with green cards or people here illegally using fake documentation,” he says. “Of course they’re paying taxes if they’re working regular jobs and their employer is withholding taxes. If you’re talking about day laborers, they’re typically not paying taxes. But that still doesn’t mean that people who may have a Social Security number are fully contributing to the tax system the way a legal worker might be. It’s a multi-tiered issue.”

New York attorney Schiller says most of her clients don’t want to take the risk of not filing income tax returns. “Undocumented aliens are very aware of things that will prevent them from getting a green card,” she says. “They know not paying taxes will be a bar. You’ll be deemed to have what’s called bad moral character. In my practice, 99 percent of undocumented individuals pay their taxes by getting a taxpayer identification number in the hope that maybe one day they’ll get a green card. Many of them don’t and end up going back after years and years paying taxes and not getting anything in return.”

ISSUE: ILLEGAL IMMIGRANTS TAKING JOBS FROM AMERICAN WORKERS

This is the first issue the U.S. Chamber of Commerce addresses in its list of immigration myths and facts.

“The U.S. economy does not contain some fixed number of jobs for which immigrants and native-born workers compete,” states the chamber. “For instance, if the approximately 8 million unauthorized immigrants currently working in the United States were removed from the country, there would not be 8 million job openings for unemployed Americans. Why? Because native-born workers and immigrant workers possess different skills and cannot simply be swapped for one another like batteries. And because removing 8 million undocumented workers from the economy also means removing 8 million consumers—and the jobs they support through their spending.”

A tough new immigration law that went into effect in Georgia on July 1, 2011, had a noticeably detrimental effect on the state’s agricultural industry. In June, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that Georgia farmers faced big losses because illegal immigrants were afraid to work in the state. Gov. Nathan Deal proposed that convicts on probation be encouraged to replace the absent immigrant workers, but Politico reported on June 22 that “some of the convicted criminals started walking off their jobs because field work was too strenuous.”

In a University of Georgia survey released in October, farmers reported 40 percent fewer workers than in previous years. The survey estimated crop losses of at least $70 million for Georgia fruit and vegetable farmers; losses grew to $390 million when estimating the total economic impact from fewer farmworkers living and spending money in Georgia. State farmers and other business leaders and lawmakers have debated the wisdom of the law, but efforts to amend it haven’t gotten off the ground.

ISSUE: IMMIGRANTS ASSIMILATING INTO AMERICAN SOCIETY

The argument goes essentially like this: In the old days (a date uncertain), immigrants arrived in the United States anxious to learn the language of their new homeland and assimilate quickly into American culture. Their ultimate goal was U.S. citizenship, and they followed the rules in efforts to gain that cherished status. Today’s immigrants—legal or illegal—just don’t share that same commitment to American culture or citizenship.

Waslin from the Immigration Policy Center says this scenario fails to account for changes in U.S. immigration laws over the years.

“When most of our parents and grandparents came to the United States, the laws were very different,” she says. “Not only were more people eligible because the rules were less strict, but a lot of people forget that a lot of them didn’t come legally. There have been amnesty or legalization programs a lot of our ancestors benefited from.”

Gregory Siskind, a founding member of immigration firm Siskind Susser in Memphis, Tenn., hates (his word) the argument that immigrants don’t want to assimilate. “In the early 1900s, it was an almost completely open immigration system,” he says. “The hardest part of coming into Ellis Island was affording a ticket. All you had to do was list on the ship form that you had someone you were meeting in the United States and have a little money in your pocket.”

Siskind also maintains that opposition to immigration has a long tradition in the U.S. “Pick up a newspaper from 100 years ago,” he says. “You think anti-immigration groups are active today? They were much more incensed then about all the Yiddish and Italian languages they heard. There’s nothing new about what we’re arguing today.”

In Top 10 Myths About Immigration, the American Immigration Council takes a long-range perspective: “If we view history objectively, we remember that every new wave of immigrants has been met with suspicion and doubt; and yet, ultimately, every past wave of immigrants has been vindicated and saluted.”

G.M. Filisko is a lawyer and freelance journalist in Chicago.