Unsettling Science: Experts Are Still Debating Whether Shaken Baby Syndrome Exists

Audrey Edmunds, now 50: “I’m not the monster they made me out to be.” Photo by Keri Pickett

Is Audrey Edmunds an otherwise kind and caring wife, mother and neighborhood child care provider who snapped into a homicidal rage one day under the stress of caring for a sick baby?

Or is she an innocent woman who spent 11 years behind bars for a horrific crime she not only didn’t commit, but that may not have even been a crime?

You decide. We can’t. And neither, apparently, can the courts or the scientific community.

Fifteen years ago, Edmunds, then a 35-year-old stay-at-home mom, was convicted of reckless homicide in the 1995 shaking death of a neighbor couple’s infant daughter. She was sentenced to 18 years in prison.

In 2008, however, a Wisconsin appeals court granted her a new trial on the grounds that a shift in mainstream medical opinion as to the cause of the girl’s injuries now casts doubt on Edmunds’ guilt.

Prosecutors subsequently dismissed the case against Edmunds—not because they think she is innocent but to spare the victim’s parents the agony of having to revisit their daughter’s death.

Three years later, Edmunds’ culpability remains a hotly contested topic of conversation in criminal justice circles. And her case has reignited a fierce debate in the forensic community over the science behind what’s called shaken baby syndrome.

To be sure, the vast majority of doctors still regard it as a valid and reliable diagnosis, one whose scientific basis has been proven time and time again by decades of peer-reviewed research, clinical experience and caregiver confessions.

But a small and apparently growing number of forensic experts have begun to question many of the assumptions upon which the diagnosis rests—like whether shaking alone can produce the kind of traumatic head injuries attributed to SBS in the absence of other injuries, like a broken neck, or whether a child who has been shaken violently would immediately be rendered unconscious.

The decision marks the first time that an appeals court has questioned the scientific basis for a shaken baby conviction, and some hope the Wisconsin ruling will lead to a systematic court review of the evidence in other shaken baby cases, or even an independent examination of the underlying science by some neutral third party like the National Academy of Sciences.

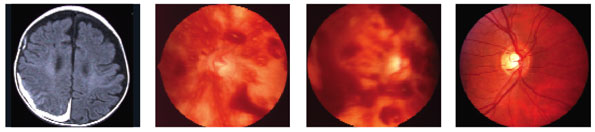

Left to right: A brain MRI showing blood—indicated by the white crescent—between the skull and brain of a baby alleged to have suffered a violent shaking, photos of the right and left retinas of the same baby, a normal retina. Photo courtesy of Jonathan Trobe, MD, University of Michigan Medical System.

Shaken baby syndrome is a term coined in the early 1970s to describe what adherents contend is a characteristic set of head injuries found in infants who have been subjected to violent shaking: swelling of the brain, bleeding around the brain and bleeding in the retinas.

The theory was first espoused by a pair of pediatric specialists as a possible cause of the otherwise unexplained head injuries sometimes seen in infants with no visible signs of physical abuse. It quickly took root in the medical community.

Before long, SBS became widely accepted as a clinical diagnosis for head injuries inflicted on small children. And a nationwide educational campaign to alert the public to the dangers of shaking was launched.

In fact, SBS is now so firmly ingrained in the public consciousness that the World Health Organization has a diagnostic classification for it; the American Board of Pediatrics offers a subspecialty in it; and last year, for the fifth year in a row, the U.S. Senate designated the third week in April as National Shaken Baby Syndrome Awareness Week.

To this day, there is widespread consensus among medical professionals that shaking a baby is dangerous and often lethal. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Ophthalmology and the National Association of Medical Examiners have all issued position papers embracing the theory, although the NAME paper, which was published despite failing peer review, was later withdrawn. The Centers for Dis ease Control and Prevention publishes SBS prevention guides for public health departments and community organizations. And several states, including Ohio, New York and Texas, require prospective parents and child care providers to learn about the perils of shaking.

An estimated 1,200 to 1,400 children are injured each year by shaking, about one-quarter of them fatally, according to the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, a nonprofit organization offering SBS prevention and training programs. The actual number of victims may be much higher, it says, because many such cases are misdiagnosed or go undetected.

But a growing chorus of critics says the entire theory rests on an uncertain scientific footing that continues to erode under the weight of scientific scrutiny, raising the specter that hundreds if not thousands of innocent people—parents, grandparents, baby sitters, nannies, boy friends—have faced criminal charges and even been imprisoned in the past three decades for crimes they may not have committed.

No one apparently keeps count of shaken baby prosecutions, though some experts estimate that about 200 people a year are convicted of shaking-related offenses based on the number of reported appeals. While some of those cases include corroborating medical evidence of abuse, such as cuts, bruises, burns or broken bones, others do not. And though some of the accused have admitted their guilt, others have steadfastly maintained their innocence. So Edmunds’ case was, in many respects, a typical one.

Because she loved kids—by 1995 she had two of her own and was pregnant with a third—and wanted to help out her neighbors, Edmunds quit her secretarial job and started caring for a few children in her home in the Madison, Wis., area. One of her newest charges was 7-month-old Natalie Beard.

Natalie, by all accounts a fussy baby, was particularly irritable on the day in question, Edmunds recalls. She tried to get the girl to eat, but Natalie refused, so she placed her in a car seat in the master bedroom and propped a bottle of formula in her mouth while she got her oldest daughter ready for preschool. She checked on Natalie once and everything seemed fine. But when she went back a second time, the girl was limp and unresponsive. Natalie was airlifted to a nearby hospital, where she died later that night.

Nobody saw Edmunds shake Natalie. There were no external signs of injury on the girl’s body. And Edmunds swore up and down she hadn’t done anything to harm the baby. But the doctors who treated Natalie concluded that she died from brain trauma caused by a violent shaking or a shaking with impact, citing among other things severe brain and eye damage peculiar to shaking and evidence of an impact injury to the girl’s scalp.

Edmunds defended herself as best she could. Her lawyer, Stephen Hurley, couldn’t find any experts who didn’t think Natalie had been subjected to a violent shaking, though he found one doctor who thought the girl had been shaken before she was dropped off at Edmunds’ home that morning. And the lawyer concedes that Edmunds made a terrible witness while testifying in her own defense.

“She was like a deer in the headlights on cross-examination,” he says. “I think that really hurt her.”

An army of prosecution experts testified that Natalie exhibited all the telltale signs of a severe shaking. This was no accidental shaking either, they testified, but one that was the equivalent of a fall from a two- or three-story building, or a car crash at 25 to 30 mph. And Edmunds must have done it, they insisted, because Natalie’s injuries were so severe she would have lost consciousness as soon as she was shaken.

The prosecutors also depicted the defendant as some kind of Jekyll and Hyde figure who reacted violently under the pressure of caring for a sick baby while five months pregnant and in the process of moving. She was convicted and sentenced to 18 years in prison.

Keith Findley, a law professor and co-director of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, got involved in Edmunds’ case after realizing that the medical community could not agree on whether Natalie Beard’s injuries were caused by shaking alone or other factors were involved. Photo by James Schnepf.

Edmunds’ first appeal, in 1999, went nowhere. But her luck changed in 2003 when the Wisconsin Innocence Project took an interest in her case.

The project’s co-director, Keith Findley, who teaches law at the University of Wisconsin, doesn’t remember exactly how he got involved in the case, but he does recall that both Edmunds’ trial and appellate lawyers had been deeply troubled by her conviction and were convinced of her innocence.

Findley knew very little about the subject at the time, other than what he had read about the 1997 Boston trial of British au pair Louise Woodward in the apparent shaking death of 8-month-old Matthew Eappen, the first high-profile courtroom battle over a shaken baby diagnosis. (A jury ultimately convicted Woodward of second-degree murder, but the judge reduced her conviction to involuntary manslaughter and sentenced her to time served.)

But Findley soon realized there were already raging debates in the medical community about whether shaking alone could produce the head injuries Natalie Beard suffered; whether such injuries could be due to other causes, both natural and inflicted; and whether a child with the kind of injuries Natalie had could remain lucid for hours or even days before dying or becoming noticeably impaired.

Then he discovered that one of the state’s key witnesses—Robert Huntington III, the pathologist who had done the autopsy on Natalie—had written a letter in a medical journal contradicting his testimony in the case against Edmunds.

Huntington had testified at Edmunds’ trial that it was “highly probable” Natalie’s injuries were sustained while she was in Edmunds’ care. But in his letter he wrote about a 1999 case he observed in which a child with head injuries similar to Natalie’s remained lucid in a hospital for more than 15 hours before she died.

When Findley contacted Huntington and told him why he was calling, Findley says, Huntington replied, “Oh, Audrey Edmunds. What are we going to do about that?”

Armed with that information, the defense prepared a motion for a new trial on the grounds that medical research developed in the decade since her 1996 trial constituted new evidence establishing a reasonable probability that a different result would be reached the second time around.

At a hearing on that motion, Huntington testified that he was no longer sure that Natalie had been shaken or that her injuries had been inflicted while she was in Edmunds’ care. Other defense experts testified that research advances in the previous 10 years had undermined the scientific basis for SBS and legitimized the views of critics once regarded as being on the fringe.

Prosecutors, however, contended that the case against Edmunds was even stronger than it had been in 1996, saying the intervening years of study and research had only reaffirmed the cause and timing of Natalie’s death. They argued that none of the six defense experts who testified on Edmunds’ behalf could provide an alternative explanation for Natalie’s injuries. They said the evidence the defense cited as new—whether shaking alone can cause such injuries and whether a child with such injuries could experience a lucid interval—had been the subject of an ongoing debate in the medical community that began long before her first trial. And they claimed it didn’t matter whether shaking alone can produce the kinds of injuries Natalie sustained because the state had also produced evidence of an impact injury to her scalp.

A Texas Child Protective Services specialist poses with a doll used for educating about the danger of shaken baby syndrome. Photo by Tyler Morning Telegraph, David Branch.

The trial court judge found that both sides had presented credible evidence. But he denied the defendant’s motion on the grounds that the state’s evidence was more persuasive.

However, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals reversed, saying that a “significant and legitimate debate” had developed in the medical community in the previous 10 years as to whether babies can be fatally injured through shaking alone, whether a baby with a traumatic head injury can experience a significant lucid interval prior to death, and whether other causes may mimic the symptoms traditionally associated with shaken baby syndrome. And those are issues for a jury, not a judge, to decide, the court said.

“The newly discovered evidence in this case shows that there has been a shift in mainstream medical opinion since the time of Edmunds’ trial as to the causes of the types of trauma Natalie exhibited,” the court wrote, noting that the debate reflects “a fierce disagreement between forensic pathologists who now question whether the symptoms Natalie displayed indicate intentional head trauma, and pediatricians who largely adhere to the science as presented at Edmunds’ trial.”

The decision prompted DePaul University law professor Deborah Tuerkheimer, a former child abuse prosecutor in Manhattan, to take a closer look at the science underlying the syndrome—which she, to put it mildly, found wanting.

Tuerkheimer published her findings in a 2009 Washington University Law Review article called “The Next Innocence Project: Shaken Baby Syndrome and the Criminal Courts.” She concluded that scientific advances in the past two decades have cast doubt on an entire category of SBS defendants—namely those convicted of shaking-related crimes based solely on the three key symptoms known as the “diagnostic triad.”

“While we cannot know how many convictions are ‘unsafe’ without systematic case review, a comparison of the problematic category of SBS convictions to DNA —and other mass exonerations—reveals that this injustice is commensurate with any seen in the criminal justice arena to date,” she wrote.

With the publication of Tuerkheimer’s article, an already divided scientific community appears to have become even more polarized.

Defenders of the SBS diagnosis complain that she leaves the impression that thousands of innocent people are sitting in prison due to a flawed scientific diagnosis. But critics of the SBS diagnosis, already galvanized by their legal victory in Edmunds’ case, view Tuerkheimer’s analysis as vindication of their complaint: That the research basis for shaken baby syndrome was flawed from the start.

The origins of SBS date back to 1968, when a prominent neurosurgeon conducted an experiment on rhesus monkeys to see whether brain and neck injuries would result from the whiplash forces of a simulated 40 mph rear-end car crash. The monkeys were strapped into a sled mounted on a 20-foot-long track, leaving their heads free to rotate, and the sled was struck from behind with a mechanical piston.

About a third of the monkeys suffered cerebral hemorrhages. Eleven of them also suffered injuries to the brain stem or cervical cord.

The experiment had nothing to do with babies or shaking. But in the early 1970s, two pediatric specialists, writing separately, pointed to the results as evidence for the proposition that a violent shaking with out impact, which one of them dubbed “the whip-lash shaken infant syndrome,” could cause permanent brain damage and mental retardation in infants and small children.

Ever since, critics say, the mainstream medical community has held to the belief that the presence of subdural bleeding, retinal hemorrhages and brain swelling in a child with no other injuries suggestive of an accident or abuse must have been shaken. And that the person with the child when he or she lost consciousness must have done it.

But those beliefs have been steadily undermined by subsequent research showing just the opposite, critics say.

The first big blow to conventional SBS wisdom was struck in 1987. That’s when a neurosurgery resident at the University of Pennsylvania, working with a group of biomechanical engineering students, devised an experiment designed to compare the forces generated by a violent shaking with established injury thresholds. To do so, they created models of 1-month-old babies equipped with sensors to measure acceleration, which were then shaken and slammed against both padded and unpadded surfaces.

Researchers found they couldn’t shake the dummies hard enough to generate the kind of force known to cause even a mild concussion. In fact, the most force they could muster was about one-fiftieth the amount of force generated by dropping the dummies onto a padded surface.

Another big blow to mainstream medical opinion on the subject came in 1998, when a forensic pathologist at East Carolina University School of Medicine studied the interval between injury and the onset of symptoms in 76 alleged child-abuse head injury deaths. In one-quarter of the cases, the interval was more than 24 hours; and, in four cases, it was more than 72 hours, apparently contradicting the conventional belief that a child with traumatic head injuries would be immediately symptomatic.

Further research in the past decade or so has shown that there are many other causes of the three key symptoms associated with SBS, including: short-distance falls, congenital malformations, genetic and metabolic disorders, various forms of childhood strokes, accidental injuries, infectious diseases, poisons, medical and surgical complications, and autoimmune conditions. And the list, now two pages long, continues to grow.

Some critics question the very existence of shaken baby syndrome. “There’s no such thing,” says retired forensic pathologist John Plunkett of Welch, Minn., an early critic of the diagnosis who has gone on to became a leading defense expert in shaken baby cases. “It doesn’t exist.”

Thomas L. Bohan, a lawyer and physicist who is a past president of the American Academy of Forensic Sciences, says he doesn’t know of a single physicist or biomechanical engineer who supports what he calls “this cockamamie notion” of shaken baby syndrome.

“It’s not something I can disprove,” he says, “but I can say that there’s no evidence to support it, and that every attempt to prove it has failed.”

In 2009, during his year as academy president, Bohan convened a blue-ribbon panel to review four areas of forensic science about which serious questions have been raised, including SBS.

The panel called for an independent investigation of the science behind the theory, to be undertaken by a qualified scientific organization amenable to both sides, which it said was “particularly crucial,” given the number of respected doctors on each side of the issue and the number of people who are sentenced to long prison terms each year for shaking-related offenses.

Another critic, Cyril Wecht, a lawyer and former Allegheny County, Pa., coroner, wouldn’t go so far as to suggest that SBS doesn’t exist. But he believes it’s one of the most overdiagnosed and misunderstood concepts in forensic science.

So much so that he wouldn’t want his four children or 11 grandchildren to baby-sit someone else’s kids.

British au pair Louise Woodward sits with her attorney, Barry Scheck, during prosecution testimony in 1997. Woodward was accused in the alleged extreme-force-injury death of infant Matthew Eappen. Photo by AP/Bizuayehu Tesfaye.

“When you come into a hospital emergency room in America today with an injured child, it’s automatically assumed you’re responsible for whatever happened until you prove otherwise,” he says.

Yet defenders insist that the scientific basis for SBS is not only sound but getting stronger every day.

Dr. Robert Block, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, says there are now decades of ever-accumulating research, clinical observations, individual case reports and other data showing that babies can be injured through shaking, impact or a combination of the two.

Critics “say you can’t shake a baby hard enough to hurt it,” he says, “which they themselves would never do because they know damn well they’d end up with a dead baby or one with significant neurological injuries if they did.”

Block and other defenders say the only controversy over SBS in the medical community is the one that has been created out of whole cloth by a small group of defense-oriented experts who ignore the known science, discount the clinical experience of doctors who treat injured kids every day, and excuse the voluminous confessional literature in an effort to sow confusion and create doubt. They call them denialists.

Denialists, to these SBS defenders, typically use rhetoric to give an appearance of legitimate and unresolved debate about matters long considered to be settled by the medical or scientific communities. Or they are simply inflexible, like those who insist—despite all evidence to the contrary—that childhood vaccinations can be linked to autism and mental retardation.

Dr. Alex Levin, a pediatric ophthalmologist in Phila delphia who studies the eye manifestations of child abuse, says the only real way to find out whether SBS exists is to shake a baby and see what happens. But short of that, all available evidence—computer models; animal models; studies of children with diseases that mimic some of the symptoms of shaking; perpetrator confessions; and child abuse victims, both living and dead—shows that babies do get injured and die at the hands of otherwise well-meaning and loving caretakers who momentarily lose their temper.

“Shaken baby syndrome is real,” he says.

Levin, who testified for the state in Edmunds’ appeal, was reluctant to discuss his testimony without reviewing his notes. But prosecutors say he testified that Natalie sustained a type of severe retinal damage that indicates either a violent shaking or a crushing injury, about which there had been no evidence.

SBS defenders also say the so-called triad of symptoms—as often described by critics—are never the sole basis for a shaken baby prosecution but only the starting point in a diagnostic process. That process includes the medical findings, X-rays, the baby’s prior medical history, law enforcement and child welfare reports, interviews with the caregiver, and various tests to rule out other possible causes of the child’s condition before a final diagnosis is made.

“The medical findings are not presented in a vacuum,” says Leigh Bishop, a senior trial attorney in the special victims bureau of the Queens County, N.Y., district attorney’s office. “Juries base their decisions on all of the facts and circumstances of a case, not on some far-fetched defense claim that a short fall, a vaccine, meningitis, the West Nile virus or CPR may have caused the child’s injuries.”

Defenders concede that there are other potential causes for each of the symptoms associated with SBS, but say there is nothing else that mimics the symptoms in all of its manifestations. And while they acknowledge that people with certain types of brain injuries may experience a lucid interval before the onset of symptoms, they say that’s not the case in babies with the kind of injuries characteristic of a violent shaking.

“It’s like pulling a plug out of the wall,” Bishop says. “Once the plug is pulled, the lights are off.”

SBS defenders also discount the significance of the decision in Edmunds’ case.

“It’s one opinion by one court,” says Randell Alexander, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Florida in Jacksonville and director of the state’s child protection team. “There are plenty of other courts that see it differently.”

Moreover, they suggest that the legal system facilitates irresponsible expert testimony, which they claim was the case in Edmunds’ appeal. They argue that the Wisconsin court allowed the defense great leeway: setting a low bar for the qualification of expert witnesses; allowing experts to offer opinions without stating a basis; and permitting experts to rely on inadmissible evidence, including hearsay.

And both sides say the courts often seem ill-equipped to exercise control over the admissibility of complex medical evidence.

“Legitimate controversy exists in some areas of the medical research, and reasonable medical opinions may differ over select issues,” says Brian Holmgren, a veteran child abuse prosecutor in Nashville, Tenn., who teaches other prosecutors how to handle such cases. “But seldom do these controversies reach the core science of shaken baby syndrome or attack the legitimacy of the medical criteria used to diagnose this form of child abuse.”

In the wake of the decision in Edmunds’ case, a few other courts have followed suit. But those cases are the rare exceptions. Most shaken baby convictions have not been revisited. And new cases are being prosecuted every day.

That’s why critics of SBS are calling for an objective review of the evidence on both sides, to be conducted by a credible scientific organization like the National Academy of Sciences, which published a comprehensive report on the state of forensic science in the U.S. in 2009.

Such a study is not without precedent. In 2005, Great Britain’s attorney general, Lord Goldsmith, ordered a review of 88 shaken baby cases after an appeals court had ruled that triad-only cases “cannot automatically or necessarily” lead to the conclusion that an infant has been shaken. The review identified three convictions that warranted revisiting, in addition to nine others that had previously been identified as suspect.

And in 2007, the Canadian province of Ontario convened an inquiry into 48 shaken baby convictions. The vast majority of those convictions, 44 of them, were found to be of no concern. The remaining four have been referred to the attorney general for further possible action.

Many SBS defenders say they would welcome such a study. But some suggest it would be a complete waste of time.

“To do such a study suggests there’s an issue to be dealt with,” Alexander says. “And I don’t think there are any issues to be dealt with.”

Meanwhile, Edmunds, now 50, maintains her innocence. She says she would never do anything to hurt a child. And she can’t believe that anybody could think she would.

Assistant District Attorney Shelly Rusch says all the evidence in Natalie’s death indicates a violent shaking or other “high-energy traumatic event.” Photo by James Schnepf.

“I’m not the monster they made me out to be,” she says.

Edmunds, whose husband divorced her while she was in prison, moved to the Minneapolis area after her release, where she rents a room in a friend’s house and works in a convenience store until something better comes along.

Though she’s still angry about what happened to her, she’s determined not to be bitter.

“Bitterness will destroy you,” she says.

But Dane County Assistant District Attorney Shelly Rusch—who represented the state in Edmunds’ appeal —still believes that, in a fit of rage, Edmunds killed Natalie.

Rusch says that all of the medical evidence points to either a violent shaking or some other “high-energy traumatic event” like a car crash, which didn’t happen.

“Babies don’t just die for no reason,” she says.