We Need to Talk: Sponsors of Judicial Recusal Proposal Seek More Input Before Going to House

As the Nov. 14 deadline for filing resolutions with the ABA House of Delegates approached, two ABA committees were finalizing a proposal on judicial disqualification issues relating to spending in judicial election or retention campaigns. The plan was to submit the resolution and supporting report by the deadline so that the association’s policymaking body could consider it in February at the 2013 midyear meeting in Dallas.

But now it looks like the sponsors will have to move on to Plan B. They decided to hold off on bringing their resolution to the House in February so that further discussions can be held with other interested entities, said Myles V. Lynk, who chairs the Standing Committee on Professional Discipline, which worked with the Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility to draft the resolution and report.

The other interested entities include the Judicial Division, the Tort Trial and Insurance Practice Section, and the Standing Committee on Judicial Independence.

That means the resolution won’t go to the House until at least the 2013 annual meeting. But Lynk, a law professor at Arizona State University, says the wait will be beneficial.

“Obviously, we take their views very seriously, and we want to work with them,” said Lynk during an interview with the ABA Journal shortly before the House filing deadline expired. “Our goal is that, when we come to the House, the most interested parties have been able to express their views and we’ve been able to consider them.”

The issue of judicial disqualification, or recusal, stemming from campaign contributions is not about to go away anytime soon. Some form of judicial election occurs in 37 states. And if initial findings on spending in campaigns at the state level in the November elections is any indication, the issue is likely to intensify.

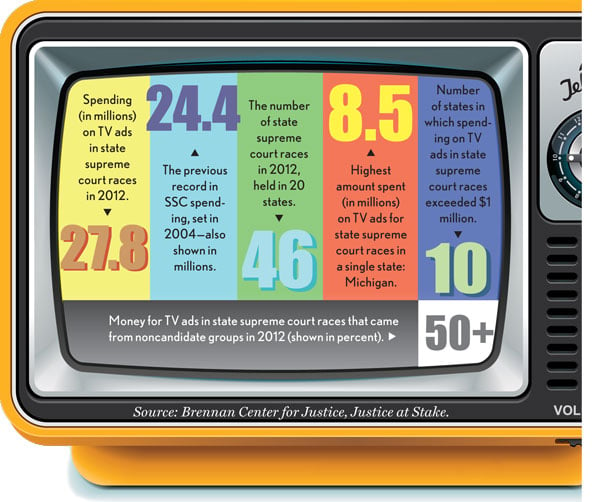

Spending on television ads in state supreme court races during 2012 totaled an estimated $27.8 million, an all-time high, according to a report issued Nov. 7—the day after the elections—by the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law and Justice at Stake, a Washington, D.C.-based nonpartisan partnership of groups working for fair and impartial courts.

‘MILLION-DOLLAR SLUGFESTS’

A disturbing aspect of the financial arms race is that it is getting harder to tell where the money is coming from, say the Brennan Center and Justice at Stake. “Political parties and independent groups dominated this year’s races, in many cases relying on secret money that does not appear in campaign finance disclosure filings,” states their report. “More than 50 percent of all TV ads came from noncandidate groups, compared with roughly 30 percent in 2010.”

The good news is that, in many cases, judges fended off political attacks as voters rejected attempts to inject politics into judicial elections and retention campaigns, says Adam Skaggs, senior counsel in the Brennan Center’s Democracy Program.

But many judicial campaigns “involved highly political, expensive efforts to oust qualified jurists,” he says. “Turning back those attempts costs a lot. … In many instances, we saw million-dollar slugfests.”

The U.S. Supreme Court has conveyed mixed messages in two key decisions about judicial disqualifications and campaign contributions. In 2009’s Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., the court ruled that the refusal of a West Virginia Supreme Court justice to grant a motion that he be disqualified to hear a case in which the CEO of one of the parties had spent some $3 million to elect the justice in 2004 created a “serious, objective risk of actual bias” that did not stand up to constitutional scrutiny. The court urged states that hold judicial elections to adopt stricter rules for disqualification to help offset the influx of money into elections.

But in 2010, the high court ruled in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that limits on campaign spending by groups such as corporations and unions are unconstitutional under the First Amendment.

“Together, Caperton and Citizens United foreshadow an increase in the number and frequency of disqualification motions, because large corporations and labor unions may now make unlimited expenditures not only in general elections but in judicial elections as well,” stated the Standing Committee on Judicial Independence in a report supporting its resolution urging that the states adopt clear procedures for judicial disqualification and disclosure requirements for contributions to judicial campaigns. “The mere possibility that a vast influx of additional campaign money might enter the latter arena, which already in the past decade has been saturated with unprecedented campaign support, virulent attack ads and concomitant diminution in public respect for state judiciaries, makes tighter controls over disqualification imperative.”

The resolution, adopted by the House in August 2011, also invited the ethics and discipline committees to consider, on an expedited basis, “what amendments, if any, should be made to the ABA Model Code of Judicial Conduct or to the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct to provide necessary additional guidance to the states on disclosure requirements and standards for judicial disqualification.” The committees did just that and issued the latest version of their work product Oct. 16 for comment by other groups.

JUST SAY KNOW

The committees’ draft resolution (PDF) focuses on Rule 2.11 of the Model Code of Judicial Conduct, which addresses judicial disqualifications. The current version of Rule 2.11(A)(4) directs that a judge “shall disqualify himself or herself in any proceeding in which the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned” because the judge knows or learns by means of a timely motion that a party, a party’s lawyer or the firm of a party’s lawyer has made contributions to the judge’s campaign in a specified aggregate amount over a certain number of years. The rule defers to the states to determine the aggregate amount and time period for the contributions.

In a memo (PDF) accompanying the draft resolution, Lynk and Paula J. Frederick, chair of the ethics committee, assert that the amendments envisioned by their committees keep Rule 2.11 essentially intact except for a minor change to Paragraph (A)(4) and a new comment seeking to define “aggregate contributions” more precisely. (Frederick is general counsel to the State Bar of Georgia.)

The proposed new language would apply Rule 2.11(A)(4) to contributions that are made both to support a judge’s campaign and those in opposition to the judge.

But the Judicial Division and TIPS have expressed concerns that the language change may carry more weight than its proponents think.

“Right now, it is a fairly minor change, but we think it misses some key issues,” says Robert S. Peck, a TIPS representative in the House. The problem is that the new language puts the onus on judges to figure out not only where their financial support came from in an election campaign, but to identify the sources of money being spent in opposition to them, says Peck, who is president of the Center for Constitutional Litigation in Washington, D.C.

The division shares similar concerns, says its chair, William D. Missouri. “A judge has no way of knowing who made contributions in his or her campaign,” says the retired state circuit court judge in Upper Marlboro, Md. “It would require a judge to expend tremendous time and effort.” The division also suggests that rule-making relating to disqualifications should be made primarily at the state level, he says. “We’re not asking for a new template.”

Missouri, along with others involved in the renewed discussions about the draft resolution, says he expects those discussions to be productive. “This is not contentious,” he says. “Our desire is that we sit down and come together.”

Shutterstock.com