A Trove of Historic Jazz Recordings has Found a Home in Harlem, But You Can’t Hear Them

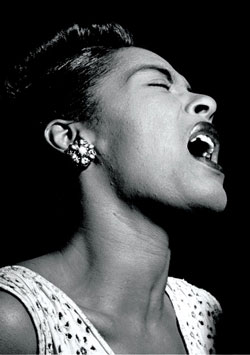

Photo of Billie Holiday courtesy of William P. Gottlieb Collection, Library of Congress

The swing era lasted barely a decade—roughly the mid-1930s until the end of World War II—but it was a golden age for jazz.

It was the only time that jazz dominated American popular music. Legendary musicians who had helped invent the music—the likes of Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, Count Basie, Teddy Wilson, Lester Young, Bunny Berigan and Coleman Hawkins—still were in their prime. And they could be heard everywhere: swank hotel ballrooms, homecoming dances on college campuses, radio programs—but especially at cramped, smoky nightclubs in such musical hotbeds as Chicago, Kansas City and New York City. In those clubs, jazz musicians honed their craft during lengthy jam sessions, where a player might improvise on chorus after chorus of standards like George Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm,” or on their own compositions or blues riffs made up on the stand.

But the only people who got to hear their jazz heroes stretch out and work through new musical ideas in those impromptu blowing sessions were those sitting in the audience. In those days, technology limited recordings to a window of only about three minutes, the amount of music that could fit on 78 rpm records. The ability to record extended performances by the era’s jazz greats simply didn’t exist.

Or so it was thought.

It turns out that one man—a jazz musician and technical genius—figured out a way. But during his lifetime, William Savory kept these recordings largely to himself. He refused to reveal how many recordings he had and what performances they contained. He let only a very few of his recordings be heard by a small number of acquaintances. Over time, the Savory collection became a tantalizing enigma to jazz connoisseurs who yearned for access to its treasures.

The mystery ended last summer. Six years after Savory passed away, his collection was acquired by the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. And jazz experts were stunned. The extent and quality of the Savory collection was beyond anything they had imagined.

“I figured there was maybe 50 to 100 unreleased recordings,” says Loren Schoenberg, the museum’s executive director. “I expected to see one box. Instead, I saw dozens of boxes. The Savory collection comprised about a thousand discs of the greatest performers of all time. And all of this was unknown music. It was immediately clear this was a treasure trove.”

Click here to read the rest of “Orphaned Treasures” from the May issue of the ABA Journal.