Executive Branch

The executive branch pushes the boundaries of the separation of powers

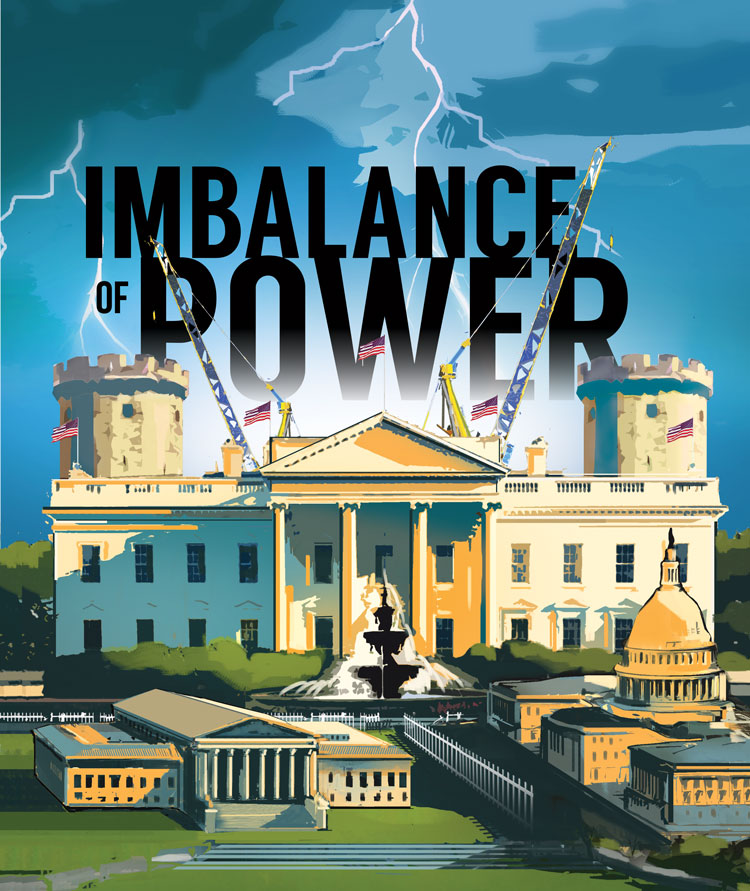

Illustration by David Owens

Most view the discussion through their own lenses, and many legal scholars are no different.

Take, for example, the president’s direct attacks on the judiciary in general and some individual judges in particular—calling one a “so-called judge”—when his travel ban ran into a wall in the courts.

For Josh Blackman, a libertarian professor at South Texas College of Law Houston, “The tweets are all bark and no bite, and don’t go anywhere. It’s just the president venting, and I wish he wouldn’t do it. But there actually are policy achievements going on.” Blackman notes that despite presidential fulminations, the Justice Department has continued to follow law and procedure.

Blackman’s former teacher Ilya Somin at the Antonin Scalia Law School disagrees. He’s a public choice theorist who believes that the widespread “rational ignorance” of voters—people too busy at work and life to study politics—is harming our system of government.

“I think there is bite, and the barking itself has some significance. If he’s perceived as getting away with this and not paying a political price, then future politicians will say, ‘If he can get away with it, maybe I can, too.’ It becomes the new normal.”

But then Tara Leigh Grove, a professor at the William & Mary Law School who studies how the federal judiciary is affected when brought into hot-button issues, believes the system has shown remarkable resolve. She shares Somin’s fear of possible long-term implications as well as Blackman’s emphasis on the Justice Department having hewn to the law.

See sidebar: Tipping the balance of justice

“As soon as a single federal district judge issued an injunction with the first travel ban,” Grove says, “the Department of Homeland Security complied.”

Later, another federal judge issued an injunction against President Trump’s move to rescind President Barack Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals immigration policy, and 700,000 people got to remain in the U.S. for an indeterminate period.

“This was because a single judge ruled against the government,” Grove says. “A lot of people don’t realize how extraordinary that is when compared to other societies. In our culture, it’s just the norm.”

Josh Blackman: “The tweets are all bark and no bite, and don’t go anywhere. It’s just the president venting, and I wish

he wouldn’t do it.” Photograph courtesy of South Texas College of Law Houston.

One’s position on such a conversation between governmental branches doesn’t necessarily depend just on what one believes, but perhaps also on presidential cycles. When a new administration brings a change in political party, there is a reversal of polarity in mindsets.

Blackman likes how Harvard Law School professor Adrian Vermeule put it in his blog just weeks after Trump’s election, describing a scene in any movie adaptation of a Jane Austen novel, when two lines of dancers switch to opposite sides of the ballroom. The dance continues with the same structure, but the dancers are suddenly facing in opposite directions.

Vermeule writes that “after a short period of confusion and recalibration, we would see liberal lawyers become critical or suspicious of presidential administration under Trump, but the conservative lawyers will make their peace with the administration. We will see a bewildering switch of places, but no major change in legal doctrine.

Tara Leigh Grove: “As soon as a single federal district judge issued an injunction with the first travel ban, the Department of Homeland Security complied.” Photograph courtesy of William & Mary Law School.

SHIFTS IN THE BALANCE?

There has been, though, a significant change in the public face of the presidency, and the kind of tone set at the top. But is President Trump actually upsetting the balance of power? Is his characteristic breach of norms—“tough talk” and sometimes mercurial action—itself unsettling enough to throw things off? Or is this just his time on the stage and no more?This is all playing out as the three branches of government work through their duties: Congress making laws; the executive implementing them; and the courts resolving inevitable questions and disputes. But it is not so simple as a game of rock-paper-scissors

There also is a fluid dynamic of communication between the three branches, a complex dialogue that is sometimes subtle, sometimes sharp. It is clear the tenor and method have changed. Trump—to the expectation of much of his political base—doesn’t waste time on subtlety and puts a serrated edge on sharpness.

As part of the growing discussion, the ABA’s theme for this year’s Law Day, chosen by President Hilarie Bass, is “Separation of Powers: Framework for Freedom.” Congress in 1958 set May 1 of each year for celebration of the rule of law, as proposed the previous year by then-ABA President Charles S. Rhyne.

“The threats to the separation of powers and the public’s and many in government’s apparent lack of understanding of the concepts of three separate but equal branches of government led me to make this my Law Day 2018 theme,” Bass says. “Without a healthy and functioning separation of powers, we run the very real risk of degenerating into tyranny.”

While other presidents in recent years had several or more major legislative victories early in their terms, Trump’s most significant policy accomplishments have come through assertions of executive power—a bag of tools that includes executive orders and the appointment of agency heads.

A number of Trump’s agency appointments, including Cabinet members, have been controversial in ways that, among other things, indicate radical policy changes—the individuals’ beliefs and goals are antithetical to the agency’s mission or customary activity.

For example, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, when he was Oklahoma’s attorney general, had sued the agency, challenging its clean power plan—and the EPA itself is now moving against it. And the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s acting director, Mick Mulvaney—a sharp critic of the agency since before it was launched and also director of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget—requested zero funding for the CFPB for the first quarter of this year. Along with that largely symbolic gesture, given that the agency had reserve funds, the CFPB dropped several high-profile lawsuits against payday lenders.

These moves are part and parcel of the Trump administration’s declared war on the so-called administrative state. That enemy is composed of scores of agencies with “armies of bureaucrats” working under the “misguided notion that independent experts rather than our elected representatives are best suited to govern national affairs,” White House Counsel Donald McGahn said in a November speech.

Addressing the Federalist Society’s annual convention—he’s been a member since law school—McGahn said, “The greatest threat to the rule of law in our modern society is the ever-expanding regulatory state.”

Correction

“Imbalance of Power,” April, should have identified Ilya Somin as being at the Antonin Scalia Law School.The Journal regrets the error.