Learning Experience

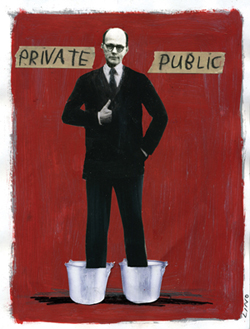

Illustration by Lino

In February, Long Island-based Newsday began publishing a series of articles reporting on the complicated relationship between a lawyer and several school districts he represented.

According to those reports, five different school districts listed Lawrence W. Reich as a full-time employee, often simultaneously, at various times over a period of 28 years. As a result, Reich, a private practitioner since 1978, accrued 42 years in the New York State and Local Employees’ Retirement System and began collecting an annual pension of $61,459 upon his retirement from the system in 2006.

While listing Reich as a full-time employee, the school districts paid him part-time annual salaries, which in 2006 totaled about $97,000, reported Newsday. Meanwhile, Ingerman Smith in Hauppauge, N.Y., where Reich was a partner until his departure in October, collected millions of dollars in fees from the same districts.

Follow-up stories in Newsday reported that 23 of Long Island’s 124 school districts had one or more private attorneys on their payrolls, listed as full- or part-time employees and earning pension and medical benefits.

Investigations were initiated by the FBI, the Internal Revenue Service, the New York state comptroller’s office and New York Attorney General Andrew M. Cuomo.

On April 10, Cuomo announced that his office had issued subpoenas to 90 lawyers and 180 school districts on Long Island and in upstate New York. A few days later, Cuomo said he was expanding his probe to include all forms of local government across the state and other types of professional consultants in addition to lawyers. (New York City was excluded because it has a separate pension and retirement system.)

Meanwhile, New York Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli said the school districts incorrectly classified Reich as an employee. The comptroller also suspended the pensions of Reich and Albert D’Agostino, another Long Island attorney who worked with several school districts.

Reich’s attorney, Peter Tomao of Garden City, N.Y., told the ABA Journal that Reich was unaware until 2005 that the school districts had been reporting him incorrectly as a full-time staff member. Moreover, Tomao says, Reich gained no particular benefit from the designation because state employees can be credited with no more than 260 days per year toward pension benefits, regardless of their classification.

“Not one bit of evidence suggests he was intentionally misleading anyone,” Tomao says.

In a statement posted Feb. 29 on its website, Ingerman Smith said that no other lawyer at the firm had been identified as an employee of a school district the firm represents, and that the firm was cooperating with the investigations. John H. Gross, a partner at Ingerman Smith, told the ABA Journal that the firm carefully avoided double billing by maintaining a sharp separation between Reich’s salaried work and work billed by the firm.

Ingerman Smith’s site said it “severed” its relationship with Reich in October 2007. Reich moved to another Long Island firm, Jaspan Schlesinger Hoffman in Garden City. He left that firm after the Newsday stories broke and is now retired, according to Tomao.

MOTIVATIONS MATTER

The office responsible for attorney discipline matters in Nassau and Suffolk counties on Long Island declined to say whether any lawyers are being investigated for possible violations of the New York Code of Professional Responsibility stemming from their employment arrangements with school districts.

But a legal finding in either a criminal or civil action that a lawyer participated in a fraudulent employment arrangement would likely trigger disciplinary proceedings as well.

It is misconduct for a lawyer to engage in activities prejudicial to the administration of justice or that involve dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation under both the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct (Rule 8.4) and the ABA Model Code of Professional Responsibility (Disciplinary Rule 1-102), which the Model Rules supplanted in 1983. New York is the only state that still follows the Model Code, which, unlike the Model Rules, contains a combination of aspirational standards for lawyers along with specific disciplinary rules.

The Model Code also prohibits lawyers from engaging in “illegal conduct involving moral turpitude.” The Model Rules do not contain that language, but they state that it is misconduct for a lawyer “to commit a criminal act that reflects adversely on the lawyer’s honesty, trustworthiness or fitness as a lawyer in other respects.”

Even if lawyers are not found guilty of wrongdoing in legal proceedings, they still could face disciplinary action under professional conduct rules, which generally apply a “clear and convincing evidence” standard that is somewhat lower than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard that applies in criminal cases, says Diane L. Karpman, a principal at Karpman & Associates in Los Angeles, where she represents lawyers in professional conduct matters.

She is a member of the ABA Standing Committee on Professionalism.

But experts on professional conduct issues caution against a rush to judgment in situations like the investigation in New York. They note there is nothing inherently improper about a private lawyer taking on a salaried job with a government entity while keeping his or her position in a law firm. It all depends on how and why it was done.

“There’s no prohibition against multiple hats,” says Stephen Gillers, a professor at New York University School of Law who chairs the Joint Committee on Lawyer Regulation of the ABA Center for Professional Responsibility. “The real question is whether there’s value received and whether the lawyer is truly doing the work he’s being paid for.”

But the reason for the agreement also must be considered, Gillers says. “Did the school board negotiate a good deal for itself, or was this simply a back door way to give a lawyer a benefit to which he was not entitled as a reward or a private act of generosity?” asks Gillers. “It’s a distinction that makes a difference.”

A separation of duties within a firm to avoid double billing can raise questions if it potentially favors one lawyer at the firm, says Susan Brotman, a lawyer in New York City who is president of the Association of Professional Responsibility Lawyers. In the school district context, for instance, it can appear to be “a ruse through which that person enjoys rights under the New York state retirement system that he or she would not be eligible for as a private contractor,” Brotman says.

A related issue is whether the school districts were authorized to enter into the agreements, Gillers says. Under New York law, for instance, only people who meet the definition of “employees” are entitled to pension benefits. The comptroller said Reich was not an employee because the school districts didn’t directly supervise him, give him a workspace, document his hours worked and set his hours.

At least one school district maintains that it handled the employment arrangements properly. The Hewlett-Woodmere school district on Long Island said in a statement posted on its website that during 2004-06 it had properly employed a part-time private attorney who was given set hours, a desk, a phone, supplies and specified “nonadversarial” duties, and that the arrangement had been cost-saving and advantageous to the district.

SAFETY IN PAPER TRAILS

Another question is whether the arrangements involved misrepresentation or subterfuge—even if it was committed without the immediate knowledge of the lawyers retained.

“A lawyer is not allowed to violate a rule through the actions of another,” says Roy D. Simon Jr., a professor at Hofstra Law School in Hempstead, N.Y. “At the very least, he had a duty to at least inquire as to whether the school district was doing anything improper. He should have asked, ‘By what law or regulation am I being added to the payroll?’ ”

Karpman says it is plausible that many of the lawyers were simply unaware that their status with the school districts may have violated state law. “If you have a lawyer retained to do leases or supplier contracts, and he fills out the paperwork his employer demands, I don’t know if he would have a special duty to investigate the pension and retirement provisions of his employer,” she says. “The lawyer would obviously depend on the client’s assurance that the arrangement was legal.”

But she agrees that lawyers should ask about the legal status of outside employment arrangements, and they should protect themselves by keeping a paper trail of the answers they receive.

Karpman notes that many of the employment agreements with school districts date back to the 1970s, when legal distinctions between employees and independent contractors weren’t as clear as they are now.

Each of the cases in New York involving school districts and outside lawyers on their payrolls will need to be evaluated individually, says Luke Bierman, general counsel to the New York state comptroller. “We expect it will be a very long effort.”

Kristin Choo is a freelance writer in New York City.