Love Hurts: Mich. Law Prof Explores Love and Heartache in Japanese Culture

By any measure, the murder of the Japanese woman named Yuriko and her two children was a grisly one. Yuriko endured an abusive marriage that included a forced abortion and a philandering husband who repeatedly left her and threatened her with divorce. The two fought continuously over Yuriko’s demand that her husband, Mitsutaka, change jobs and end his affairs.

Distraught and broken down, Yuriko eventually attempted suicide in front of her husband. Her attempt failed, triggering another fight between the couple and ending in Yuriko’s death.

Details of the marriage and murders are painstakingly documented in a Japanese court decision, which also notes how, immediately after Yuriko’s murder, Mitsutaka turned his thoughts to his children and strangled each one with the same rope he had used on their mother. Mitsutaka then went to his job as a doctor at a local hospital and spent time in Tokyo’s red-light district before returning home to dispose of the bodies in the ocean.

Despite the heinous nature of the crime, the Japanese judge did not impose the death penalty. Instead, the judge wrote that Yuriko was partly responsible for the murders because of her repeated confrontations with Mitsutaka and her refusal to grant him a divorce.

Love hurts, and nowhere perhaps is that sentiment more prevalent than in Japan.

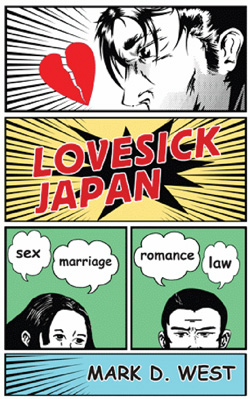

University of Michigan law professor Mark West uses the case of the murderous doctor and others to explore the curious intersection of the law and Japanese views of love, sex, marriage and romance in his new book, Lovesick Japan.

West researched more than 2,700 Japanese cases to explore a particular vision of romantic and sexual habits in the country. That vision is hard to define, West says, but “at the end of the day, the judges’ opinions suggest major problems in love, sex and marriage in Japan.”

Because Japanese law requires judges to write opinions for every case, their work offers an intriguing blend of facts and editorializing—especially when it comes to crimes relating to love. “If you ask people what love is, they don’t necessarily jump to murder.”

At the crux of West’s book is the Japanese perspective on love. Most Japanese men equate love with suffering and pain, he says, and Japanese judges often invoke this more in criminal case decisions arising out of affairs of the heart. “Love and heartache go hand in hand” in Japan, says West. “The courts there are not inventing anything new; they are just picking up on the vibe.”

“Love exists,” West says. “It is worshiped, but it is mostly pain.”

Another busy night in Kabukicho, Tokyo’s largest red-light district. Photo by Tom Wagner/Corbis Saba