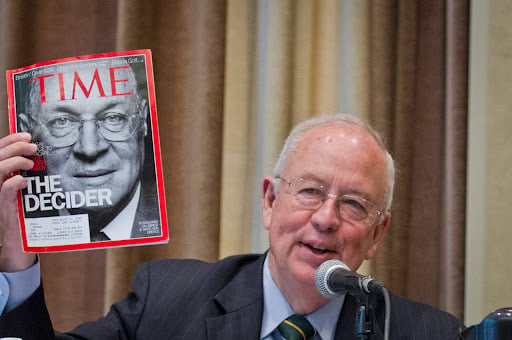

Can the president be indicted? Memo from Ken Starr's office says yes

Ken Starr/Shutterstock.com

A memo prepared for Ken Starr’s office by a prominent law professor argues that a sitting president can be indicted.

The memo by Ronald Rotunda, now a Chapman University law professor, argues “it is proper, constitutional, and legal for a federal grand jury to indict a sitting president for serious criminal acts that are not part of, and are contrary to, the president’s official duties.” The New York Times obtained a copy of the memo (PDF) through the Freedom of Information Act and summarized its contents in a story.

According to the Times, Rotunda’s memo raises the possibility that the special counsel investigating the Trump campaign and its dealings with Russia may have more options than most commentators have assumed.

Starr’s office had prepared a draft indictment for President Bill Clinton, but opted instead to refer Clinton matters to Congress for possible impeachment. The Times is also seeking a copy of the draft indictment.

Nothing in the Constitution or federal law says presidents are immune from prosecution, the Times explains. Some who support the idea that the president is nonetheless immune cite structural principles in the Constitution and the executive branch burdens of a prosecution.

Rotunda emphasized immunity issues in his analysis. He said the speech or debate clause gives limited immunity to senators and representatives for certain actions, and the framers could have specifically given the president immunity if they wanted to do so.

If a president could not be indicted until after he left office, Rotunda said, then the statute of limitations could expire before prosecution.

Rotunda also cited Clinton v. Jones, a 1997 Supreme Court decision that found federal courts were not required to stay Paula Jones’ state civil suit against Clinton for sexual harassment until after his term ended. Rotunda argued that the case led him to believe a criminal indictment would be constitutional “because the public interest in criminal cases is greater.”

Rotunda says in his May 1998 memo that his opinion is based on the power to indict under the independent counsel law, which expired the next year. The independent counsel was supervised by a special three-judge panel that appointed him. The special counsel investigating Russian influence in U.S. elections was appointed by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein under a different law, and that he has supervisory powers.