Coronavirus-related deaths in nursing homes prompt lawsuits and questions about who's responsible

Carol Orlando, left, and her daughter, Faith Heimbrodt. Photo courtesy of the Orlando family.

In mid-April, Faith Heimbrodt got a call from the Bria Health Services nursing home in Geneva, Illinois, saying her mother, Carol Orlando, was not in good health. She immediately feared COVID-19. But she says facility staff insisted her 79-year-old mother didn’t show symptoms of the virus, and that her illness likely was due to her advanced dementia.

Alarmed, she got permission to visit her mother, even though the facility had been on lockdown since March. Heimbrodt, who has five children at home and suffers from multiple sclerosis, went wearing a gown, respirator and face shield, but she was shocked to see staff and residents without masks. A desperate-looking certified nursing assistant asked how she got her respirator, so she gave it to him.

Her mother’s room was filthy, with dirty diapers on the floor. Her roommate was coughing, unmasked, in the adjoining bed, with no room divider. Orlando looked thin and dehydrated, her eyes sunken and her mouth covered with sores. Heimbrodt squeezed her mother’s hand and leaned in close, wanting but not daring to lift her face shield and kiss her. She left sooner than she planned, nervous about the risk of exposure to the virus.

A week later, Heimbrodt got a call that her mother was dead. She arranged for a private autopsy, but the company called back to say they couldn’t do it because Orlando’s body bag was labeled “COVID.” She found out a nursing home staffer had written that on the bag because she believed Orlando had the virus—even though the facility never tested her and denied she had it.

Orlando, whom the local coroner later determined had the virus, was one of many Bria residents who died from COVID-19. As of early September, the state of Illinois reported 136 Bria residents and staff members had tested positive for COVID-19, and 30 people there had died from it.

In early June, the Chicago law firm Levin & Perconti filed a lawsuit against Bria on Heimbrodt’s behalf, claiming the facility was grossly negligent and engaged in willful and wanton conduct by failing to take the necessary steps to protect Orlando from the virus and provide adequate care once she got it.

The suit, filed in Kane County Circuit Court, alleges Bria did not have enough staff to adequately care for residents and failed to have staff wear personal protective equipment or undergo COVID-19 tests to prevent virus transmission to residents. It cites both the Illinois Nursing Home Care Act and common law tort theories.

“I think about my mother dying alone,” Heimbrodt says, noting Orlando had trained to become a CNA in middle age because of the poor care her own mother had received in a nursing home. “I hope my lawsuit and others will hold these nursing homes accountable.”

Natalie Bauer Luce, a Bria spokeswoman, says Heimbrodt’s statements to the ABA Journal about the conditions at Bria and the allegations in her lawsuit are unfounded. Luce says lawsuits like this one “send a dangerous message … to the health care heroes on the front lines that their efforts to save lives will be used against them by personal injury lawyers seeking to profit by taking advantage of the global pandemic.”

Funeral director Joe Ruggiero III moves a casket into a makeshift storage room at Ruggiero Family Memorial Home in East Boston in April. Jessica Rinaldi/Boston Globe via Getty Images.

Suits piling up nationally

Heimbrodt’s case is one of a growing number of negligence suits being filed across the country against nursing homes and other long-term care facilities by families whose relatives died from the coronavirus while living in such facilities. These cases rely on state nursing home resident protection statutes and/or common law tort theories.

There’s no comprehensive database of case filings. But a COVID-19 complaint tracker posted on the website of the law firm Hunton Andrews Kurth shows 55 wrongful death lawsuits filed against long-term care facilities around the country as of early September. More suits are on the way, with plaintiffs attorneys in Florida, Massachusetts and other states that have mandatory presuit screening periods saying they are investigating and preparing to file cases.

Whether it’s a flood or a moderate flow, these cases will present unprecedented questions for judges, juries and arbitrators. They will have to decide whether and how to apportion responsibility for the deaths of the nation’s most medically vulnerable population among long-term care operators who were scrambling in the midst of the chaos and confusion during the worst public health emergency in a century.

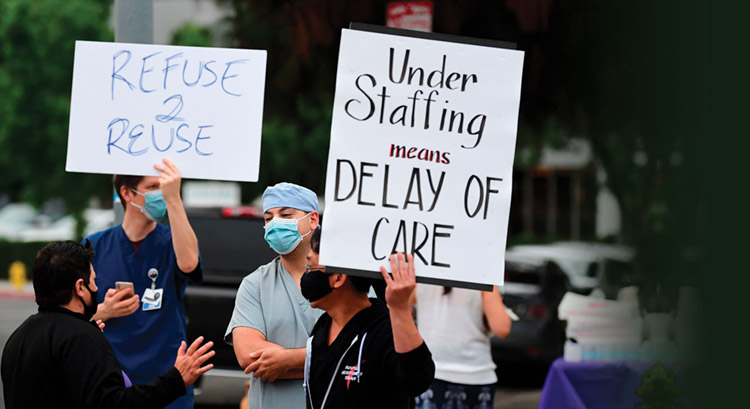

Nurses staged a protest in June in West Hills, California, with support from the local registered nurses’ union. The nurses were demanding an end to “critically” low staffing, insufficient personal protective equipment, silencing of whistleblowers and a lack of transparency in the wake of cuts made during the coronavirus pandemic. Photo by Frederic J. Brown/AFP via Getty Images.

“It will be really interesting to see how well the courts are able to balance the nuances of who’s really to blame at a facility when, nationally, we didn’t have a lot of information about the virus, and there weren’t a lot of resources,” says David Grabowski, a health care policy professor at Harvard Medical School who studies long-term care. “That’s not to say there aren’t bad apples that deserve to be held accountable.”

More than 51,000 of the nation’s 1.4 million nursing home residents, who generally are elderly and/or disabled, have died of COVID-19 since the beginning of this year, accounting for a large share of the more than 188,000 COVID-19 deaths in the United States as of early September, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation and a New York Times database.

Over 750 nursing home employees spread across the 15,000 federally certified nursing homes also have died from the virus, and plaintiffs lawyers say they’re getting requests from their families to explore lawsuits. But those cases generally must be handled through state workers’ compensation systems, which tightly cap death benefits.

In most cases filed so far on behalf of residents, the plaintiffs say nursing home staff did not disclose timely truthful information to them about COVID-19 cases in the facility, infection control procedures, and the health status and care of their relatives before they died. Many still haven’t been able to obtain their relatives’ medical records even months after their deaths. A lawsuit is the only way to piece together the stories, their attorneys say.

But plaintiffs and their attorneys face formidable obstacles in bringing these cases. At least 26 states, including Illinois, Michigan, New Jersey and New York, have implemented immunity provisions protecting long-term care facilities and other health care providers from civil negligence lawsuits arising from the COVID-19 pandemic—including decisions resulting from resource or staffing shortages. They provide immunity for acts or omissions that happened after state public emergency orders were issued in March, but not before.

Those measures generally bar claims for standard negligence, only allowing claims for harder-to-prove gross negligence, willful misconduct or fraud. Gross negligence typically requires demonstrating deliberate or reckless disregard for a resident’s health and safety, which is a higher standard than simply showing the facility did not follow the common standard of care.

Anna Epstein and her daughter, Ridley, say good-bye to Anna’s mother, Donna Forsman, after chatting via cellphone during a through-the-door visit at Brookdale Arlington Senior Living in Arlington, Virginia, in March. Photo by Jahi Chikwendiu/Washington Post via Getty Images.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., is pushing for broad immunity provisions covering all states, though the fate of that proposal is uncertain because Democrats are strongly opposed.

The Safe to Work Act, sponsored by Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, would give nursing homes and other businesses five years of legal protection if they make “reasonable efforts” to comply with government standards to protect residents, staff and others from the coronavirus. It would allow any defendant to remove a COVID-19 exposure lawsuit to federal court. Lawsuits would be limited to allegations of gross negligence or willful misconduct, which could not include acts or omissions resulting from resource or staffing shortages.

Steven Levin, who’s bringing the Carol Orlando case, says he will overcome the immunity barrier in Illinois and other states by initially proceeding against “the worst actors, with a poor regulatory history and no infection-control procedures in place, that didn’t tell the truth to families and forced employees to come to work when they were sick with COVID-19.”

Beyond that, plaintiffs attorneys acknowledge it will be challenging to prove that a nursing home’s conduct, such as failure to establish proper infection control procedures like masking of staff and isolation of residents testing positive for COVID-19, directly caused a resident to become infected and die.

“These won’t be easy suits,” says Levin, whose firm has received requests from more than 100 families to explore litigation. “The nursing home might say, ‘A family member brought the virus into the facility, and it spread like wildfire. How could anyone have done anything?’ We’ll show they could have done things to be better prepared.”

Defense attorneys will plausibly argue that good-faith efforts by nursing homes were hampered by delayed or faulty policy guidance from state and federal agencies and by the nationwide shortage of personal protection equipment and coronavirus test kits. The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services didn’t order nursing homes to restrict visitors and communal activities until March 13. The timeline of events in these cases will be key.

Medical staff in full personal protective equipment take a breather while helping to remove patients from Magnolia Rehabilitation and Nursing Center in Riverside, California, in April, after 39 patients and staff tested positive for the coronavirus. Nursing staff was not showing up to work for their own safety. Photo by Gina Ferazzi / Contributor /Los Angeles Times via Getty Images.

“Nursing home administrators were screaming for PPE, and they weren’t getting it,” says Kelly Giampa, an attorney at Lindsay Hart in Portland, Oregon, who represents Healthcare at Foster Creek, which has been sued by six families over COVID-19 deaths. “The cases will be very fact-specific. What was the availability of PPE, and what efforts were made to get it?”

Plus, many or most of these cases ultimately will be handled through arbitration because nursing homes increasingly require residents and their families to sign mandatory arbitration agreements. Plaintiffs attorneys sometimes can nullify such agreements by, for instance, showing that the relative who signed lacked power of attorney for the resident. But they say they’d much rather take these cases to juries.

Some of the facilities with the largest COVID-19 outbreaks and death totals already have been hit with lawsuits. They include Healthcare at Foster Creek, which was shut down by the state in early May and had 34 of its residents die from the virus; Hollywood Premier Healthcare Center in Los Angeles, where at least 16 residents died from the virus and the National Guard was deployed to help with the crisis; and the Linden Center for Nursing and Rehabilitation in Brooklyn, New York, where an estimated 23 residents died from COVID-19 and where dead bodies were held for days in “overflow rooms” cooled only by air conditioners.

The complaints in these and other cases sometimes stress the facilities’ extensive histories of violations of state and federal health and safety rules. That will be a battleground, because courts often rule that such evidence is irrelevant and inadmissible, says Linda Clark, a partner at Barclay Damon in Albany, New York.

Plaintiffs attorneys will press hard to admit evidence of a facility’s prior troubled history to show it was a “ticking time bomb,” strengthening their gross negligence claim, says plaintiffs attorney David Hoey of Hoey Law in North Reading, Massachusetts, where the governor signed an immunity order allowing only claims of gross negligence.

The nursing home industry says that without strong immunity measures in every state, the number of lawsuits will threaten the industry’s survival.

“More needs to be done to afford appropriate legal protection to those that are working hard to prevent and contain this virus,” says Mark Parkinson, president and CEO of the American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living. “We encourage states and the federal government to take action to extend immunity provisions to the long-term care providers and other health care sectors.

“Long-term care workers and centers are on the front line of this pandemic response, and it is critical that states provide the necessary liability protection staff, and providers need to provide care during this difficult time without fear of reprisal,” he adds.

Attorneys experienced in bringing nursing home cases predict only the worst offenders will be targeted.

Kathy Johnson visits her husband, Michael Johnson, at the North Ridge Health and Rehab nursing home in New Hope, Minnesota. Photo by Richard Tsong-Taatarii/Star Tribune via Getty Images.

Who’s to blame?

Up until now, most nursing home liability cases have focused on common though potentially fatal lapses in care such as failure to prevent falls or pressure sores. These cases are based on negligence law and state nursing home resident protection statutes modeled on the federal Nursing Home Reform Act of 1987. They sometimes yield seven-figure awards, with punitive damages permitted in some states. Some states cap noneconomic damages.

In most cases, family members visiting relatives are the ones who identify care problems. But with nursing homes closed to visitors since March, there’s no one other than facility staff regularly monitoring residents’ care. That has led to a steep drop-off in the usual types of nursing home negligence claims, plaintiffs attorneys say.

“Because the residents’ kids can’t enter the facilities, those injuries aren’t being reported, and that’s deeply disturbing,” says Michael Brevda, a partner at the Senior Justice Law Firm in Boca Raton, Florida.

Thus, plaintiffs will have to rely, to an unusual extent, on medical records as well as accounts from current and former nursing home employees, some of whom have been speaking to the news media and plaintiffs attorneys about conditions inside the facilities.

For instance, Alexander Clem, an attorney at Morgan & Morgan in Orlando, Florida, is preparing a case against the Suwannee Health and Rehabilitation Center in Live Oak based in part on information provided by a former CNA at the facility. She has told news media outlets that managers concealed residents’ fevers by putting ice packs on their heads to avoid having to report COVID-19 cases and discouraged staff from getting tested. At least 19 residents have died from the virus.

“When you have a scenario like that where there is substantial evidence that management of a facility took action to cover up incidence of COVID, I don’t think a jury or arbitration panel will ever give them a pass on liability,” says Clem, whose state has not established immunity for nursing homes.

Suwannee did not return a call seeking comment.

Some observers predict that evidence of COVID-19 cover-ups will emerge at other facilities, too. They say such claims, if proved, will rise to the level of willful misconduct and pierce state immunity provisions.

Dr. Michael Wasserman, president of the California Association of Long-Term Care Medicine and medical director at the Eisenberg Village nursing home in Reseda, California, says he’s talked to nursing home physicians and managers who sought to test staff or residents for the virus but were overruled by administrators. One was fired and is planning to sue. “So many of my colleagues wouldn’t go public with their stories of management’s resistance to testing, but I think ultimately these stories will come out in lawsuits,” he says.

Defense attorney Giampa says she’s not worried about what employees say. “In every case, we have staff members who say, ‘We were short-staffed, I complained about this and that,’” she says. “You have to drill down and see how accurate it is.”

Key strategy qualifiers

Even if a facility didn’t engage in a cover-up, the chronology of its actions to prevent or minimize the spread of the virus will be crucial, Clem says.

It’s one thing if a resident contracted COVID-19 in mid-February, after the first nursing home outbreak was suspected in Washington state but the risk of asymptomatic transmission wasn’t widely known. It’s quite different if facility management failed to implement strict measures by mid-March.

“At that point, management damn sure knew this was a crisis of pandemic proportions,” Clem says. “Then, what were you doing to prevent onset of the virus? And once you became aware of a case, what did you do?”

Scott Weinstein, a nurse at Medstar Washington Hospital Center, places nurses’ shoes on the lawn of the U.S. Capitol in Wash-ington, D.C., during a vigil in July for nurses who have died from COVID-19. Photo by Tasos Katopodis/Getty Images.

Plaintiffs attorneys say most of the COVID-19 cases coming to them involve for-profit nursing homes, which they believe are more likely than not-for-profit operators to skimp on staffing to boost profits, and their complex ownership structures make attorney investigations difficult. The nursing home industry blames low Medicaid payment rates and a shortage of willing and qualified direct care workers for the chronic understaffing.

A major theme in the COVID-19 lawsuits filed so far is that families are angry about what they see as a lack of transparency and honesty by nursing homes in the days leading up to their loved one’s death. That’s a big part of a lawsuit filed in mid-May by the Portland firm Richardson Wright against Healthcare at Foster Creek, and amended in June to add five more families of deceased residents as plaintiffs.

Giampa, who’s representing Foster Creek, declined to comment specifically on the Foster Creek lawsuit.

Giampa predicts COVID-19 nursing home liability cases will be unusually tough and emotional, drawing on the intense feelings of judges, jurors and arbitrators about their own experiences during this unprecedented period of national turmoil.

“COVID has impacted everyone, and whether these cases get tried in six months or four years, people on our juries are not going to forget what this time was like,” she says. “They will remember that these caregivers showed up for work, risking infection to themselves and their families, and doing the best they could every day.”

But personal experiences could cut the other way, too. “Jurors will remember all the actions and sacrifices they made in their private lives, wearing masks, staying home and disinfecting food,” Brevda says. “It will enrage them that nursing homes failed to similarly follow infection protocols.”

This story was originally published in the October-November 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “A Question of Neglect? Coronavirus-related deaths in nursing homes seed lawsuits and questions about who’s responsible”

Harris Meyer is a Chicago-based health care and law reporter who has written for Kaiser Health News, Health Affairs, Modern Healthcare, the Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.