The High Bench vs. the Ivory Tower

Illustration by Matt Mahurin

Searching for the proper understanding of a refined issue of bankruptcy law, Judge Thomas L. Ambro discovered his saving grace in a 1998 law review article.

“I felt I had found my Rosetta Stone,” wrote Ambro of the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Philadelphia, referring to an article in the University of Pittsburgh Law Review. It instructed the judge on how to write a more erudite opinion.

When it comes to law review articles, “all I ask for is good analysis that instructs and sometimes persuades,” Ambro wrote in 2006 in The American Bankruptcy Law Journal. “Who it comes from and where it appears adds not a whit to its content.”

On the other hand, when asked about the influence of such articles on Supreme Court opinions, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. dismissed them as abstract and irrelevant.

“Pick up a copy of any law review that you see,” Roberts told the 4th Circuit Judicial Conference last June, “and the first article is likely to be, you know, the influence of Immanuel Kant on evidentiary approaches in 18th century Bulgaria.”

Added Roberts, “I’m sure [it] was of great interest to the academic that wrote it, but it isn’t of much use to the bar.”

Somewhere between the Rosetta Stone and a thesis on Kantian legal philosophy lies the status of the modern law review. Few law schools or legal organizations are without one—or, more likely, three or four, as they multiply to cover the increasing number of legal specialties, such as environmental law, law and economics or civil rights.

Yet many judges and practicing attorneys spurn law reviews, feeling snubbed by the high-strung theories that professors churn out, claiming the articles are mere navel-gazing and of little use to understanding everyday law. They are aimed at a small audience of academics in one tiny field of interest, judges and lawyers say, rather than a broad readership.

Scholars respond that judges and attorneys too simply shoo away important new ideas that tie law to related intellectual fields—known as the “law and …” school of thinking, which marries legal concepts to such other scholarly pursuits as economics, sociology or history. The result, they say, are discoveries that should liberate confined legal thought to real-world problems.

What’s more, publication remains professorial currency, with tenure—the golden ring of academia—waiting for those who can stock away the most articles.

The standoff between judges and practitioners on the one hand and academics on the other is hardly a new dispute; it has been going on since the early 20th century, when law reviews flourished.

But in the wake of Roberts’ remarks, the discord has resurfaced. But this time, with the speed of the Internet, critics didn’t have to wait until the next quarterly law review to air their gripes. Instead, via email, replies came fast and furious.

“Legal scholars will on occasion take up Kant (and there’s no shame in that),” wrote University of Maryland law professor Sherrilyn Ifill in an Internet response to Roberts’ remarks. “Published law review articles offer muscular critiques of contemporary legal doctrine, alternative approaches to solving legal questions, and reflect a deep concern with the practical effect of legal decision-making on how law develops in the courtroom.”

Added Ifill, “Such scholarship can assist judges in explaining complex legal doctrine, but also in working through the application of that doctrine to modern legal controversies.”

Although the dispute persists, the underlying terrain has changed from the 1990s. As judges face overburdened dockets, depressingly low pay and the politicization of appointments, many belittle law reviews as lacking the practical advice that would help make their decision-making easier in stressful times.

“I will specifically ask my law clerks to find articles,” says Ambro, a former editor of the ABA’s The Business Lawyer magazine. “They come back saying there’s good news and bad news. The good news is that there are 32 articles. The bad news is that none is on point.”

Illustration by Matt Mahurin

‘CREEPING ELITISM’

Academics, meanwhile, face intense pressure to publish, as the proliferation of electronic publications encourages even more commentary and blogging. They also face the growing dispute over whether law school classes properly teach students to practice, and whether scholars are doing that job, rather than focusing on publishing esoteric ideas to gain tenure.

Law professor Muriel Morisey of Temple University says she notices a “creeping elitism” among law school faculty, with more importance placed on scholars who have achieved a Ph.D. in addition to their law degree.

“The trend is the increasing tendency to equate good scholarship with a certain kind of academic professionalism,” says Morisey, who responded to Roberts’ remarks as part of a lengthy comment thread at ABAJournal.com in July. There, she criticized the chief justice as engaging in a “gross generalization that is also inaccurate. Some legal scholarship has enormous utility for courts and those in practice. Some [is] not intended to have readily identifiable practical utility.”

And yet, she says, the competition for academic jobs is tight. “Some scholars don’t even get interviewed for the teaching job,” Morisey says.

The Internet not only expands academics’ reach but also provides a shortcut for judges and clerks to gain access to case law. Where once they preferred a law review article to summarize the state of the law, now they are able to hop onto Westlaw or LexisNexis or any of an abundance of research byways to access reams of precedent and analysis.

Several surveys in the late 1990s supported the declining reference to law reviews. A 1998 Oklahoma Law Review study showed a 47 percent drop from 1975 to 1996 in the number of citations by the U.S. Supreme Court, lower federal and state courts.

(A separate 2000 survey showed the ABA Journal to have been cited 17 times during the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1971-73 terms, listing it as the 13th most cited journal; in 1981-83 it was cited eight times, listed as number 22; in 1991-93, it was cited once, listed as number 66; in 1996-98, there were no cites.)

Those surveys relied on a limited list of the most prestigious law reviews, predominantly student-edited and associated with a law school. However, the surveys failed to consider the explosion in what has been called the specialty journal. Where the traditional student-run law review is dominated by academic writers, specialty journals may be published by other organizations and tend to provide a more practical look because practitioners are frequently the writers.

Including specialty journals in the data set has prompted revised looks at citation numbers. Several studies published in the last year dispute the earlier claims, saying instead that judges continue to rely on law reviews and specialty journals. Using a wider array of periodicals and a longer time span, the studies agree that 32 percent—almost a third—of U.S. Supreme Court decisions have steadily cited legal scholarship.

The “apparent decline is only that: apparent. It is not actual,” states a 2010 Wake Forest Law Review study, “The Law Review Is Dead; Long Live the Law Review: A Closer Look at the Declining Judicial Citation of Legal Scholarship.” The study also points out that judges prefer to cite law reviews and journals in areas of unsettled law—of which there are fewer.

In separate investigations to be published this year, law professors Lee Petherbridge of Loyola Law School Los Angeles and David L. Schwartz of Chicago-Kent College of Law look at the use of legal scholarship in U.S. Supreme Court and federal appellate court decisions. Their probes also broaden the number of law journals and increase the time span to 60 years.

One study focuses on the average percentage of reported Supreme Court decisions using legal scholarship from 1949 to 2009. The citation of law journals reached a high-water mark in the late 1970s and early 1980s. But instead of decreasing it leveled off, with a 32 percent increase over the entire time span. A second study shows a similar trend applying to federal appellate courts.

The Supreme Court study also showed a rise in the use of legal scholarship depending on how many justices dissented, from a 30 percent increase with one dissenter to 45 per cent with four. It also showed a 63 percent increase when a decision declares a precedent unconstitutional.

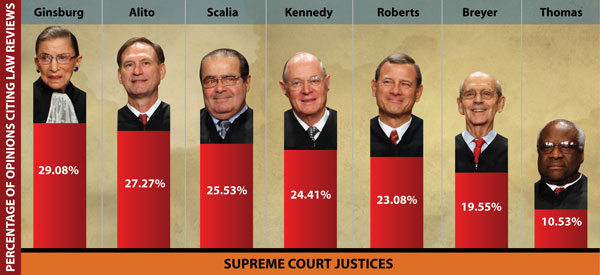

In addition, the study ranked the justices in the likelihood of using legal scholarship, from a high of 29.08 percent by Ruth Bader Ginsburg to a low of 10.53 percent by Clarence Thomas. (Because Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan are new, their decisions were not included.)

The study also ranked the last five chief justices, from highs of 27.65 percent by Earl Warren and 27.52 percent by Warren Burger to a low of 13.82 percent by William H. Rehnquist. Roberts’ use of legal scholarship is 23.08 percent—Immanuel Kant notwithstanding.

So if legal scholarship is more useful than many judges suspect, they must get something out of it. Perhaps it points the judge in a new direction, or serves as a straw man or a foil in dissent.

“The likely truth is that scholarship can be used for all different kinds of opinions,” Petherbridge says. “One could question whether there is more [of value] to practitioners in law reviews than they might think.”

In one example, Schwartz refers to the 2010 Supreme Court patent case Bilski v. Kappos, in which Justice John Paul Stevens concurred but sought to expand the definition of a “machine or transformation test.” Throughout his concurrence, Stevens cited a veritable shelfful of law review articles to help explain the development of the test in English and American legal history.

Yet, there may be a political purpose for judges and lawyers to put down law journals: the popularity of scorning scholarship as too high-minded for a practical use of law, the authors suggest.

“If there’s a narrow understanding of how you’re going to decide things, then law review articles aren’t going to be that useful,” Petherbridge says. “Judges are not making decisions largely on anything other than what’s before them.”

That thinking discloses a deeper, more philosophical problem. Judging has changed since the Warren court, which championed legal realism, the assumption that judges include broad societal concepts to widen judicial opinion-making. Warren even called law reviews “the most remarkable institution of the law school world. To a lawyer, its articles and comments may be indispensable professional tools.”

That, says Petherbridge, was a “more modern liberal view of the role of judges, that they bring a whole package of thinking” to the job. “They read the paper like anyone else, so [scholarship was] a necessary influence on their decision-making.”

Instead, courts now pursue the more conservative method of judicial minimalism and formalism, confining decisions to specific constitutional law.

Nor was Roberts the first justice to identify the disconnect—although his pungent response caught attention. In 1995, Ginsburg wrote, “If law journal citations in Supreme Court opinions are less numerous than they once were, it may be because some in the academy are writing on topics or in a language ordinary judges and lawyers do not comprehend.”

But the dispute goes back practically to the origin of the American law journal. The Supreme Court’s earliest law review citation came in Justice Edward D. White’s dissent in the 1897 case United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Association. There he cited the Harvard Law Review article “On Contracts in Restraint of Trade.”

By 1930, there were 43 law reviews, and the first tastes of published criticism. Championing the tradition was the acerbic Yale law professor Fred Rodell, who in a famous 1936 article, “Goodbye to Law Reviews,” wrote, “The average law review writer is peculiarly able to say nothing with an air of great importance.”

A legal H.L. Mencken, Rodell slammed law reviews for “long sentences, awkward constructions and fuzzy-wuzzy words that seem to apologize for daring to venture an opinion.” What was wrong with legal writing? “One is its style. The other is its content. That, I think, about covers the ground.”

Source: Professors Lee Petherbridge and David L. Schwartz from their survey of reported decisions between 1949 and 2010. Justices Sotomayor and Kagan were too new to be included. Photo by Chip Somodella/Getty Images

DISJUNCTION DISCUSSION

But in the mid-1990s the quarrel broke out in the open. Many say an article by Harry T. Edwards, then a federal appeals judge, fired the first shot.

“Too many law professors are ivory tower dilettantes, pursuing whatever subject piques their interest, whether or not the subject merits scholarship, and whether or not they have the scholarly skills to master it,” wrote Edwards in his 1992 article, “The Growing Disjunction Between Legal Education and the Legal Profession.”

“The ivory-tower elitism all too common among many ‘law and’ proponents, and their concomitant disdain for law practice, are deplorable,” wrote Edwards, now a senior judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. It ruffled enough law professors, who responded by publishing their own law review articles disputing it.

“Some of the elite schools race to find Ph.D.s, but they don’t have that much of an interest in the profession,” says Edwards in a recent interview, reflecting on the 20 years since his article. “We have to deal with real problems that have to be decided. But people in the academies, looking for tenure, it matters if they are going to get it.”

Says Temple’s Morisey: “Some think scholarship is valuable if you can say that it presents new knowledge, but my own view is that scholarship ought to be interesting.”

Despite Roberts’ chiding, many agree that there’s plenty of criticism to go around. “Go back to the 1990s and name me one article that had a significant effect on the legal world,” says Judge Ambro.

George Mason University law professor Ross E. Davies flips the remark around: “Ask any lawyer about the best written Supreme Court decision they ever read and they’ll say it’s not in this decade.”

Adds Davies, “Roberts was good-humored but critical of everyone in the system. There’s enough blame to go around, and Roberts is aware of that.”

Davies takes a special—if not personal—view of law journals. Since 1997 he has been editor of The Green Bag, a witty publication that takes a meta-perspective of the entire law journal process. Its essays include self-reflective commentary on citations, footnotes and the often Tolstoyan lengths of law review articles.

Davies dismisses measurement by citation number. “Just because you get cited doesn’t mean you said anything worthwhile.” He adds, “So if The Green Bag is a lousy law review” by not being cited, “I would rather get articles from people saying that they read it.”

Schwartz, however, defends his survey with Petherbridge. “We’re not saying that means every article is good or useful, or even that it was geared to be read by courts. The assumption is that if there’s a citation that means [the article] was used.” There may be other worthy uses for an article besides citation, Schwartz says—an unstated point of reference for a law clerk, for example.

Judges, too, sometimes will go out of their way to cite worthy scholarship. “If someone is helpful,” Ambro says, “even if someone is not a professor, then why not give them a shout?” He says he asked a clerk to locate the author of the bankruptcy article so that Ambro could thank her.

On the other hand, says Edwards, his article may have helped to tip the legal academy in the direction of more practical studies.

“The good thing about [the article] was that it caused those connected to the academy to engage in a thoughtful and productive debate,” says Edwards, who is also a visiting professor at New York University School of Law. “One of the things we started to do with law schools was to create clinical programs that we didn’t have before.”

The result, he says, should be a “mix in collegiality” among practitioners, judges and theoreticians. “I always tried to get people to be in favor of balance: clinical, theory and practice. I love to have that exchange. It’s great fun [for me] and for the students.”

Ginsburg said in her 1995 remarks, “Articles accessible and useful to judges remain in vogue.” She quoted Judge Learned Hand, who said “each is necessary to the other; each must understand, respect and regard the other, or both will fail.”

Few would agree with that more than dean Raymond C. Pierce of North Carolina Central University law school—poser of the question to Roberts at the June conference.

“So much is going on in our profession—the election of judges, the commoditization of the profession and the academy and the increase in the number of law schools—that we don’t need to take shots at anybody,” says Pierce. “This is an honorable profession that should play a major role in society in up holding justice and order. It should come together.”

When Pierce became dean in 2005 he met Judge Edwards at a conference for new law school deans. He admitted he found Roberts’ remarks “a bit surprising.”

Nevertheless, Pierce says, “once I became dean a few weeks later I did all I could to make sure this law school is part of the judiciary in its teaching and internships. There is value in having the three parts of the profession connected.”

But it’s likely the disjunction, as Edwards called it, will continue. “I’m amazed at how long the dispute has gone on,” he says. “There is still a wide margin of people who are concerned about it.”

Then again, if scholars wanted to pursue the topic of Article III limits on statutory standing, they could retrieve an article in the April 1993 Duke Law Journal. Or if they were curious to know whether the 1992 session revealed a conservative court, they might find an article in the 1994 Public Interest Law Review interesting.

The author of both: John G. Roberts Jr.