Of lists and tabs: Transforming transactional drafts to make sense

Illustration of Bryan Garner by Sam Ward

What’s the single most important sentence-level reform in transactional drafting? It’s a seemingly simple idea that would require massive retraining of lawyers. Here’s the proposition: With few exceptions, every list in a contract or other transactional instrument should be set off and indented (with a hanging indent, mind you).

To make this reform possible, several things would have to happen: (1) legal drafters would need to adopt a tiered numbering system conducive to tabulating lists; (2) as part of that system, they’d have to abandon the use of romanettes, which typically clutter text and, with their varying number of characters (v as opposed to viii), disrupt the evenness of hanging indents; and (3) the syntax of existing forms would have to be modified so that lists invariably occur in the predicate—that is, the operative verb would have to precede the listings. In short, legal drafters would have to learn some new tricks.

INTO THE THICKET

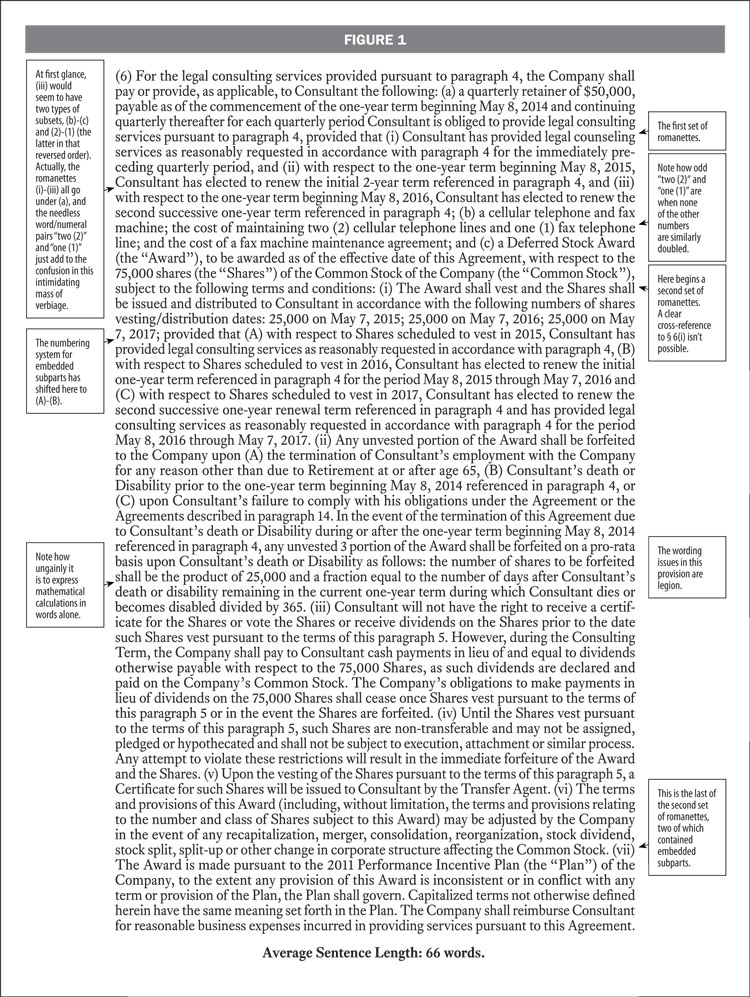

Consider Figure 1. It’s from a consulting agreement with a Fortune 100 corporation. At first glance it appears to be a single sentence, but in fact there are 13 sentences. Although there are no headings, there are generous helpings of romanettes, legalese, and mispunctuated phrases and clauses. This provision is typical of many that appear throughout the agreement.

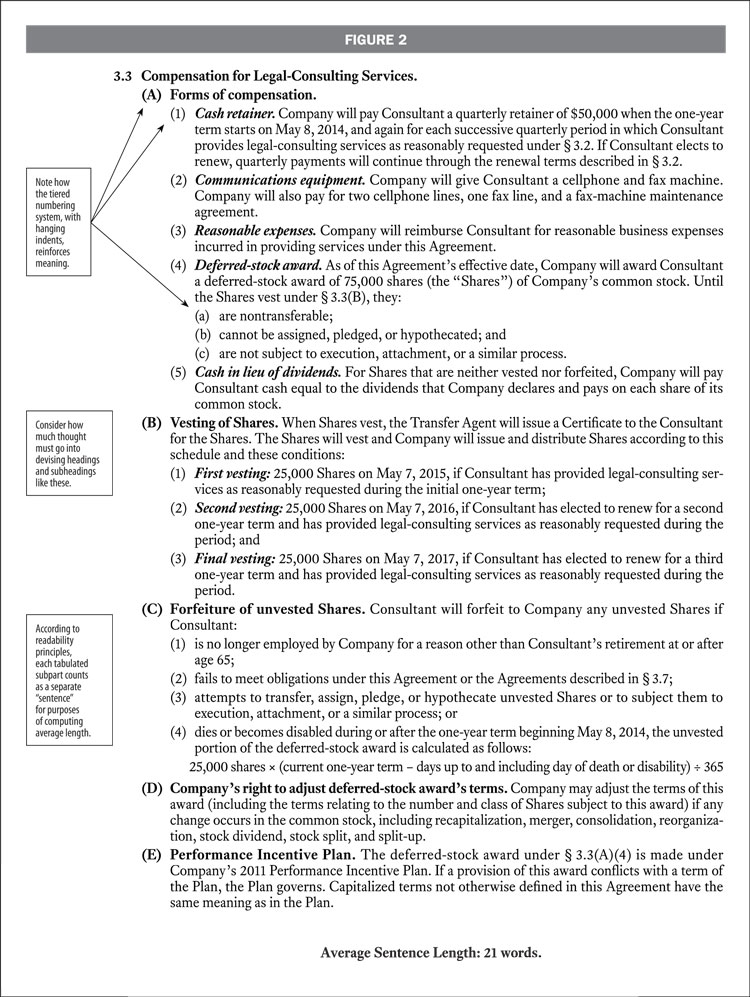

Let’s stipulate that all the content is important. Let’s accept that every detail is necessary. Now consider Figure 2. All the content is more comprehensible and, yes, attractive—with headings and subparts within hanging indents. This isn’t a mere matter of aesthetics: It’s a matter of professional accuracy and acumen. Drafting of the type you see in Figure 2 isn’t just easier for clients to follow; it’s also easier for lawyers themselves to check for precision, consistency and correctness. Simply put: If you use this style, you’re going to do better legal work.

Note one key thing that’s happened in the transformation from Figure 1 to Figure 2. What had been 13 sentences has now become 25. The average sentence length has dropped from 66 words to 21 words. Study after study has shown that this type of writing is much more readable and easier to understand. Seems obvious, doesn’t it?

Redrafting of this kind takes more than a little work. But the more often you do the work, the easier it becomes. After a while, it becomes second nature. And whenever you do it—simply listing terms with hanging indents while imposing a sensible numbering system on the document—you’ll uncover substantive deficiencies in the forms you’ve been working with. That’s a good reason to do it, even if you’re not convinced on aesthetic grounds, or on grounds that your clients will appreciate you more, or on grounds that you’ll pay closer attention yourself.

You will actually come to discover deficiencies in forms you’ve been working with for years—or even decades. Try it. If I’m wrong, write and tell me so.

And to prove I’m wrong, send me that contract with long, dense paragraphs packed with run-in lists. Please explain why there’s nothing wrong with it.

Bryan A. Garner, the president of LawProse Inc., is the editor-in-chief of

Follow on Twitter @BryanAGarner.