History shows how SCOTUS nominations play out in election years

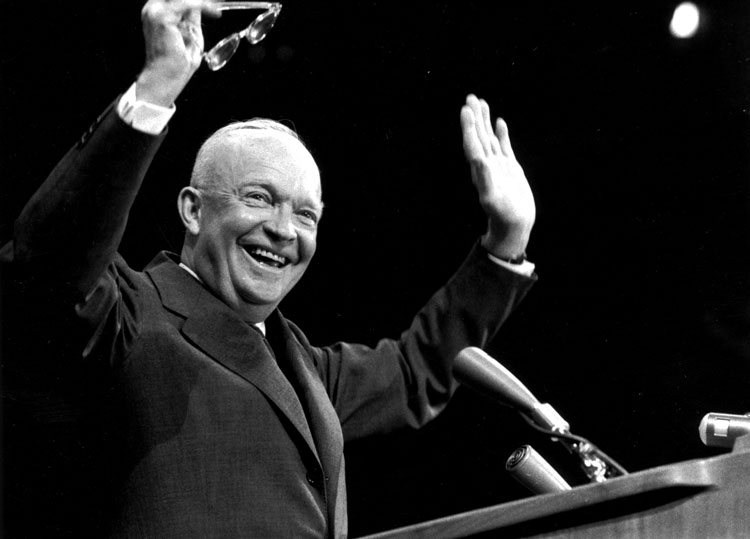

President Dwight D. Eisenhower named William J. Brennan for a U.S. Supreme Court vacancy through a recess appointment shortly before the 1956 presidential election.

A Republican president with two U.S. Supreme Court nominations under his belt was seeking a second term and had uncertain prospects just weeks before the election. A vacancy on the court unexpectedly arose. Suddenly, political calculations were a major factor as the president weighed contenders for the lifetime appointment.

This was 1956, when President Dwight D. Eisenhower was running for re-election against Democrat Adlai Stevenson II. In September of that year, Justice Sherman Minton informed the president of his intention to retire as of Oct. 15 because of health concerns. Eisenhower, seeking to gain support in the Northeast and among Catholic voters, settled on William J. Brennan Jr., a 50-year-old Irish Catholic and lifelong Democrat who served on the New Jersey Supreme Court.

“This was a purely political appointment,” says Ilya Shapiro, the author of a new book, Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of America’s Highest Court. “Ike said, ‘I need to shore up some support.’”

Shapiro, the director of the Robert E. Levy Center for Constitutional Studies at the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington, says that while there are some surface parallels between that episode and the vacancy created by the Sept. 18 death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg just weeks before the presidential election, 1956 “was a very different time from what is happening now.”

On the other hand, he says in an interview, President Donald J. Trump is deciding who to nominate for a close-to-the-election high court vacancy, and “political considerations are coming into play.”

Looking to precedent

Barely 24 hours after Ginsburg died of pancreatic cancer, Trump announced his intention to fill the seat and that the nominee would be a woman. Among the names being circulated are Judge Amy Coney Barrett of the 7th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals in Chicago, who might provide the president a boost among conservatives; and Judge Barbara Lagoa of the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, a Cuban American and former state supreme court justice in Florida, whose nomination could help the president in that state.

Republican leaders in the Senate have indicated they will move to confirm a nominee, perhaps before Election Day on Nov. 3 or in a lame-duck legislative session before a new Congress begins in early January.

Those same leaders have brushed aside charges of hypocrisy over the fact that they refused give a hearing or vote in 2016 on President Barack Obama’s nomination of Judge Merrick B. Garland to fill the seat of Justice Antonin Scalia, who had died in February of that election year.

Advocates on the right say that history supports their view that Trump is entitled to nominate Ginsburg’s replacement, and the Senate may appropriately take up that nomination, whether before Election Day or in a lame-duck session if former Vice President Joseph R. Biden Jr., the Democratic nominee, is elected president (and/or Democrats retake the Senate).

Dan McLaughlin wrote in the National Review that 29 times there has been an open Supreme Court vacancy in a presidential election year, or in a lame-duck session before the next presidential inauguration.

“The president made a nomination in all twenty-nine cases,” he wrote. McLaughlin added that “19 times between 1796 and 1968, presidents have sought to fill a Supreme Court vacancy in a presidential-election year while their party controlled the Senate. Ten of those nominations came before the election; nine of the 10 were successful.”

By contrast, when the president and Senate were from opposite parties, there have been 10 vacancies resulting in a presidential election-year or post-election nomination. In six of the 10 cases, the president made a nomination before Election Day, but only one of those was confirmed by the Senate controlled by the opposite party. That was President Grover Cleveland’s nomination of Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller in 1888.

Advocates on the left, meanwhile, cite President Abraham Lincoln’s decision not to fill the vacancy created by the death of Chief Justice Roger B. Taney in 1864, just 27 days before the election, until after Lincoln won. Salmon P. Chase, the president’s former secretary of the treasury, was nominated Dec. 6, 1964 and confirmed the same day.

“You have the precedent of the only time a justice died this close to an election,” Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Minnesota Democrat who is a member of the Judiciary Committee, said on NBC’s Meet the Press on Sept. 20. “Abraham Lincoln was president, and he made the decision to wait until after the election. And you have the fact that people are voting right now. And I think that creates pressure on my colleagues, honestly. That’s what a democracy is about.”

Long history of nomination fights

Shapiro’s book is a breezy but engaging journey through the history of the Supreme Court nomination process starting at the beginning, with President George Washington stocking the new court with its first six members and then restocking it amid complete turnover and then some during his two terms. The first president made 14 high court nominations, 10 of which were confirmed. One nomination was rejected (John Rutledge for chief justice), one was withdrawn (and resubmitted), and two nominees declined to serve.

“While the confirmation process may not have always been the spectacle it is today, nominations to the highest court were often contentious political struggles,” he writes.

After Washington, such 19th century presidents as James Madison, John Quincy Adams, John Tyler, Millard Fillmore, and James Buchanan all had Supreme Court nominees who were thwarted, the book details. In the 20th century, Warren G. Harding, Herbert Hoover, Eisenhower, Lyndon Baines Johnson, Richard M. Nixon and Ronald Reagan all had failed nominations.

The “battle royale” over Reagan’s failed nomination of Judge Robert H. Bork to replace centrist Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr. stands out for many as the fight that changed everything, Shapiro says. But he argues that recent titanic battles over Bork, Clarence Thomas, Garland, Neil M. Gorsuch and Brett M. Kavanaugh are part of a larger problem that began under President Franklin D. Roosevelt of a shift in power from the legislative branch to the federal courts and to executive agencies.

“The Supreme Court is called upon to decide, often by a one-vote margin, massive social controversies, ranging from abortion and affirmative action to gun rights and same-sex marriage,” Shapiro writes. “The judiciary affects public policy more than it ever did—and those decisions increasingly turn on the party of the president who nominated the judge or justice.”

A recess appointment

Shapiro devotes only a few paragraphs to Eisenhower’s tapping of Brennan for the court vacancy that arose just before the 1956 election. While there are some conspicuous parallels to the current situation, they may be outweighed by the differences.

For one, Sherman Minton was no Ruth Bader Ginsburg. He was a former U.S. senator from Indiana serving as a federal appeals court judge when President Harry S. Truman tapped him for the high court in 1949. He served seven mostly unremarkable years when on Sept. 7, 1956, he sent Eisenhower a resignation letter that cited health problems that made continuing to perform his “exacting duties” too difficult, according to Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion, by Seth Stern and Stephen Wermiel.

Eisenhower decided he wanted a judge with lower court experience in state or federal courts. And urged on by Cardinal Francis Spellman of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, the president wanted a Catholic. Brennan, who had been on the radar of Attorney General Herbert Brownell, fit the bill.

Eisenhower gave Brennan a recess appointment to the court, and Brennan was sworn in on Oct. 16, still weeks before the election. His full-fledged nomination and confirmation hearing would come after the election. Recess appointments to the high court were not unheard of then. Three of Eisenhower’s nominees started with recess appointments—Warren, Brennan and Potter Stewart. Shapiro notes that in 1960, the Senate passed a nonbinding resolution “expressing the sense of the Senate that the president should not make recess appointments to the Supreme Court, except to prevent or end a breakdown in the administration of the court’s business.”

There have been no recess appointments to the high court since then, though the idea was briefly floated when Obama’s nomination of Garland was stalled in 2016.

Boosted by the Brennan appointment and other factors, Eisenhower went on to easily defeat Stevenson in 1956.

Shapiro’s book examines the many ideas floated to reform the process for selecting Supreme Court justices or the court itself. He comes out in favor of term limits. But for now, another vacancy arising in the middle of a presidential election will steal the spotlight.

“We’re in a difficult situation,” Shapiro says.