May 8, 1973: American Indian Movement surrenders at Wounded Knee after 71-day standoff

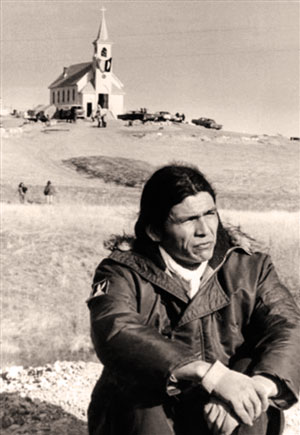

Dennis Banks. Photographs BY AP Photo/Jim Mone; AP Photo/Pool.

Established in 1889, the 60 million-acre reservation proved prey to a broad variety of white opportunism: by squatters, gold miners, merchants and a federal government that routinely ignored its own treaties. Pine Ridge was also the site of the tiny town of Wounded Knee, where in 1890, panic-stricken U.S. soldiers surrounded and massacred as many as 300 Lakota Sioux men, women and children.

Wilson, a resident of mixed race, made no secret of his loyalty to white culture and the moneyed interests favored by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. His alliance with white values was deeply resented by the more traditional tribal families; but Wilson had the support of both mixed-race voters and those who believed only outside investment could break the century-old grip of poverty.

Tensions grew critical after Wilson formed a reservation police force, Guardians of the Oglala Nation. Known colloquially as the GOONs, the force was accused of routinely harassing—even beating and arresting—Wilson’s political opposition. And when Wilson managed to avoid impeachment, angry traditionalists decided to ally themselves with members of the militant American Indian Movement.

AIM leader Russell Means and Kent Frizzell, a U.S. assistant attorney general, signed a tentative agreement on April 5, 1973, that later collapsed.

AIM leaders, typified by the charismatic Russell Means and the contemplative Dennis Banks, were schooled in 1960s radicalism, and thus inclined to splashy and confrontational acts of protest: a 19-month occupation of Alcatraz Island in 1969 and a 1972 invasion of the BIA offices in Washington, D.C.

On Feb. 27, 1973, a well-armed cadre of 200 activists marched into Wounded Knee and announced to 11 residents that the hamlet was now under the occupation of AIM. Within hours, Wounded Knee was surrounded by a formidable force of federal marshals and FBI agents, equipped with armored military vehicles and aerial support from the Nebraska National Guard.

The next 71 days were spent with both sides entrenched; the sullen South Dakota weather punctuated by frequent firefights, arson and looting, sporadic sniper attacks and occasional negotiations—all played out before a mass of media attention. Two federal agents were wounded by gunfire—one paralyzed—and two protesters were killed. After Lawrence Lamont, the second protester, was killed on April 26, there was an uptick in negotiations to end the siege. On May 8, at least 120 weary protesters surrendered to federal authorities. And just eight months later, Banks and Means were before a federal jury on 11 charges, including arson and conspiracy to assault.

But the summer of 1974 was the summer of Watergate, and the trial had revealed a pattern of government overreach: outright perjury by one key witness and false testimony by another—a witness for whom the government sought dismissal of a rape accusation. Moreover, prosecutors had attempted to obscure the extent of involvement by the U.S. military—with equipment and advice—in suppressing the occupation of Wounded Knee.

In August, during a break in jury deliberations, Judge Fred J. Nichol dismissed all charges against Banks and Means, calling the conduct of government prosecutors “offensive to our traditional notions of justice.”

This article originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “AIM surrenders at Wounded Knee.”