Native Hawaiians wage an ongoing battle to organize into a sovereign nation

Shutterstock

Aloha ‘Oe

Meanwhile, not every Native Hawaiian wants any kind of Native Hawaiian government. The lead plaintiff in the lawsuit challenging the Na‘i Aupuni election was Keli‘i Akina, president and CEO of the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, a conservative think tank. He was joined by five others, three of whom also are Native Hawaiians.

Price considers these to be largely outside forces, supported by mainland political groups—but they successfully derailed the Na‘i Aupuni voting. Akina argued that the Na‘i Aupuni was having a state election in which only people of certain races may vote, just like in Rice. This violated the 15th Amendment, plaintiffs said, and also the 14th Amendment’s due process and equal protection clauses, the Voting Rights Act and more. The Na‘i Aupuni was a state actor because it was using the OHA grant money to pursue one of the affairs office’s explicitly stated goals, according to the lawsuit.

Popper says this is unconstitutional and offensive.

“To just lightly set [constitutional provisions] aside because someone has an idea about how they could create a governmental entity for their own purposes, to lightly have a voter roll where people ... are told that they can’t [vote] because they’re the wrong race—to have that in this country in 2017 is so offensive,” he says.

Popper, who came to Judicial Watch from the Voting Section of the Department of Justice’s civil rights division, thought the case was “a slam dunk.” But it was never fully decided. The case was tied up in appeals after the district court declined to issue a preliminary injunction against the voting, saying the Na‘i Aupuni was a private organization that had a private vote.

That decision in Akina v. Hawaii triggered an appeal to the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco in June 2016, as well as an emergency injunction by the Supreme Court to stop the vote counting. But long before oral arguments, the Na‘i Aupuni canceled the election and invited all the candidates to be delegates. On Aug. 29, 2016, the 9th Circuit ruled that the issue was therefore moot.

Photo of Robert Popper courtesy of Judicial Watch

Both sides are slightly disappointed that the appeals court never reached the merits of the case. Former Gov. Waihe‘e says organizers thought they had a strong case—especially after Judge J. Michael Seabright’s ruling—but didn’t want to tie up the effort in court. Popper says a December 2016 ruling from the 9th Circuit, on voting in the Northern Mariana Islands, suggests that the appeals court would have sided with the plaintiffs.

They might have another chance. Popper says if the ratification vote is privately funded, the voter roll organizers used for the delegate election—which was created by the state of Hawaii—raises many of the same constitutional issues. If a vote is held using another roll, he says, Judicial Watch still might object to any bid to seek recognition from the Department of the Interior, on statutory and constitutional grounds.

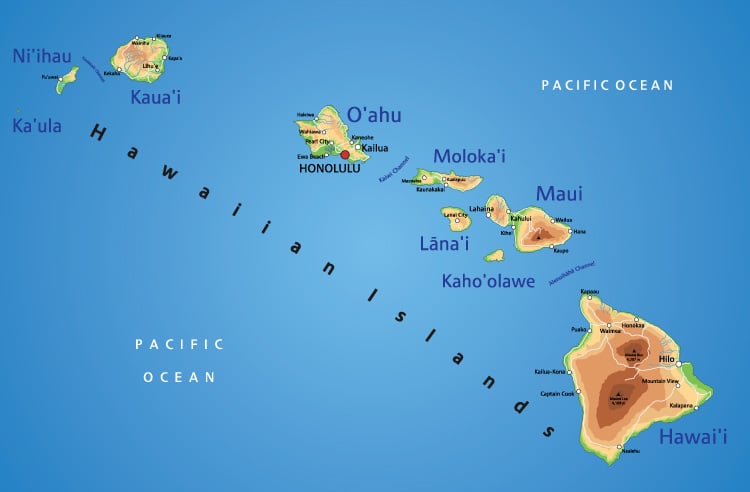

It’s not clear whether a majority of Native Hawaiians—who compose 6 to 26 percent of the state’s population, according to the 2010 census and depending on how you define “Native Hawaiian”—would seek recognition. The DOI surveyed Native Hawaiians before it made its recognition rule and concluded from written testimony that a majority was in favor. But political science professor Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua made a study of oral testimony at the Interior meetings on the islands and says the vast majority was against the rule.

It’s not because the community is apathetic, she says. During the meetings, Native Hawaiians were turning out in force to protest a proposed new telescope on Mauna Kea, a dormant volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island that’s considered to be a sacred site.

“You saw this kind of amazing activation and mobilization,” Goodyear-Ka‘ōpua says. “The DOI and Na‘i Aupuni process was a complete opposite. ... People were not engaging in that process, and there was a reason for that.”

OHA’s Price thinks those viewpoints can and should reconcile. Ultimately, the people must decide. “This is meant to be taken back to the community and then to let the community decide,” he says. “Yes or no, it’s going to be up to the Native Hawaiian people.”

Shutterstock

This article appeared in the November 2017 issue of the