The William Rehnquist You Didn't Know

Almost every week, from the late 1980s until his death from thyroid cancer in 2005, U.S. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist was in touch with Herman J. Obermayer, a former editor and publisher of the Northern Virginia Sun daily newspaper. Late in their lives, after a chance encounter on a tennis court, the two became the best of friends. This unlikely association between the journalist and the justice gave Obermayer a unique window into a very private man.

Bill Rehnquist’s public demeanor and appearance were best described as unexceptional. Good-looking but not movie-star handsome, he stood out in a crowd chiefly because of his height: 6 foot 2. The wisps of hair surrounding his baldness had a brownish-rusty hue. Always careful about his diet, he never became paunchy. He wore large-lens, fashionable glasses, and his easy laugh showed a mouth full of old-fashioned gold crowns. He dressed appropriately but uninterestingly: button-down shirts, unobtrusive ties, Hush Puppies-type shoes, work pants (but never jeans) on weekends, and off-the-rack suits that he usually bought from lower-end mall haberdashers.

A hearty greeting accompanied a weak handshake. At belly-laugh movies, he had no reticence about audibly guffawing. While his lifelong back problems did not seriously compromise his posture, he was slightly pigeon-toed and walked with a discernible lope.

Bill welcomed gossip about mutual friends and colleagues. The social isolation forced on him by his exalted position meant that only rarely was he able to enjoy exchanging juicy tidbits about members of the judicial and social communities of which he was a part.

Rehnquist as a child. Photo courtesy of The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

He lived far below his means. Stock and bond investing bored him. Other than his two modest homes, at the time of his death his entire estate consisted of $708,689 in savings accounts at banks a few hundred yards from his Arlington, Va., townhouse. His neighbors were law firm associates and middle-level civil servants. Ostentation offended him.

Those who were able to pierce the hard outside shell that hid Bill Rehnquist’s character and personality discovered a quick-witted man who cherished abiding friendships, admired personal loyalty and empathized with other people’s travails. He was obsessively frugal, annoyingly punctual, endlessly curious and addicted to cigarettes.

Conservatism was a core value. It was an essential part of the prism through which Bill viewed life. Its application to politics and government was only a small portion of a larger value system. He respected tradition and order—intellectual and social, as well as political and economic. He believed that the proven and established should not be rejected until there are substantial reasons to believe that the new is superior. Our friendship would never have developed as it did if we had not shared similar conservative approaches to politics, family life, economics and ethics.

• • •

Bill’s loneliness after the death of his wife, Nan, in 1991 was apparent to anybody who saw him regularly. He did not try to hide it.

At our Sunday morning tennis games, I could tell that Saturday nights were the loneliest of the week for him. After routine greetings, he would almost always ask what my wife, Betty Nan, and I had done the previous evening. I would describe a typical suburban couple’s Saturday night (dinner with friends, neighborhood party, movies, a charity event, etc.). Bill would then sometimes tell me about a quasi-official party that sounded glamorous but that he found tedious. More often he would describe a dinner of hot dogs, canned vegetables and ice cream followed by an evening with the TV remote. (For more than a dozen years he prepared most of his own meals, but he always considered cooking a chore, rather than a creative pleasure.)

Shortly after Nan’s funeral, Bill began joining us regularly for a home-cooked dinner, usually on a weekday.

Rehnquist in the late 1940s. Photo by Lainson Studios

After dinner we often played high-spirited games of Rummikub, a game that generally follows the rules of gin rummy but is played with cubes on a table, like dominoes. Even though Bill reciprocated by periodically taking us to dinner at a local restaurant, there was an unevenness about the arrangement. One of us always had to “invite” the other. We needed a different system with no formalities.

Dinner and movies together on the weekends seemed like the obvious answer. But threesomes are not part of the natural social order. Before 1992, each of us spent Saturday nights with our spouses and occasionally with other couples. Betty Nan and I had several unmarried friends—as Bill and Nan did also—but as a rule of thumb we would meet our single friends on weekday evenings, almost never on a Saturday night.

Still, for a dozen years the Bill-Betty Nan-Obe Saturday night threesome seemed natural, appropriate, uncomplicated. Like everything else in my relationship with Bill, we approached it cautiously. For several weeks each of us, for our own reasons, had doubts about the feasibility of a regular Saturday night outing. But we soon bonded as a threesome.

• • •

Rehnquist and his wife, Nan. Photo courtesy the Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States

Bill was a frugal man. It was one of his most basic character traits. And it was one that was constantly manifesting itself—in his chambers, in restaurants, in shopping malls, at the public library, on the tennis court. His colleagues, clerks, friends and family all joked about it. They usually substituted the words tight, cheap or parsimonious for frugal. Occasionally he kidded himself about it.

My first experience with Bill’s feelings about waste came on the tennis court a few weeks after we met in 1986. Before beginning our third or fourth singles match, I followed a custom that I had long understood to be country club etiquette: I opened a new can of tennis balls.

Bill then casually asked me how often I played. After he had determined that I rarely played more than once a week, he explained that he did not like people who confused extravagance with courtesy. If the balls we had played with the previous week were not worn out, we should continue using them. After a month or two of weekly play, we should examine the balls we had used. If they showed signs of wear, then one of us should buy a new can of balls—but only if they showed obvious signs of wear. Obvious “signs of wear” to him meant there was almost no discernible fuzz on the balls. At the time I viewed this as quirky: For the cost of a can of tennis balls, why make a fuss? Only later did I realize this was a typical manifestation of his basic character trait.

At the end of a movie date we always settled accounts down to the last nickel. It did not occur to him that sometimes it might be easier to round accounts to the nearest half dollar. Since I was always the “treasurer,” he would inquire about whether I had included parking fees, coat check tips and even the one-dollar premium that is charged by most cinemas if movie tickets are reserved in advance by phone.

• • •

My involvement with Bill and the presidential election of 2000 began late in the afternoon of Nov. 6, 2000, the Monday before Election Day. Betty Nan and I had just faxed our election picks to Bill’s secretary, Janet Tramonte, and she had faxed his back to us.

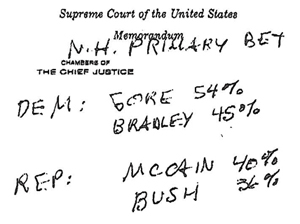

Rehnquist and Obermayer often wagered a dollar on one or two close political races.

Betty Nan, Bill and I began betting on elections shortly after the death of Bill’s wife, Nan, in 1991. In the beginning, it was simple. We each bet $1 on one or two close races, shook hands and paid off the next time we had dinner together. But in a few years, without deliberate planning, the scope of our betting expanded. The money involved remained insignificant. The wagering terms, however, became complicated. On some Election Days we each wagered a dollar on two dozen or more individual races. To add complexity and variety to our game, we changed the terms regularly. Sometimes we simply chose a winner. More often we wagered on spread, voter percentage or by what percentage each party would win in a legislature.

After our election cards grew lengthy and complicated, it became necessary to record our bets in writing. Conversation on movie dates during October often focused on how we would organize our betting cards for an upcoming election. The arrangement by which we exchanged our picks was efficient and easy. Betty Nan and I faxed our selections to Bill’s secretary and, after receiving our choices, she faxed Bill’s to us. This allowed the bettors to keep their choices secret.

I had some reticence about using the chambers of the chief justice of the United States as a betting parlor. But when I questioned Bill about it, he brushed me aside. “Janet loves being part of all this,” he explained.

After the death of Rehnquist’s wife, he and the Obermayers often went out socially as a threesome. Photo by Warren Mattox, Mattox Photography

The day before the election, Bill bet George W. Bush would trounce Al Gore by 320 to 218 electoral votes. While Betty Nan and I also picked Bush, we thought he would win by substantially smaller margins: I bet 292 to 246; Betty Nan bet 280 to 258.

Bill’s final Electoral College numbers do not tell the full story. A re-view of his longhand worksheet shows that between the time he originally prepared his betting entry (Sunday evening) and the time it was faxed to our home (Monday afternoon) he changed his mind about the races in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania and Michigan. His last-minute changes resulted in his adding 15 electoral votes to Bush’s total. Bill rarely, if ever, switched his faxed bets impetuously or on the basis of his personal preference: His betting card confirms that as the moment of truth grew closer, his belief in a Republican sweep grew stronger.

While he was dead wrong in switching his bets on Pennsylvania and Michigan from Gore to Bush, the tally in Wisconsin was almost as close as the one in Florida. Gore carried Wisconsin by 5,708 votes.

• • •

On Nov. 21, Florida’s Supreme Court ruled in Gore’s favor. On the same day, Bill faxed the following letter to Betty Nan and me:

Dear Obie and Betty Nan:

It now appears remotely possible that the Florida election case might come to our court. I therefore feel obliged to cancel all my election bets in any way dependent on the Florida vote. I hope you will agree to let me do this.

Sincerely,

Bill Rehnquist

Needless to say, we did.

• • •

On Saturday, Dec. 16, four days after the Bush v. Gore decision, our movie threesome saw Bounce, a character drama with a romantic twist. It was not the genre we most preferred, but it was playing at an Arlington cineplex where we could park in a multilevel garage and enter the movie theater without walking on the street. It was the first and only time during our friendship that Bill was concerned about being harassed in public. After the movie, over dinner in the Obermayer kitchen, Bill explained that he was concerned about subjecting us to loud, hateful speech and obscenities. He said he feared that we might get hurt if someone decided to hurl a rock at him. But as he did throughout our friendship, he traveled without any security detail.

• • •

At dinner that night, Bill and I discussed what would have been the pros and cons of filming the oral arguments in his court five days earlier. Almost every major media organization in the world was signatory to a petition to allow TV coverage. While the justices turned down the request for live TV coverage, they did allow an audio feed and a typed transcript of Bush v. Gore to be released a few minutes after the arguments ended.

That evening Bill told me that he had begun wondering whether the intensity of the passions aroused by the court’s involvement in the presidential election justified approaching live TV coverage with even more skepticism. He had a new concern, he said. It was one I had never thought about. I do not know whether the notion had been buried in his psyche for a long time, or if he had learned about it from one of his colleagues when they discussed the hateful and vicious way they were being described in the press.

His new reason for opposing videotaping the Supreme Court was that after several years of taping oral arguments, hundreds of tapes would be in the public domain. They could easily be aggregated and manipulated to demean and denigrate particular justices or to diminish the stature and legitimacy of the Supreme Court itself. A TV producer could easily cobble together a program in which a group of justices were shown repeatedly picking their noses, cleaning their teeth, dozing off, scratching their behinds, popping pills, doodling erotic obscenities, winking at old friends or asking foolish questions during an oral argument. In the course of a decade or two on the Supreme Court bench, it was inevitable that a sizable number of unflattering, silly and demeaning poses would have been recorded for each justice. Images gathered to advance the people’s right to know could easily be used as raw material for editorializing, propagandizing and creating polemical attacks on the court as an institution. A talented video editor could likely enlarge a justice’s doodling and discern, as well as memorialize, never-articulated thoughts about lawyers, colleagues, cases—maybe even domestic or medical problems. Unedited videotapes in the public domain have a potential for mischief that has rarely been discussed. I had never thought about it before our dinner.

Rehnquist, 1971.

Photo: Bettman/Corbis

Bill saw this post-Bush v. Gore scenario as a threat to the Supreme Court’s stature and status. I acknowledged his main point that the existence of a film library of court proceedings would allow clever editors to manipulate tapes to make points that had nothing to do with news gathering. Like all aggregations of knowledge, a video library can be used for good or ill. But I still believed the advantage of making videos outweighed the disadvantages.

• • •

Bill was probably addicted to cigarettes. They were very important to him. During the two decades of our friendship, I do not recall any time when he was trying to break, or even curtail, his tobacco dependence. While he was not furtive or secretive about his habit, he was not in your face about it, either. When the three of us had dinner together at our home or at a restaurant, he always had a cigarette after the meal. After we attended a movie, he occasionally had a smoke with his light beer before dinner.

But if Bill was at a dinner party with several couples around the table, he did not light up until someone else did. If no one else had an after-dinner cigarette, he did not have one, either. However, if he did not have a smoke at the table, or soon afterward, he usually left for home shortly after the meal. He profusely apologized to his hostess. He explained that he was “very tired” and had a lot of reading to do for the next day’s conference or oral arguments, or whatever. “Very tired” was code. He never hinted that he would have enjoyed continuing the after-dinner conversation, if he could have smoked a cigarette without appearing to be impolite or breaching an evolving community standard. This carried over to restaurants. In the smoking section, we relaxed. If we were seated in a nonsmoking area, the end of the evening was rushed.

I often speculated as to why a man who was smart, disciplined, intellectually focused and strong-willed could not break the tobacco habit. Whenever I brought up the subject, he explained that he knew he could quit. As a matter of fact, he said he had gone cold turkey for extended periods several times in his life. But he greatly enjoyed cigarettes. And he knowingly accepted the trade-offs. Several times he explained his addiction in an idiom he particularly liked: “Let’s just say I am an informed bettor.”

• • •

Bill’s near obsession about punctuality affected most of his relationships—with colleagues, subordinates and friends. It was hard to ignore, and it was often annoying. Bill was always on time. And he expected everybody with whom he had any kind of dealings to do likewise. No exceptions.

If I agreed to pick him up at 4:10 p.m. to go to a movie and I arrived at 4:12 p.m., he would be pacing up and down the sidewalk or sitting on the stoop and scowling. On all but the coldest days of winter, if I was a few minutes late, he gave me his unspoken punctuality message. If I arrived at 4:05 p.m., I parked in front of his townhouse. Then at 4:10 p.m. (exactly!) he would come bounding down the steps. If we planned to watch a football game (usually at my house because I had a larger TV screen) at 1 p.m., he always rang the doorbell between 12:58 p.m. and 1 p.m. If he arrived in my neighborhood a few minutes early, he parked unobtrusively on a nearby street. Then he rang the doorbell at what he perceived as the proper time.

Rehnquist’s townhouse in Arlington, Va.

Photo: courtesy of Herman Obermayer

• • •

When the newspapers said that Bill was recuperating after his thyroid operation at his “suburban Virginia home,” it created the comforting image of genteel, elegant surroundings. But the reality was different.

After his surgery, Bill was too weak to climb the eight steps lead-ing to his front door, so he lived in the basement of his Arlington townhouse. This area included a tiny bedroom and a former recreation room with a wet bar and calendar-type art on the walls.

While he greeted his friends, reviewed briefs, watched television and slept in his townhouse, he never again sat at his dining room table, slept in his own bed, ate meals prepared in his kitchen or entertained family and friends in his tastefully decorated living room.

Only with this arrangement could he continue to live in his own home. The basement recreation room in which Bill spent almost all of his waking hours opened onto a patio that allowed wheelchair access. The room was converted into a parlor/office/TV room. It was furnished with a large recliner in front of a television (where he spent most of his last days), an old sofa, a card table and assorted chairs. The adjacent small room where he slept did not have a bathroom en suite. Before his illness, the basement recreation room had been used to host card games and to greet guests going to parties on the patio. During his convalescence, the wet bar facilitated the work of the medical professionals who cared for him and lived in the rest of the house.

• • •

Before Bill was buried, President Bush had named his successor. At the apex of government, succession had been timely, orderly and seamless. Still, Bill’s death created a great void at the Supreme Court. The old order had passed. John G. Roberts Jr., the new chief justice, brought with him the perspectives and insights of a new generation. He was born in 1955, the same year as Bill’s son, Jim, a decade after the end of World War II.

Bill’s perspective could not be replicated. The knowledge and life experiences he brought to the job were his—and his alone. His outlook was unique to his generation, to his time in history.

Bill and I shared that generational perspective. Like most boys who graduated from high school in 1942, while still teenagers we had already acquired a deep-seated and personal understanding of the power of government. And we dreaded it. We knew that shortly after our 18th birthdays, the government of the United States of America—the government of the democracy that we loved—could take away our liberty.

Rehnquist (left) clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson (center) druing the court’s 1952-1953 term.

Photo: Franz Janzen, Collection of the Supreme Court

We knew that after a few months’ training, a low-level military bureaucrat could send us on a new assignment. It might be for more training.

But it also might be to some contested barricade where our deaths were likely, probably inevitable. This youthful experience with government power in the United States affected our thinking the rest of our lives. Understanding this is part of fathoming Bill.

Bill’s judicial opinions should be appraised on their merits—legal, social and ethical. That is someone else’s job, an ongoing, evolving job. Yet no product of the human brain was created in total isolation. Often those products can best be understood in the larger context of the life that created them.

Herman Obermayer photo by Brian Trompeter/Sun Gazette Newspapers