Employment picture for law grads looks pretty much the same as a year ago—for better and worse

Illustration by Brenan Sharp

Employment data released in late March by the ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar indicates that 2012 law school graduates face essentially the same job market that greeted the class of 2011.

The data reflects the known employment status of 97.4 percent of the 2012 graduates of U.S. law schools accredited by the section as of mid-February 2013, or nine months after receiving their degrees. The comparative data for 2011 graduates is based on the known employment status of 96.4 percent of that class nine months after receiving their degrees. There are 202 law schools approved by the legal education section, which is recognized by the U.S. Department of Education as the national accrediting body for law schools in this country.

The numbers tell a good news/bad news story from which no clear pattern emerges.

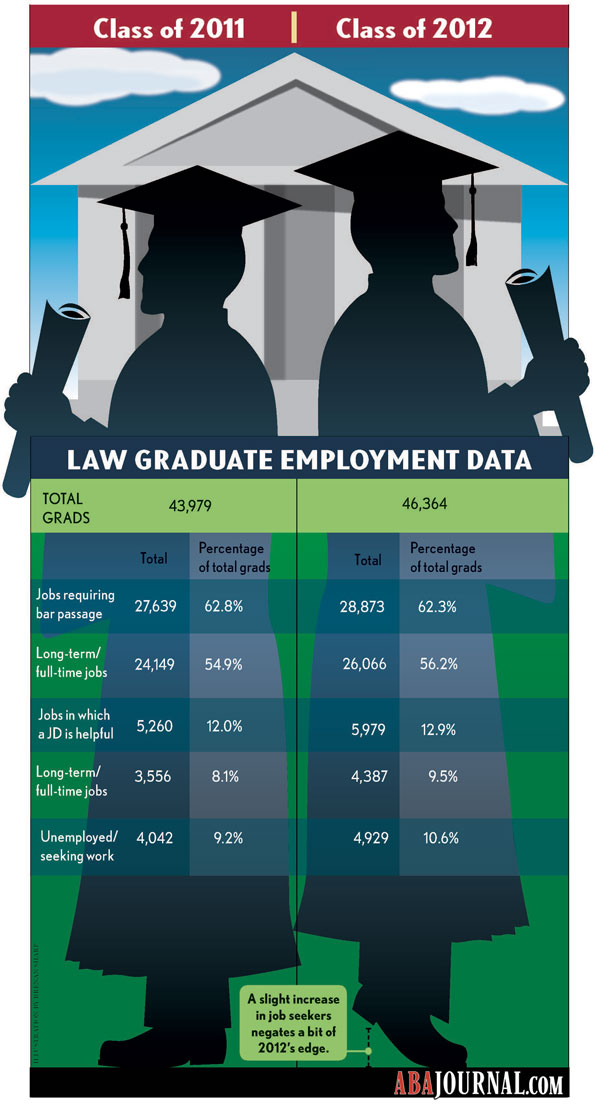

As of Feb. 15, for instance, 56.2 percent of all 2012 graduates of ABA-approved law schools held long-term/full-time jobs—expected to last a year or more—that require a license to practice law. That’s a slight improvement over the previous year, when 54.9 percent of 2011 graduates of ABA-approved schools held full-time/long-term jobs requiring a law license nine months after graduation.

But the segment of graduates holding jobs in four key types of employment status (long term or short term, combined with full time or part time) requiring a law license declined slightly from 62.8 percent of all graduates in 2011 to 62.3 percent for 2012 grads. The actual employment numbers for graduates with a law license increased, however, from 27,639 graduates in 2011 to 28,873 members of the class of 2012, a reflection of the larger total number of graduates in 2012.

Another 12.9 percent of 2012 graduates were employed as of Feb. 15 in jobs for which a law degree is preferred but not required, according to the data, which is a slight improvement over 2011, when 12 percent of graduates of ABA-approved law schools held “JD advantage” positions.

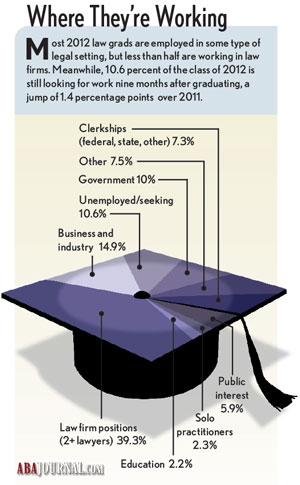

But the percentage of 2012 graduates who still were unemployed and seeking work nine months later—10.6 percent—reflects an increase from 2011, when 9.2 percent of all graduates were unemployed and seeking work nine months later.

Source: ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. Illustration by Brenan Sharp.

SPIKE OR TREND?

The single biggest change for the class of 2012 is its size. At 46,364 graduates, the class was the largest on record, 5.4 percent more than the 43,979 graduates of ABA-approved law schools in 2011. That increase may turn out to be a spike rather than a trend, however, in light of a 38 percent drop in law school applications since 2010 that has been reported by the Law School Admission Council. Admissions dropped 7.7 percent from fall 2010 to fall 2011, according to the council’s website. Numbers for 2012 were not posted.

Barry Currier, the legal education section’s newly appointed managing director of accreditation and legal education, declined to offer an interpretation of what the numbers mean. “Our job is to get the data out there as quickly and as accurately as possible,” he says. “I’ll leave it to others to comment on whether the numbers are good or bad.”

Kyle McEntee of Atlanta, executive director and co-founder of the law school reform group Law School Transparency, says the data shows how difficult the job market remains for law school graduates.

Excluding jobs funded by law schools, he says, only 55.1 percent of all 2012 graduates were employed in full-time, long-term lawyer jobs nine months later, 1.1 percentage points lower than the 56.2 percent figure cited by the section. McEntee also says the data shows that a “devastating” 27.7 percent of all 2012 graduates were either unemployed or pursuing an additional degree, or underemployed, meaning they were working in short-term, part-time or non-professional jobs.

Given those realities, McEntee urged prospective students to exercise caution. “Law school is too expensive relative to job outcomes,” he says. “If you plan to debt-finance your education or use hard-earned savings, seriously think twice about attending a law school without a steep discount. For the vast majority of prospective law students who have not received a sizable scholarship, it makes sense to wait for prices to drop.”

Sidebar

Edging Ahead

Nine months after graduating, members of the U.S. law school class of 2012 are doing better than their colleagues in the class of 2011—but just barely. The number of 2012 grads working full time in a job that requires a law license and is likely to last at least a year increased by 1.3 percentage points over 2011. The number of 2012 grads holding long-term/full-time positions for which a law license is preferred but not required increased by 1.4 percentage points. Meanwhile, 10.6 percent of the class of 2012 was still unemployed and looking for work nine months after graduation—an increase of 1.4 percentage points over the class of 2011. Those numbers are unlikely to trigger happy thoughts among members of the nation’s law school class of 2013.

Source: ABA Section of Legal Education and Admissions to the Bar. Illustration by Brenan Sharp.