States help trafficking survivors overcome criminal records

Rebekah Charleston speaks at a TedX event. Photo courtesy of Rebekah Charleston.

Rebekah Charleston didn’t say a word when she was arrested in 2006 and asked about the happenings in the Nevada home she shared with her trafficker and two other women.

She didn’t tell federal authorities she was forced into prostitution at age 17 and raped countless times. She didn’t tell them she had been both robbed and strangled at gunpoint and battered by violent men in hotel rooms across the country. Her trafficker, whom she first met in Texas, made sure of it.

“He made us get on the floor on our hands and knees in front of him,” Charleston says. “He would punch us in the face and say, ‘Bitch, what’s your name?’ We would have to say ‘lawyer.’ He would punch us in the face until we fell over and got back up. ‘Bitch, what’s your address?’ We would say ‘lawyer,’ and he would punch us in the face until we fell back over.

“It was literally beaten into us that the only word we were allowed to say was ‘lawyer.’”

The year 2020 is the centennial of the 19th Amendment. A hundred years after getting the vote, what do women’s legal rights and representation look like? The ABA Journal’s yearlong series examines these issues.

Additional Resources

• 19th Amendment Centennial of Women’s Right to Vote

• ABA Commission on the 19th Amendment

Federal authorities arrested Charleston in connection with a prostitution investigation into her trafficker. Charleston refused to turn on him and was charged with conspiracy to commit tax evasion. She accepted a plea deal and spent 13 months in prison.

By the time she moved to Texas to restart her life at age 30, she had at least 10 arrests for theft, solicitation and trespassing, a large gap in employment history and almost $1 million of debt—largely due to her trafficker putting homes, cars and credit cards in her name and not paying the bills.

She went to college, earning both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in criminal justice, and now she serves as the executive director of Valiant Hearts, a North Texas nonprofit organization that seeks to end sexual exploitation.

Despite her success, Charleston found that life wasn’t without its struggles. Like many trafficking survivors with criminal records, she felt shame when forced to explain her history when applying for a job or when trying to find a place to live.

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act, the first federal anti-human trafficking law, was enacted in 2000, around the same time the international community formally recognized the issue. States soon followed with their own laws that largely focused on how to catch and prosecute traffickers.

But states failed to recognize that victims also got caught in the criminal justice system, often facing arrests and convictions for theft, drug possession, prostitution and other crimes that occurred during their trafficking.

In recent years, Hawaii, Nebraska and Nevada introduced laws to help trafficking survivors clear their records and overcome obstacles to employment, housing and education. Other states, including Connecticut, Kansas, New Jersey and New York, are moving forward with more proposed legislation.

See also: State laws provide for civil actions and other creative remedies for trafficking survivors

“Generally, for women in prostitution, it began as children for them, and they stayed in because of all of those barriers to exiting exploitation and how hard it is, especially when you get a criminal record,” Charleston says. “You have a scarlet letter on your chest.

“People look at you from the outside and think, obviously, you are choosing to be there, you can get away anytime you want. But they have no idea how we get treated in public when we do get away.”

Defining the problem

Karen Countryman-Roswurm describes human trafficking as the commodification and exploitation of a person for the purpose of sex or labor. Despite a common misconception, it doesn’t even need to involve moving that person from one place to another.

“It’s that simple,” says Countryman-Roswurm, the executive director for the Center for Combating Human Trafficking at Wichita State University. “And I believe it’s on the continuum of violence, not so completely separate and siloed from other forms of violence.”

It can be difficult to identify victims of trafficking since they can be convicted of the crime themselves if they are forced to recruit others. Determining the full scope of the problem also can be challenging when survivors are afraid to come forward or authorities fail to identify them when they are arrested for other crimes.

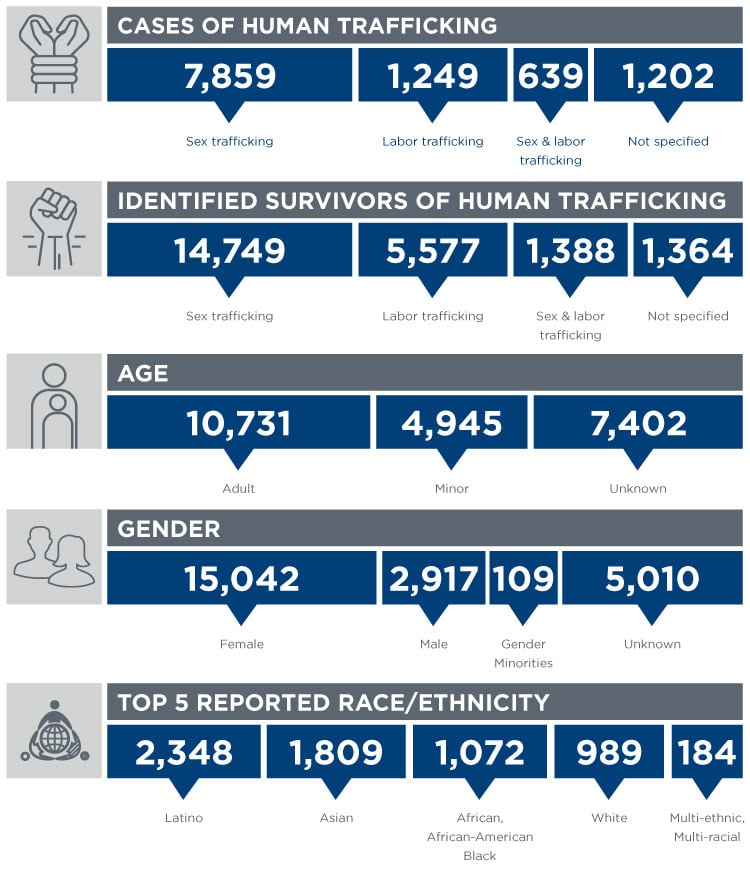

Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit organization Polaris operates the National Human Trafficking Hotline to provide survivors with support and resources. The hotline has handled more than 50,000 cases since 2007 and maintains what it calls one of the largest publicly available data sets on trafficking in the country. The hotline identified 10,949 reported cases in 2018, representing a 25% increase from the previous year. It also shows an upward swing each year since 2012, when 3,257 cases were reported.

2018 data provided by the National Human Trafficking Hotline

While nationwide data on the number of survivors with criminal records isn’t available, the National Survivor Network—a coalition of nearly 300 trafficking survivors—released its own study, which found 123 of 130 respondents had been arrested. About 40% were arrested at least nine times.

State by state

Washington was the first state to criminalize human trafficking in 2003, but it would be seven more years before New York permitted survivors to clear certain charges for prostitution and related offenses from their criminal records. Its law was passed largely in response to the advocacy of sex workers’ rights organizations.

Nearly every state has since allowed survivors to seal, expunge or vacate some criminal records related to being trafficked. However, measures offer only limited relief to survivors, according to a joint report by the ABA Commission on Domestic & Sexual Violence’s Survivor Reentry Project, Brooklyn Law School, the University of Baltimore School of Law and Polaris that analyzes and rates state criminal record relief laws.

Kate Mogulescu, an assistant professor at Brooklyn Law School and a co-author of the report, considers vacating convictions the “gold standard.” The ideal statute would offer vacatur on the merits, meaning it confirms the vacatur was due to a substantive defect in the judgment against the survivor.

The report says the ideal statute also would apply to both convictions and arrests and include all types and levels of offenses.

Several states only provide survivors relief for prostitution or prostitution-related crimes, while Georgia, Louisiana and Missouri laws only apply to survivors who were trafficked as minors. Tennessee was on that list but since passed a law that includes adults.

Idaho requires survivors to identify their trafficker in exchange for criminal record relief, and Colorado makes them pay filing fees before clearing their records. Other states like Pennsylvania and Maryland require prosecutors to consent to relief.

“Criminal record relief laws should apply to the types of offenses for which survivors are arrested,” Mogulescu says. “The laws should be accessible and shouldn’t cost money, and people shouldn’t worry about their information being made public in a very dangerous way.”

Cause for action

The joint report helped spark legislative action in several states in the past year. Hawaii expanded its criminal record relief to anyone with a prostitution conviction without forcing them to prove they were victims of sex trafficking. Nevada, initially only permitting prostitution and related offenses to be eligible for vacatur, expanded eligibility to offenses not related to prostitution.

Mogulescu has worked on New York’s proposed legislation, which would similarly expand the possibility of vacatur to any offense committed as a result of trafficking. It also makes clear that survivors do not need to prove rehabilitation to receive relief.

Nate Van Emon, a partner in the Kansas City, Missouri, office of Stinson, is an ad hoc member of the Kansas Judicial Council’s Criminal Law Advisory Committee, which is studying potential changes to the state’s law. Kansas currently allows expungement for a limited subset of criminal offenses. One proposal would expand expungement to all offenses for trafficking survivors, while another would create a vacatur remedy that applies to all offenses.

Van Emon says the vacatur bill is modeled on a progressive Nebraska law that enacted broad criminal record relief provisions for trafficking survivors in 2018. His committee is talking with Nebraska to determine if its new law has led to people who aren’t survivors rushing to vacate or set aside their convictions, a concern often voiced when discussing changes to Kansas’ law.

“From what I have heard,” he says, “people have not been abusing these provisions. It’s still something where victims’ advocates would have to educate the population they work with about … eligibility for these remedies.”

The ABA’s Survivor Reentry Project released a new report in November that identifies best practices for prosecutors handling post-conviction cases involving trafficking survivors. It also addresses the challenges prosecutors may face in these cases.

Charleston, who has not received record relief, says it doesn’t matter whether trafficking survivors are caught by force or circumstance—they are all worthy of a fresh start. “What we know about prostituted people is they come from horrific backgrounds,” she says. “What does it say about us as a society when we look at them and say that’s all you’re good for—you deserve a criminal record for doing something out of the [utmost] necessity to survive, and have no other options?”

This article ran in the February-March 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline:”Finding Relief: States help trafficking survivors overcome criminal records”