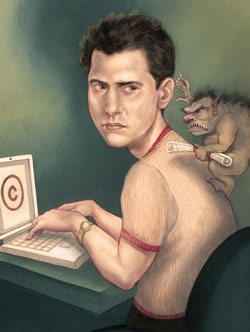

The Righthaven Experiment: A Journalist Wonders If a Copyright Troll Was Right to Sue Him

Illustration by Anita Kunz

Almost anyone who uses the Internet and is slightly curious about their own digital existence has, over the past decade, had what might be termed a Google moment. These are times, as you type your name into the search engine box, that you realize you don’t have control, that whatever you’ve done in your life is free to be appropriated and contextualized in all sorts of ways. We have identities, and then we have digital identities; and it’s not hard, when you’re looking through the digital looking glass of a Google ego surf, to wonder which is more important.

My strangest Google moment came one day last year when Google’s search engine monkeys led me to an article in the Las Vegas Sun revealing that I had just been sued. The plaintiff in the lawsuit was Righthaven, a company founded in early 2010 with the express purpose of suing copyright infringers on the Internet.

I’ve written about this company just once before, in a December 2010 article for Ars Technica that revealed that the company had picked a new target—the Drudge Report. My article included an image from Righthaven’s legal papers of a picture the company claimed to own. For this copy of a copy of a copy, I became Righthaven’s latest mark.

From there, Righthaven’s ambitions quickly unraveled. A few days later, facing a PR maelstrom for suing a journalist who had written about the company, Righthaven was forced to admit that the filing was “an internal error,” a “clerical mistake,” something that had happened because the machinery of mass suing lacked a decent check against a reporter’s fair use. The lawsuit against me was soon dismissed with prejudice.

Within a couple of months of suing me, Righthaven announced that it had suspended filing new lawsuits.

But the knocks kept coming for the company: court decisions that let defendants use substantial portions of the company’s material without penalty, judges who questioned whether Righthaven was properly assigned its claimed copyrighted material, media partners withdrawing their support, and more court decisions that ordered the company to pay legal fees to successful defendants.

By last September, Righthaven had told one Nevada federal judge it was considering filing for bankruptcy. Soon the company’s domain name was seized and, rather embarrassingly, auctioned off to satisfy debts.

Now the company’s leaders—copyright attorneys responsible for launching more than 250 lawsuits in an amazing 18-month flurry—are being investigated by the State Bar of Nevada for their actions.

And despite all of this, Righthaven CEO Steven Gibson, a partner at Dickinson Wright in Las Vegas, is not only unapologetic about everything that’s happened but also still believes the Righthaven experiment will ultimately prove successful.

“Righthaven remains the vehicle for dealing with infringements on the Internet,” Gibson told me recently. “Those who write poems, those who create movies, those who want to publish need to have a sense of protectability. If you want to have newspapers survive, protected from aggregators on the Internet, you’ve got to think about the vehicle through which that protection can occur. I don’t think anyone besides Righthaven has thought about that.”

Graphics by Kelly Hume

SEARCHING FOR SALVATION

For the past decade, a number of content studios have been experiencing their own Google moments.

They look out and, besides seeing pesky pirates and annoying aggregators, they’re bedeviled by a confluence of other factors diminishing the value of being in the content business.

Take the New York Times. A decade ago, according to one study by Business Insider, the newspaper had $540 million of operating profit. Today, even as its online operations take in more revenue than ever before, that figure has shrunk to just $61 million. Crunching the numbers, the authors of the study concluded that the newspaper’s digital business will eventually be able to support a newsroom that’s only one-third to one-half its current size.

And so big content businesses, recognizing ongoing distribution and pricing troubles, have been searching for salvation.

For many, that’s meant an attempt to broaden legal protections for content owners. Last winter, Hollywood led an effort to get lawmakers to pass new legislation intended to crack down on foreign “rogue” sites devoted to piracy. The Stop Online Piracy Act and the Protect-IP Act would have allowed the Justice Department and private copyright owners to go to court and, after getting judicial blessing, required U.S.-based websites to make efforts like blocking access to these foreign sites, cutting off support from advertisement and payment processing networks, and eliminating the presence of these foreign sites on search engines. Reaction to the controversial plan slowly escalated until the crescendo of cries reached from all corners of the Internet: Lawmakers were intent on damaging free speech protections and threatening innovation on the Web.

Meanwhile, as some content owners look outward for help, others are attempting to figure out whether there’s a more economical way to bolster the old media regime. For many, that includes adapting to the times and coming up with new or better business models. But for a few content owners, in a more agitated state of mind, it’s meant taking the existing copyright regime and doing whatever is necessary to survive.

That’s where Righthaven comes in.

Formed in 2010, the company signed agreements with Stephens Media, publisher of 75 newspapers, including the Las Vegas Review-Journal; WEHCO Media, publisher of 10 newspapers; and MediaNews Group, publisher of 56 newspapers, including the Denver Post and the San Jose Mercury News. Righthaven was assigned limited rights to the copyrights of articles and photographs from these newspapers. In return, Righthaven agreed to share 50 percent of the proceeds from any lawsuit winnings after the deduction of legal costs.

Litigation can be an expensive proposition, however, so Righthaven’s legal campaign required some game-planning about the types of targets the company would pursue. Righthaven decided it would be best to ignore both foreign pirates and any large media company that might engage in copyright infringement. Instigating a lengthy court battle or dealing with the vagaries of foreign jurisdictions would not be worth it. Instead, the company appeared to go after small proprietors such as mom-and-pop Web publishers who perhaps were a tad too aggressive in their copying-and-pasting and might bend quickly to a settlement demand.

Just a few months after it was formed, Righthaven was responsible for a tidal wave of copyright infringement lawsuits in the court system. The defendants made good stories, such as a chronically ill, autistic blogger who was slapped with a lawsuit for posting an image from the Denver Post of a TSA agent doing an airline security pat-down. (This was the same image that would later bite me.)

Along with the lawsuits came settle-or-else demand letters. Righthaven told its defendants that $6,000 would need to be handed over to quash a lawsuit. Many, including the Drudge Report, paid up so as to avoid the hassle. Some defendants pleaded poverty. And a few hired lawyers to put up a defense.

Some of those lawyers registered distaste about what was happening and felt compelled to stand up to a bully in their midst.

“Practical lawyering in an area of law I actually like often disgusts me now,” wrote one of those attorneys, Ron Coleman, on his blog.

MASS MEDIA LITIGATION

I’ve been covering media and law for nearly a decade. In that time, I’ve written about some of the key efforts to use the court system to protect intellectual property from the intrusions of the new digital vanguard.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act, signed into law by President Bill Clinton in 1998, established protections for digital content, and lawsuits in the aftermath have shaped liability for Internet service providers who host, often unwittingly, copyright infringing material. By now, it’s well-established that websites have to respond expeditiously when informed by a copyright holder of misappropriated content, but the reach of the law has had limited effect on the spread of pirated work. Infringements taken down in one spot are often put up in another, and often on foreign websites free of strong statutory obligations.

In reaction to this situation, the content business keeps flirting with the idea that the only way to really make a dent against piracy is to teach the pirates themselves a hard legal lesson by making them pay for their bad acts.

The Righthaven experiment was not the first to go after pirates on a massive scale. From 2003 to 2008, the Recording Industry Association of America took legal action against an estimated 30,000 individuals for sharing music on peer-to-peer platforms like Grokster and Kazaa. The industry group eventually backed down because of the public relations fallout and the enormous expense of the nationwide litigation.

But the idea that mass suing represents a solution to online piracy hasn’t died with the RIAA’s retreat. Far from it. I know.

In the early months of 2010, an enterprising law firm based in Washington, D.C., began a new effort to sue individuals who had engaged in copyright theft via “torrent websites”—sites that use BitTorrent technology for file sharing. What made the efforts of this firm calling itself the US Copyright Group so unique were its tactics: On behalf of its indie film clients, the firm joined thousands of “John Does” as defendants into a single lawsuit, then got a judge to subpoena ISPs for identifying information. Afterward, the alleged pirates, once revealed, would get a settle-or-else demand.

In March 2010, I wrote an article for The Hollywood Reporter describing this new legal campaign.

In the months that followed, the mass-joinder litigation started to gather national press attention. Large ISPs like Time Warner Cable resisted subpoenas. Public advocacy groups like the Electronic Frontier Foundation made it a priority to fight the “trolling” threat. And already overburdened judges struggled with the resulting storm of lawsuits.

Other companies soon adopted the tactics of the US Copyright Group, including big book publishers like John Wiley & Sons. The porn industry was able to put its own spin on the litigation with the implicit threat of revealing legal targets who refused to settle as enjoying gay porn, bestiality or other potentially embarrassing entertainments.

By February 2011, less than a year after my story came out about the US Copyright Group, more than 100,000 people in the United States were facing allegations of copyright infringement. Five years ago, during the height of the RIAA’s litigation campaign, fewer than 6,000 copyright cases were pending in the courts.

‘ARROGANCE BEYOND BELIEF’

Though the business of mass suing seems black and white for “copyright maximalists” (those who favor laws conferring broad rights and protections to content creators) and “copyfighters” (those who prefer looser protections in the name of technological innovation), the ethics of enforcement is a topic that generates some surprising opinions.

Consider Marc Randazza, who is probably the lawyer who has done the most to destroy Righthaven: His court-ordered legal fees for vigorously defending a Righthaven target forced the company to sell its own domain name. (It was purchased by a Switzerland-based company that promised to offer Web-hosting services with “a little more backbone” against legal threats.) Randazza, whose multistate practice is based in Las Vegas, calls what Righthaven did “arrogance beyond belief.”

Yet Randazza maintains he is a supporter of the general principles behind SOPA. He says that the research he started a few years ago for a paper attacking the RIAA’s mass-suing campaign led him to an opposite conclusion. “I have complete respect for what the RIAA did,” he says.

Or take Thomas M. Dunlap, the D.C.-based leader of the US Copyright Group, whose mass-joinder litigation efforts against individual pirates became a legal phenomenon. One might expect him to have sympathy for what Righthaven went through, but he’s no fan of the company either. Dunlap says the “biggest mistake they made was not doing their copyright homework.”

He’s not alone in that feeling.

Righthaven’s Gibson tells me that he believes the efforts against his company were led by those whose agenda was to weaken copyright laws. “The same folks battling SOPA were battling Righthaven,” Gibson says.

But Robert Levine, author of Free Ride: How Digital Parasites Are Destroying the Culture Business, and How the Culture Business Can Fight Back, says he believes that Righthaven messed up “a lot of stuff, including the basic idea of giving small players a mechanism to enforce their rights.”

What are perceived as Righthaven’s failings can be put into two categories: a disregard for the notion of fair use and its own lack of standing.

Fair use is the legal doctrine that holds that people should be permitted to make use of copyrighted material so long as they limit themselves to using only what is necessary to their message. Even copyright holders believe that this kind of sampling adds to the progress of culture or our understanding of society without harming the market for their work.

Indeed, Righthaven seemed to have been caught off guard when judges wouldn’t fault bloggers for reposting photographs or quoting articles. In one of the most famous Righthaven cases, a federal judge found that Vietnam veteran Wayne Hoehn, who had posted all 19 paragraphs of a Las Vegas Review-Journal editorial, was within his fair use right to do so.

The issue is one of the main reasons why Randazza decided to take on the company. “It irritated me that the company filed all those cases without any regard to fair use,” he says.

Righthaven’s inability to anticipate and prevail on these fair use challenges has alarmed some trade groups in the content industry, including the RIAA and the Association of American Publishers, which filed an amicus brief last December at the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at San Francisco in the Hoehn case. They argued that Righthaven lacked standing to pursue its copyright claims and shouldn’t be allowed to usher in “sweeping fair use pronouncements” that would imperil real copyright owners.

That leads to Righthaven’s second failing, which doesn’t get quite so under the skin of its critics but is equally significant.

The idea that Righthaven lacked standing derives from successful challenges at the district court level to the way it was assigned copyrights by its media partners in the first place. One judge ruled that only plaintiffs who have actual control over copyrights can sue. Righthaven was merely given the right to sue in its “strategic alliance agreement” with Stephens Media, and the judge said that wasn’t enough.

No topic arouses more anger from Gibson than this particular decision. He thinks it was a flawed one, emanating from a judge who was influenced by “personally vicious, unfounded, disreputable attacks” on Righthaven.

Critics like Dunlap aren’t so sure. “If Righthaven had filed [its cases] in the name of the rights-holder like Stephens Media, then I don’t think their cases would have been dismissed,” he says. “I’m not sure why they didn’t.”

Gibson could have easily represented Stephens Media as its outside counsel. Instead, he chose to step outside the lawyer’s typical role and create a shell company whose sole purpose was to sue. Why?

Righthaven observers have all sorts of theories on this. Some believe Righthaven’s raison d’être was greed, plain and simple. As lawyer-executives of such a company, they could grab a larger share of the potential settlements and judgments than they could as mere litigators. Others believe the media companies that held the copyrights wished to create a “firewall” between their operations and any potential adverse judgments and negative PR from the litigation campaign.

Gibson wouldn’t speak to this mystery directly, perhaps because it’s likely a subject of the probe by the State Bar of Nevada, which confirmed in January that it was investigating Gibson and two other Righthaven lawyers without giving any details. But during our conversation, Gibson did offer some hints.

THE RESULTS

I contacted Gibson 10 months after I had been sued by his company.

I emailed him to see if he’d talk, and I told him truthfully that I harbored no hard feelings about the experience. I also expressed my interest in doing a fuller story on his company, beyond merely piling on to all the negative words that had already been said. I wanted to know what we could learn from the Righthaven experiment. I pointed out that I was not only the subject of a copyright lawsuit and a reporter covering copyright litigation, but also a producer of copyrighted content. I, too, worry about what the future will mean for those who get paid to write in an era where controlling distribution and battling misappropriation becomes tougher and tougher.

When I eventually spoke to Gibson, I allowed him to suggest where I should take this article. His answer definitely surprised me.

“One of the questions for the article is why is it so difficult for copyright owners to hire competent copyright litigation counsel?” he said. “There’s not a lot across the country. Definitely not like personal injury lawyers. You can’t go into the phone book and find a listing. Why is it this difficult? Why isn’t there more copyright litigation?”

That’s a pretty provocative statement. Is there really a lack of good copyright attorneys in the United States? What if someone decided to steal this article? Would I be able to find an attorney to represent me if I decided to file a lawsuit?

“In writing this story, you should go out and interview attorneys out there,” he responded. “It’d be fantastic to go through real-life examples and ask ‘What would be the retainer? What would be the legal fees?’ ”

I’m beginning to see where this is heading. Does Gibson really believe that copyright litigation is an underserved market? Seems so.

At another point in our interview, he proposed that the “economic structures of law firms may not lend themselves” to picking up copyright plaintiffs. And whether that’s because of inadequate laws or because the incentives aren’t worth the spoils for media companies and their legal representation, clearly Righthaven was the vehicle that in his mind at least was attempting to solve the issue.

I put these theories to others. Stephen Zralek, a partner at Bone McAllester Norton in Nashville, Tenn., has defended a case against Righthaven and chairs the ABA’s Copyright Litigation Committee in the Section of Intellectual Property Law. He wasn’t buying it.

“There are times when worthy plaintiffs can’t afford an hourly rate and can’t convince a lawyer to take it on contingency,” Zralek says. “But it’s true that so many areas of the law are out of the reach of average Americans. I think that for someone who has a valuable work and there’s clear infringement—and they have ability to pay and they would lose more money than not litigating—the answer is simple.”

On the other hand, others like Free Ride author Levine aren’t ready to summarily dismiss Gibson’s observations. Even though Levine believes that the solution can’t be a company like Righthaven that “aggregates rights to beat people over the head,” he thinks that the cost of suing is so high and the prospect of winning statutory damages from poor bloggers is so minimal that copyright has essentially become useless. “If you are a newspaper,” he asks, “what good is it to have a right if, effectively, there is no mechanism to enforce that right?”

Assuming that’s true, and that copyright is on weary legs as a platform supporting the promotion and creation of new works, where to go from here? Some big content studios say that sweeping new copyright legislation is in order to prevent access to pirate facilitators. Others, particularly those who rallied against SOPA this past winter, believe that enforcement misses the point; they say media businesses need to embrace technological innovation, adapt their revenue models, and figure out new reasons for consumers and advertisers to buy in. And yet some in the community, stretching across some of the divides that have opened up since the DMCA was enacted, are slowly getting behind the idea that the economics of law need to be discussed. In particular, many are following discussions under way at the U.S. Copyright Office about a small claims circuit for copyright claims.

How about you, dear reader? When you have your Google moment and see something out there on the Web that seems to be stolen from you, what should happen? Is there an ethical way to handle the situation that’s both financially reasonable and sure to be effective? Or must you acknowledge that control is out of your hands these days and there’s really no recourse?

Tough questions, surely. Don’t sue me for asking.

Eriq Gardner is a freelance writer in New York City.