It was another big term for amicus curiae briefs at the high court

Citations soar with Sotomayor.

It was a big term for little green booklets at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Merits briefs at the high court are filed in booklet form, with an array of specified colors. Amicus curiae, or friend of the court, briefs have covers of either light green for those backing the petitioners or neither party, or dark green for the respondent’s side.

With a 2012-13 term full of contentious cases on gay marriage, voting rights, race in college admissions and DNA, amicus briefs in light or dark green were filed at a seemingly unprecedented rate.

“It’s the rare case anymore that doesn’t have any amicus briefs,” says Paul M. Collins Jr., a political science professor at the University of North Texas in Denton. “The numbers increase as interest groups view it as a strategy.”

The role of amicus briefs in the Supreme Court is the subject of considerable study by political scientists and legal observers. “The court continues to cite amicus briefs with increasing frequency,” says Collins, the author of Friends of the Supreme Court: Interest Groups and Judicial Decision Making, a 2008 treatise.

The numbers for the 2012-13 term back his conclusions. Seventy of the 73 cases, or nearly 96 percent, that received full plenary review attracted at least one amicus brief at the merits stage. The proportion has been on a steady upswing for decades.

A BRIEF RUNDOWN

Leading the pack was Hollingsworth v. Perry, the case involving California’s state constitutional prohibition of same-sex marriage. It had 96 amicus briefs at the merits stage. The court ruled 5-4 that proponents of Proposition 8 lacked standing to press their case on appeal.

The related case of United States v. Windsor, in which a different 5-4 lineup struck down part of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, drew 80 amicus briefs. (Some briefs covered both cases.)

The term’s big affirmative action case, Fisher v. University of Texas at Austin, drew 92 amicus briefs total weighing in on whether the school’s race-conscious admissions program was constitutional. The court held 7-1 (with Justice Elena Kagan not participating) that achieving racial diversity remained a compelling governmental interest but that a federal appeals court had not properly applied strict scrutiny to the admissions plan at issue. The justices remanded the case for further review, an outcome that let both sides claim victory.

Next was Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum Co., involving extraterritorial application of the Alien Tort Statute, which drew 51 amicus briefs just for the broader legal question on which the court requested reargument this term.

Two cases tied with 49 amicus briefs filed for each. One was Shelby County, Ala. v. Holder, in which the court struck down the coverage formula for which jurisdictions had to get federal approval for electoral changes under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The other was Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics Inc., in which the court held that naturally occurring DNA segments were not patent-eligible.

Last term, the historic cases involving President Barack Obama’s signature health care law drew 136 amicus filings. “Just when you thought it couldn’t get any bigger with last term’s blockbuster health care case, this term you see an increase in almost every category” of amicus briefs, says Anthony J. Franze, counsel in the Washington, D.C., office of Arnold & Porter who studies amicus trends.

Ilya Shapiro, a senior fellow in constitutional studies at the Cato Institute, a Washington think tank devoted to free markets and individual liberty, noted that filing an amicus brief in the Supreme Court is a relatively inexpensive yet effective way for an organization to make a legal or public policy point.

Private groups such as Cato can file a brief for little more than the cost of printing—about $400 if the group provides printers a PDF, Shapiro says. (Costs could quickly escalate for groups or companies that hire a top-notch law firm to write the brief.) Cato is a frequent filer of amicus briefs, and while none of its briefs was cited by the court this term, the group did go 15-3 in the positions it took. Shapiro says Cato was the only amicus to generally go 3-for-3 in the term’s biggest issues: It supported stronger scrutiny of race-conscious admissions, same-sex marriage, and the decision to rein in the Voting Rights Act.

Scholars have looked at amicus briefs on various levels. In a 2004 survey of former law clerks who had served over several decades, the clerks told researcher Kelly J. Lynch that, as he put it in an article in the Journal of Law & Politics, “most amicus briefs filed with the court are not helpful and tend to be duplicative, poorly written or merely lobbying documents not grounded in sound argument.”

Still, the clerks in the survey addressed how a good amicus brief could stand out from the pack. They advised against repeating arguments found in the parties’ briefs; urged that briefs be kept, well, brief; and suggested involving top-notch Supreme Court advocates or academics.

More recently, Harvard law professor Richard H. Fallon Jr. examined—and was somewhat critical of—the growth of amicus briefs by groups of professors or scholars, of which there was no shortage this past term. Fallon said such briefs raised ethical questions about whether the signers were leveraging their credibility as scholars.

AN INSTRUCTIVE PROXY

Just how influential are all these amicus briefs on the justices and their opinions? It isn’t possible for outsiders to know for sure, of course, but scholars have settled on a substitute that they believe is instructive: the frequency of citations to an amicus brief in any majority, concurring or dissenting opinion.

“In general, we use citation rates as a helpful proxy for influence,” says R. Reeves Anderson, an Arnold & Porter associate who has written about amicus briefs with Franze.

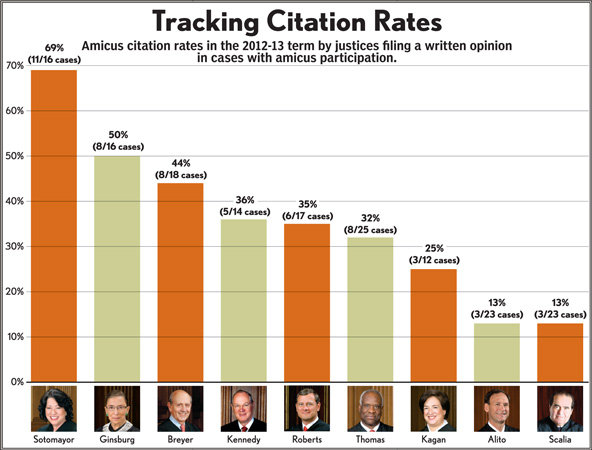

Justice Sonia Sotomayor cited amicus briefs in 11 of her opinions this term, or 69 percent. At the bottom were Justices Antonin Scalia, who has traditionally been a bit dubious of amicus briefs, and Samuel A. Alito Jr.—both with three opinions containing such citations.

In the 2011-12 term, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy had the most opinions with amicus citations, while in the term before that, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. led the pack.

Some of the citations this term were much more than a passing reference. In Perry, Roberts cited an amicus brief filed by Walter Dellinger, a former acting U.S. solicitor general under President Bill Clinton and now a partner in the D.C. office of O’Melveny & Myers.

Dellinger, an influential Supreme Court advocate, laid out an argument for why proponents of Prop 8 lacked standing to appeal a federal district court decision striking down the California ban on same-sex unions.

“As one amicus explains, ‘the proponents apparently have an unelected appointment for an unspecified period of time as defenders of the initiative, however and to whatever extent they choose to defend it,’ ” the chief justice cited approvingly from Dellinger’s brief.

“It was certainly rewarding to know the brief was being read on the court,” Dellinger says. Noting that the brief was filed in his name only, he adds, “This brief was entirely about the substance of the standing argument and not about one or more organizations weighing in on the merits.”

Speaking more generally about the growth of amicus briefs, Dellinger says many are from groups that are really just saying, “Me too!”

A different style of amicus reference came from Justice Clarence Thomas in his concurrence in Fisher, in which he made it clear he would rule that a state’s use of race in college admissions was categorically prohibited by the equal protection clause.

“Tellingly, neither the university nor any of the 73 amici briefs in support of racial discrimination has presented a shred of evidence that black and Hispanic students are able to close a substantial gap [in preparedness] during their time at the university,” Thomas wrote.

Collins of the University of North Texas says he is finishing a paper that seeks to provide a more sophisticated look at how the justices use amicus briefs. The study uses plagiarism-detection software to compare passages in briefs and opinions. It’s not that he’s accusing anyone of stealing, as the justices generally cite briefs when they borrow language from them. But the software allows for a more refined look at what gets used.

“Amicus briefs are certainly capable of shaping the justices’ reasoning,” Collins says. “You see the incorporation of language from these briefs.

“But they are not the determining factor,” he adds. “It’s the rare case where the outcome actually swings on an amicus brief.”

Source: Anthony Franze and R. Reeves Anderson of Arnold & Porter’s appellate and Supreme Court practice group in Washington, D.C. Graphics by Adam Weiskind.