Criminal injustice: How Netflix's 'The Staircase' illustrates the inequities of our justice system

Michael Peterson and his lawyer, David Rudolf. Photos from Netflix.

I’m fascinated with the fascination over the true-crime genre. It allows audiences to see the unfairness of a system which, too often, keeps its secrets in the shadows.

Many in American society believe our criminal justice system is the best available option in the world. While I agree to a certain degree, the system only works when all parties are aboveboard. If not, it poses just as much opportunity for evil and error as any other system.

In that sense, true-crime often gives the audience a view at true corruption.

Netflix has positioned itself as the true-crime television czar of sorts. Some series in this style are slow-moving with subplots that simmer. Others are relatively fast-paced with episodic endings leaving the audience anxious to turn the next digital page. Some focus more on the technical aspects of the criminal justice system, while others do a better job of intertwining the humanity of those involved.

The Staircase succeeds in this “humanity” department to a degree rarely achieved. The Netflix property delivers an “inside look” at what is happening in the courtroom, but the series also provides a behind-the-scenes view at the people, and preparation, involved in those proceedings. As a result, the reality of the American criminal justice system (which often contains more injustice than justice) hits home hard.

MANY CRIMINAL DEFENDANTS CAN’T AFFORD A DEFENSE

The Staircase focuses on the 2001 death of Kathleen Peterson and the accusation, and subsequent criminal jury trial, of her husband Michael Peterson. When Michael Peterson finds Kathleen dead at the bottom of a staircase in their home, he calls law enforcement, ultimately setting into motion a series of events which consume his life over the next 15 years.

(If you haven’t seen the series yet, reader beware. Here come some spoilers.)

Peterson hires attorney David Rudolf to defend him. The series’ earlier episodes show the economic reality of Peterson’s defense. Consultants, mock juries, experts, and other legal fees soon add up. In one scene, Peterson sits at a table in his home discussing the costs of his criminal representation. The audience learns that the bill is estimated at $750,000.

Peterson questions what “poor people” do when they are caught in the criminal justice system. He brings up a very valid point. Depending on the difficulty of the case, a good defense to murder charges can easily run into the six figures. Plenty of murder cases have been won with much less, but the cost clearly shows that money goes a long way towards justice.

Many people are charged with crimes they cannot afford to defend. Those individuals are left at the mercy of the government. They find themselves caught in the machine. One facet of the government wants to convict them, while the other wants to defend. Sadly, it often seems that the government is much more willing to expend resources on convictions than on acquittals.

QUESTIONABLE CHARACTER EVIDENCE COMES IN TOO OFTEN

As is often the case, surprises are inevitably discovered during trial preparation. The prosecution intends to offer into evidence portions of Peterson’s life in the hopes of damaging his character. Peterson admits that he has lived as a bisexual man, and that he had sexual relations with other men while still married to the deceased.

How does someone’s sexuality make them more or less likely to have killed their spouse? The prosecution introduces that evidence in the jury trial to show Peterson’s marriage to Kathleen was not as perfect as he would have the jury believe. But is Peterson’s sexuality more probative to the allegations of murder or more prejudicial in regards to his character?

The prosecution is also allowed to introduce evidence that, while Peterson was living with his first wife in Germany, one of their family friends was found dead at the bottom of a staircase in 1985. Although the defense objects to the admission of the evidence, the prosecution is still allowed to present it in hopes of convincing the jury the event gave Peterson an idea of how to stage Kathleen’s murder as an accident.

There are various provisions that govern when and why evidence of this type should or should not be allowed in trial. Most often the question comes down to: “Is this evidence more probative or prejudicial?” Far too often evidence is admitted because the idea of prejudice in criminal prosecution is lost on judges.

In my experience, some judges believe the prosecution has a duty to present prejudicial evidence against the defense since our system is adversarial. This position relies on the faulty notion that evidence can only be beneficial or prejudicial. It would follow then that most, if not all, of the evidence the prosecution presents will be prejudicial to some degree against the defendant. After all, the prosecution is trying to convict, so it’s unlikely any of its evidence will be beneficial.

Michael and Kathleen Peterson.

‘EXPERTS’ AREN’T ALWAYS WHAT THEY SEEM

Regardless of the character evidence, the physical evidence seems to be somewhat unfavorable to Peterson. The crime scene photos are a bloody mess. Even as an experienced defense attorney, I kept asking myself how so much blood could result from a fall.

The prosecution seizes on this, and much of their case centers around the testimony of a medical examiner and a bloodstain-analysis expert. The bloodstain-analysis expert becomes, perhaps, the principal witness against Peterson. He testifies to his extensive training and experience. He testifies to his scientific analysis of the blood splatter patterns and his attempts to re-create the same.

The jury ultimately convicts Peterson, and he serves approximately eight years in custody before a new development comes to light. An independent audit of the cases analyzed by the bloodstain analysis expert in Peterson’s trial shows that the “expert” not only lied about his qualifications, but that he had also lied about his experience and credibility.

It’s also discovered the witness’ attempts to re-create the blood splatter had no basis in the relevant scientific community. Furthermore, and most importantly, it is determined that the witness also withheld exculpatory evidence in another trial in which he testified as an expert.

Experts have a great deal of persuasive authority with juries. Most jurisdictions offer a limiting instruction for the jury to consider when weighing out the testimony of an expert, but sometimes the instruction is not sufficient to overcome the inherent bias. The sad reality is that an expert is still just another person. All people, expert or not, have faults, biases, and motives.

IT’S DIFFICULT TO KEEP THE DEFENDANT’S BEST INTERESTS AT HEART

Peterson is granted a new trial as a result of the bloodstain-analysis expert evidence. His previous attorney ultimately gets involved in the case again in the hopes he can get Peterson a plea deal to manslaughter with credit for the time he served as a result of the reversed conviction.

Both Peterson and his attorney know the chances of an acquittal at the new trial are better than they were previously. However, there is no guarantee. The defense attorney discusses how it would be in his own best interest to get a win: it’s almost akin to unfinished business or revenge regarding the previous verdict. Regardless, he also knows that even a “win” at trial won’t fully vindicate the client. The jury returns a verdict of “not guilty” if you are successful. There is no “innocent” verdict.

At the same time, Peterson deals with the decision to go to trial by discussing the pros and cons with his family. His daughters want him to fight. One of them goes so far as to tell Peterson, “I don’t want to just lie down and take this.” It’s easy to see they want vindication, but by personalizing the situation, they almost take the decision out of Peterson’s hands.

Family can often be the voice of reason in a criminal case. At the same time, they can become the driving force behind enabling a defendant’s delusions about the “right” or “correct” decision. Just as attorneys can sway a defendant one way or the other, family members can also cause a case to take an unnecessary or uneducated turn for better or for worse.

PLEA AGREEMENTS AREN’T ALWAYS SATISFACTORY

Peterson eventually realizes that the safe bet is to try and broker a plea agreement. He has already spent eight years of his life in prison. He can’t get that back. The only thing he can hope to accomplish at trial is “winning”—but his son reminds him there is no point in winning a game if the game is not fair to begin with.

He admits the plea deal is what he has been wanting, but he still doesn’t like it. He tells his attorney that the word “guilty” will not come out of his mouth. The family of the deceased wants Peterson to say unequivocally that he is guilty.

Even when the prosecution acquiesces and agrees to an Alford plea (thus allowing Peterson to enter the plea agreement while still maintaining his innocence), the prospect of entering a plea deal still angers him. The emotion is understandable to a point. If a defendant is not guilty, then the mere act of entering the equivalent of a guilty plea, regardless of the reasons behind it, will be painful.

Still, from the perspective of an advocate, it is the best possible outcome—it’s a guarantee, and guarantees are hard to come by in the legal arena. Peterson finally has a chance at closure. He finally has a chance to end the case and put everything behind him. He has the ability to forever end the possibility of serving a life sentence in prison.

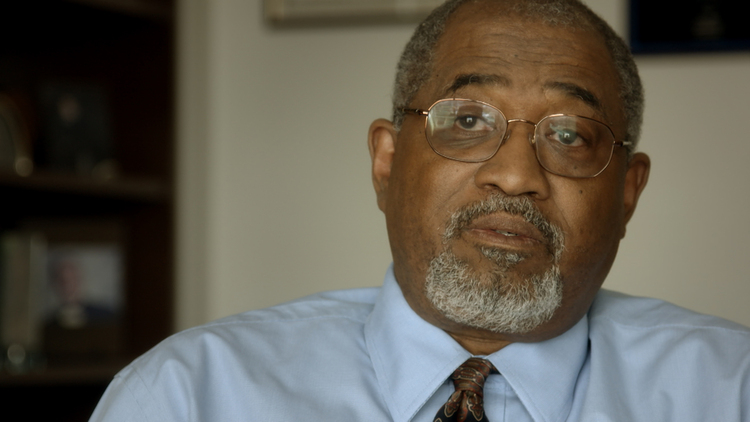

Judge Orlando Hudson.

‘AN INNOCENT MAN DOES NOT PLEAD GUILTY’

Peterson accepts the plea deal, rationalizing that it is in his best interest “because the system is not fair.” During his plea colloquy, Peterson refuses to say anything on his own behalf. Peterson’s attorney explains to the judge the reasoning for his client entering into the plea deal with the prosecution: “He is simply not willing to play again at what he perceives to be an unfair or crooked table.”

The family of Peterson’s deceased wife is not happy with the outcome. Her sisters appear at the plea to give victim’s impact statements. One of the sisters laments that “an innocent man does not plead guilty.” However, that is far from the truth.

Defendants plead guilty to crimes they did not commit every single day all over the United States. That is a byproduct of a system that relies on bartering and agreements to keep the dockets from becoming too clogged. Guilty pleas are the grease necessary for our current criminal justice system to operate as the well-oiled machine many would have you believe.

The judge closes the documentary. He advises that his rulings would likely have been different had the case gone to trial a second time. He would have kept out the evidence of the staircase death from Germany and Peterson’s bisexual lifestyle. His final statement to the documentary team is telling: “I think I could have had a reasonable doubt.”

Adam Banner

Adam R. Banner is the founder and lead attorney at the Oklahoma Legal Group, a criminal defense law firm in Oklahoma City. Mr. Banner’s practice focuses solely on state and federal criminal defense. He represents the accused against allegations of sex crimes, violent crimes, drug crimes, and white collar crimes.

The study of law isn’t for everyone, yet its practice and procedure seems to permeate pop culture at an increasing rate. This column is about the intersection of law and pop culture in an attempt to separate the real from the ridiculous.