Ending mass incarceration won’t succeed without giving people a second chance

Photo by Wayne Slezak

As he rode the bus home to Chicago from the Vienna Correctional Center in downstate Illinois, Steve Price told himself that he wasn’t going back. At age 32, he’d already been to prison six times. He’d had enough. This time was going to be different.

This time, Price felt better prepared for re-entry. During his stints behind bars, he learned how to read. He earned a high school equivalency diploma. He trained to be a barber and passed the state licensing exam.

His mom, Eula, met Price at the bus station downtown and drove him to their home on the South Side where she cooked dinner. “I told her, I don’t think I’m going back to jail again,” Price recalls. “And all she would say was that time will tell.”

Her skepticism was well-placed. Price had a rap sheet that began at age 13, around the time he started running with a street gang. As an adult, his convictions were for nonviolent crimes—burglary, retail theft and drug possession. He was a heroin addict, and he stole to support his habit.

Once back home, Price checked in with his parole officer and went looking for a job. “As soon as they found out about my background it was like, ‘No, we can’t hire you,’ ” he says. He talked his way into cutting hair at a couple of barber shops, but he was unable to land a permanent gig.

He began to feel desperate. “I knew I wanted to change, but I didn’t know how. I didn’t know where to go, what to do, anything like that,” Price says. “The parole officers didn’t have any information for us. They were overloaded, and they would just come to see me, and that was it.”

Frustrated and depressed, Price hit the streets, looking to score drugs. “I was still really angry about a lot of stuff,” he says. “I wasn’t ready. I focused on getting high.”

He began stealing again, and before long, Price was back in prison. The year was 1996.

A Revolving Door

Such stories are common. People like Steve Price—poor, African-American, a high school dropout, raised by a single mom, forced to hustle on the street to survive—fall into a pattern. They get arrested, go to prison and are released with little or no preparation, counseling or drug treatment. Most have no job skills, and few employers are willing to hire them because they have a criminal record. So they wind up going back. Recidivism is a problem that for decades has continued to spin the revolving door of mass incarceration.

While the United States has consistently put more people in prison than any other country, it has come up short in helping rebuild their lives once they’re released. More than 600,000 people leave the nation’s prisons every year with little more than a bus ticket and 50 bucks. Within five years, more than half of former state inmates are back inside.

THE ‘DECARCERATED’

While there’s been a growing bipartisan movement to end mass incarceration, such efforts still must grapple with the increasing number of “decarcerated” individuals. The national First Step Act, a major criminal justice reform initiative signed by President Donald Trump in December, offers some hope. It includes reforms that reduce sentences for federal drug crimes and funding for programs to reduce recidivism. The president in April announced plans for a “Second Step Act” in his fiscal 2020 budget that will focus on re-entry and reducing unemployment for this with criminal records. But these programs apply only to those convicted of federal crimes. Most incarcerated people are in state prisons and county jails. To complicate matters, state and local governments have thousands of laws, regulations and policies that create barriers that even the most determined people have trouble scaling when trying to get a second chance.

Drew Findling, president of the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, has seen this firsthand in 30 years of representing criminal defendants. “Someone can leave prison, but in many ways, they remain imprisoned. They can’t get the job that pays a living wage. They can’t get into an apartment. They can’t get the loan for a home, they can’t even feel what it’s like to be a normal citizen,” Findling says. “You realize there are all these punitive measures the government takes that, while it doesn’t keep you caged, it does, in many ways emotionally and professionally and socially, keep you caged.”

According to the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction, there are nearly 45,000 measures that can stand in the way of a person with a criminal record seeking to lead a normal, productive life. These restrictions cover employment, licensing, housing, education, public benefits, credit, loans, immigration status, parental rights, interstate travel and more.

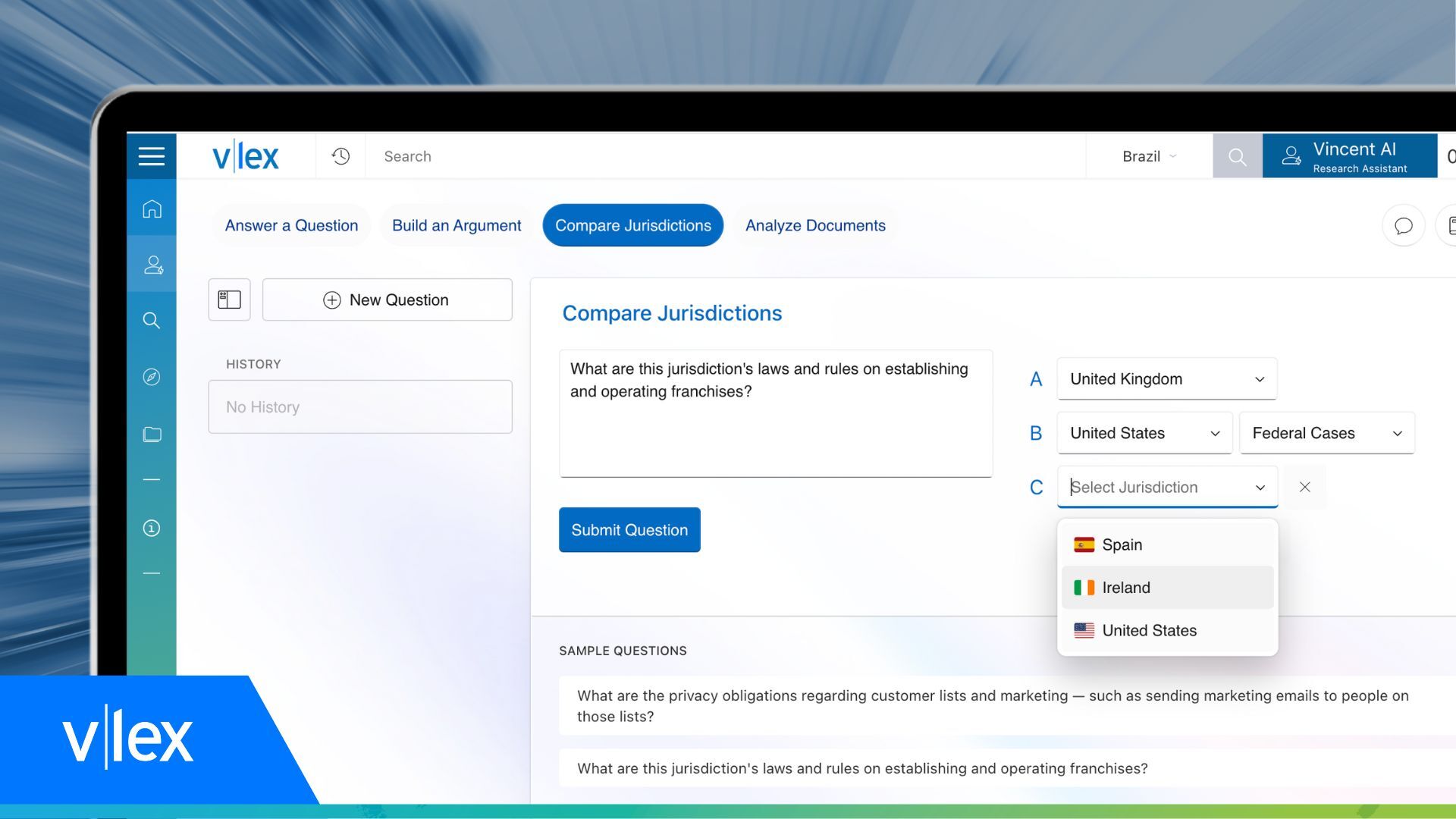

A family portrait (from left to right) of Steve Price with his siblings and mother; Price at age 19; Price in adult prison; a picture of Price’s mother, Eula.

The NICCC began as a project of the ABA Criminal Justice Section and was launched in 2014. The idea was to create a database of laws and regulations that affect those with criminal records and make it available to lawyers, lawmakers and advocacy groups.

Margaret Love, a Washington, D.C.-based attorney who was the first director of the NICCC, and is now executive director of the Collateral Consequences Resource Center, recalled that what she found was distressing. “The phenomenon of collateral consequences is, in a sense, a part of the sentence,” she says. “People get tarred with a criminal record, whether they go to prison or not, and that can be disabling for their entire life. Until recently, there have been fewer and fewer ways for people to get out from under the cloud of a criminal record. The fact is that even arrests come up on rap sheets, and they are frequently used to disqualify people.”

While the number of such consequences remains high, efforts to reduce them have been successful. According to the resource center, 32 states, the District of Columbia and the U.S. Virgin Islands enacted at least 61 laws in 2018 aimed at reducing barriers to successful reintegration for those with criminal records, continuing a trend the center has tracked for the past six years. By the end of 2018, every state passed laws to address the problem.

See also: ABA offers opportunities and resources to address collateral consequences

In addition, more than 30 states and 150 cities in recent years have passed “ban the box” laws that prohibit employers from asking about arrests or convictions on job applications, according to the nonprofit National Employment Law Project. While this may stop employers from immediately tossing out applications from those who check the box, they’re still free to conduct criminal background checks before making hiring decisions. Many small businesses are also exempt from the law based on the number of people they employ.

Being a person of color adds another barrier to getting a job—criminal record or not. According to the NACDL report “Collateral Damage: America’s Failure to Forgive or Forget in the War on Crime,” white people with criminal records are more likely to get callbacks for job applications than black people without criminal records.

Despite efforts to remove barriers for those with criminal records, the most harmful consequence remains the hardest to shake. “It’s the stigma—which encourages discrimination,” Love says. “And most of the time, it’s not embodied in any particular law. It’s just, ‘We don’t want to hire somebody with a criminal record.’ ”

Recognizing a need to bring greater attention to this issue, Findling helped organize “Shattering the Shackles of Collateral Consequences,” an NACDL conference that drew attorneys, policymakers and formerly incarcerated people together in Atlanta last August. “We have a terrible system of direct consequences,” Findling says. “But also, the lingering indirect consequences that make a mockery of the notions of rehabilitation and redemption.”

No First Chance

Price grew up in Auburn Gresham, once a thriving

working-class Chicago neighborhood that has been on the decline for decades. His parents were from Mississippi, where his mother picked cotton with her brothers and sisters. His mother was married at age 14 and moved to Chicago with his father, who ran a gas station on 79th Street. He was an alcoholic who died when Price was about 6 months old. Price was not close with his three brothers and sister and felt alone much of his childhood.

When Price showed academic promise in grammar school, he says his peers mocked him. A teacher in fourth grade had complimented Price on his multiplication skills in front of the class. “I went to recess, and the whole class jumped on me. So I felt being smart was not the way to go,” he says. “There was a point where I just wanted to be accepted, and I got involved in the gangs and the street life. Once I got involved in that, it was an ongoing thing, and I stayed in trouble for a very long time.”

Steve Perkins: “We always told him he had a place to come, but he had to earn his place.” Photo by Wayne Slezak

Price would intentionally get in trouble to get attention from his mom, who cleaned houses, sometimes seven days a week. He looked forward to when she would have to pick him up from the juvenile detention center. “That was the time we could spend together, on the ride home,” he says, “because once we got home, our time together was over with.”

When Price turned 17, he made his first trip to adult prison. “My first charge as an adult was for burglary, and they gave me four years,” he says. “As I went into the prison, I learned quickly that I had to be this cold, callous person, because otherwise, you were going to be looked at as weak.”

He fought his way to getting the respect he needed to survive on the inside, but he lacked something more important that could help him on the outside: an education. “They had programs, but I was too ashamed to admit that I didn’t know how to read. I couldn’t tell anybody about it,” he says.

When Price was released, his job prospects were close to zero. “So, with me coming out of prison at the age of 19 and unable to read, I couldn’t get a job because I couldn’t fill out an application. So, I went right back to the street life and continued my life of crime.”

He got busted again. This time, seven years for burglary and auto theft.

REBUILDING LIVES

Apostle Joseph L. Stanford is founder and pastor of Ambassadors for Christ Ministries in the Auburn Gresham neighborhood where Price grew up. In the years since Price was a young boy, the area has suffered from economic hardship, white flight, disinvestment, unemployment and high-crime rates. Under Stanford’s leadership, the church has created several not-for-profit, faith-based organizations to help rebuild the neighborhood, prevent violence and offer services to those released from prison like Steve Price. Stanford has counseled many people seeking a second chance.

“Some people don’t have a first chance,” Stanford says. “They’re born into poverty. They’re born into drugs. Peo-ple go into prison illiterate and come out illiterate and can’t get meaningful work.”

It’s part of a cycle that Stanford and his colleagues are trying to break. “We can’t look to the government to help us. We need to help ourselves. If we don’t help ourselves, no one is going to help,” he says. To that end, the church founded the Target Area DevCorp, a grassroots community organization that has a program to assist people released from prison. Its services include job readiness training, counseling and anger-management programs.

Many workers at Target Area are formerly incarcerated, and they visit prisoners before their release to talk about the re-entry program. “It’s important that we go inside before they get out,” says Autry Phillips, Target Area’s executive director. “We build relationships with people on the inside. It’s really important that people on the inside know that someone on the outside cares about them.”

Joshua Coakley: “They are lacking job readiness. They say they want a job, they say they want to be employed, but they don’t know the first thing about getting up, getting ready on time, how to talk during an interview.” Photo by Wayne Slezak.

Joshua Coakley, 43, has regularly visited the Sheridan Correctional Center, a prison that offers substance abuse programs. His background gives him credibility to create trust among the men. But addressing their addictions is not enough for most of them once they get out. “They are lacking job readiness,” Coakley says. “They say they want a job, they say they want to be employed, but they don’t know the first thing about getting up, getting ready on time, how to talk during an interview. About 90 percent of our guys never worked. They have no work experience whatsoever.”

That’s where Target Area comes in. As part of the re-entry program, they provide anger management counseling, basic job readiness training and referrals to temp agencies. “They need money, a place to stay and food,” says Coakley, a licensed minister and a re-entry director at Target Area. “With some of the guys coming home, their mindset is that they’re not concerned about education right now. It’s, ‘I’m concerned about the sandwich I want to eat.’ ”

Price might have benefited from such a program but was unaware it existed just blocks from where he lived. Instead, he spent his 20s in and out of prison for retail theft, drug possession, forgery and burglary. He used the time wisely by learning to read, studying for his GED certificate and enrolling in barber’s school—but even that was no guarantee he could make it on the outside.

Changing the PaTTERN

Across the country, organizations large and small, public and private, are working to help men and women successfully transition from prison to life on the outside. Many have been funded through federal grants under the Second Chance Act of 2007, long supported by the ABA and reauthorized by Congress last year. The act passed with bipartisan support during the administration of George W. Bush, who pledged during his inauguration to help prisoners reintegrate into their communities.

To learn what kinds of approaches work to reduce recidivism, the Koch Foundation, one of the country’s most politically conservative organizations, is funding an effort to develop evidence-based programs to help people like Price break the cycle.

Mark Holden, senior vice president and general counsel of Koch Industries Inc., is chair of an initiative known as Safe Streets & Second Chances. It aims to reduce recidivism by giving prisoners the tools they need to return home to get jobs and start their lives again.

“The fact that so many people return to prison again and again is completely unacceptable, it’s disgraceful and it’s not good for anybody, particularly for communities, for the individuals in prison and their families,” Holden says. “We want to find the best practices we have and see if it can’t be a game changer as far as keeping people out of prison once they’ve been in.”

To start, Holden says those going to prison should also be planning for their release. “Our goal for re-entry is that it needs to begin from day one of incarceration,” he says. “Every individual who is going to be returning to society at some point will have their own personalized plan for re-entry.”

To test that strategy, Safe Streets is conducting a study at prisons in Florida, Kentucky, Pennsylvania and Texas where participants will develop such personalized re-entry plans. “These are people who often aren’t asked what they want or what their aspirations are,” Holden says. “We’re asking them those questions. Almost everyone wants to work more, they want to learn more, they want to have positive relationships, they want to be a positive part of their community.”

Carrie Pettus-Davis, an associate professor at Florida State University, is leading the study, which she says will compare those who have personalized plans designed by her team to those who receive the states’ own re-entry services.

Pettus-Davis found that the majority of those returning from prison rely on a case management model, which means mostly getting referrals to various re-entry services throughout their communities. “The problem with that is oftentimes people are referred to waitlists, or they’re referred to low-quality services or they are referred to places they can’t reach because of geographic or transportation barriers,” she says.

She believes that those who receive consistent services and plan their exit from prison while still incarcerated will fare better. “Ultimately, we believe a focus on well-being that happens using a continuum of care starting from the beginning of incarceration and ending afterwards is going to produce better outcomes,” she says.

This focus on an incarcerated person’s overall well-being represents a shift in how re-entry programs are modeled, Pettus-Davis says. It’s based on helping them develop healthy thinking patterns, effective coping strategies, meaningful work trajectories, positive social engagement and favorable interpersonal relationships.

THROUGH THE FIRE

By the time Price was in his 40s, he was still circling through the revolving door of prison with more convictions for drug possession and theft. He couldn’t shake his addiction, didn’t get referrals for treatment once he was out and didn’t seek help on his own. During his years in and out of prison, Price fathered three children he rarely saw.

After being released in the winter of 2009, Price promised himself he’d work harder to find employment. He was thrilled when he landed a job as a maintenance engineer at a senior citizens’ home. “I was on the job for seven days,” he recalls. “One day I was out doing snow removal, and the lady called me into the office and said, ‘You need to turn in your keys and go. Your background check came back, and we can’t keep you.’ ”

He was crushed. “That really messed me up. I loved that job, and they told me I was doing a good job,” he says. “That devastated me. I started getting high. I couldn’t deal with the rejection.”

Price caught another conviction for burglary and was sentenced to six years. But then, he did something he never did before. “I was ready to start learning about my addiction,” he says. He applied to join a substance abuse program and was accepted to the Sheridan Correctional Center.

One day, the prisoners got a visitor. His name was Steve Perkins, public safety manager at Target Area DevCorp, who came to talk about its prisoner re-entry program. Afterward, Price walked up to Perkins and told him he grew up in that community. “That’s how he introduced himself,” Perkins recalls. “After that, when I would come back, I’d always have conversations with Steve.”

When he got out in 2013, Price signed up for the re-entry program. His mom once again allowed him to move back home.

“My mom was a great lady. No matter what I did, she supported me,” Price says. “But she didn’t understand my life. She was a good Christian woman her whole life. She didn’t understand what I was going through or how to help me in any way.”

Price seemed to be doing well, but then he stopped going to the program. He says he wasn’t used to being around so many people on the outside. “All this distrust and paranoia kicked in, and I started using again,” Price says. “It didn’t take long. Six months later, I was locked back up.”

He got eight years for burglary. It seemed to be his destiny.

EARNING HIS PLACE

Four years later, at age 56, Price was once again released from prison and moved back home with mom, who was in her upper 80s by then. He had grandchildren, and he was just plain tired of being incarcerated. He got ill in prison and developed blood clots in his legs, which required a liver transplant.

After coming home, Price decided to go back to Target Area DevCorp, despite having let himself and the staff down.

“We always told him he had a place to come,” Perkins says. “But he had to earn his place.”

Price stopped by every day asking how he could help. “I’m available. If you need me, I’m here,” he would say. He cut hair for men at group meetings and did odd jobs around the building. Perkins says it took time, but Price earned back trust. “I had to have him work for free for a while. I wanted to see if he was serious,” Perkins says.

“They made me feel wanted,” Price says. “They made me feel like they’re not going to judge me. They made me feel like I was part of a family—and I never felt that before. Volunteering and giving something back made me feel good. It made me want to get involved in even more.”

After volunteering for months, Target Area offered Price a paying job with benefits as a violence interrupter. “We go into communities and talk to people, and if something is going on, we try to defuse the situation,” he says.

Steve Price found people willing to believe in him at Target AreaDev Corp on Chicago’s South Side. Photo by Wayne Slezak

On the streets, he runs into people he knew from kindergarten as well as a new generation of young people at risk of falling into the same patterns that put Price in prison. “Knowing my history, they were shocked to see me doing this,” he says. “When I get out there and talk to these people, I see me. I see everything I was involved in, and it makes me want to help them turn their life around. I tell them if I can change, anybody can change.”

Price says he’s motivated largely by wanting to be around for his children and grandchildren. “What I had to realize was that it was no longer about me,” he says. “I realized that when I went to prison, they were right along with me. I didn’t realize how much they were hurting.”

He hopes someday to find other work, although he favors working with young people and counseling troubled youth. “People who need inspiration and guidance,” he says.

His mom died last fall at 89. “My mom passed away after all this time, seeing me go in and out of jail and getting in trouble,” Price says. “The best part is that I was able to turn my life around before she passed, and she got to know I’m OK. I was glad to know she didn’t have to worry about me anymore.”

Price knows he’s made poor choices but wishes he had a helping hand when he most needed it—a father, a mentor, an employer willing to give him a shot. “We need a second chance,” he says. “We need someone to say, regardless of what you’ve done in the past, let me allow you to try something different. We need that.”

Correction

Print and initial web versions of “Marked for Life,” May, should have credited the National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction as the source for the number of collateral consequences. The NICCC began as a project of the ABA Criminal Justice Section. The Collateral Consequences Resource Center is an independent, nonprofit organization.The Journal regrets the error.