10 Questions: Prosecutor uses her experience as a survivor to advocate for domestic violence victims

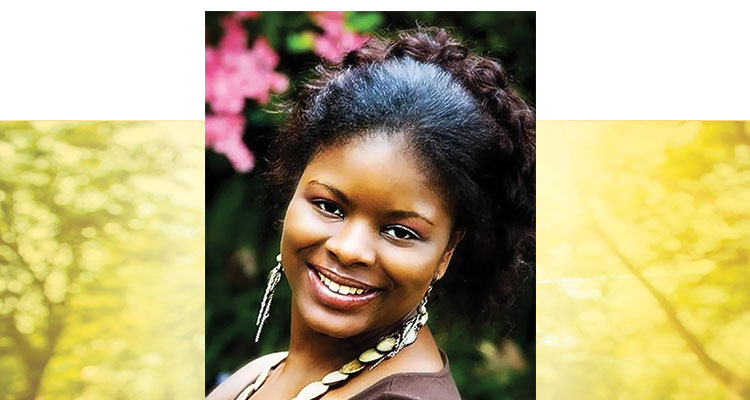

Photo by Lauren Carter.

On April 25, 2014, Atlanta prosecutor April W. Ross was shot three times—in the jaw, back and right arm—by her estranged husband, who later killed himself. Ross survived the attack, but in many respects that was the easy part. It took Ross, now a quadriplegic, a year and a half to regain the strength and stamina necessary to return to work, and return she did. She’s back at her desk at the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office, where she is now assigned to the domestic violence trial unit. It’s no coincidence. Ross now uses her experience to improve the legal process, from setting legislative agendas to helping lawyers improve the efficacy of their communication with victims. She shares her own story to empower survivors to seek justice and stay safe. She also provides peer support counseling to people recovering from spinal cord injuries and is writing a book about her relationship with the man who tried to murder her. Ross hopes to spread awareness about early signs of abusive relationships.

In law school, you had worked with a pro bono program that helped domestic violence victims get protective orders. Did this familiarity with domestic violence issues in any way provide a clue or a warning that this could happen to you?

No, no. I did not see it coming. As a young attorney, I was passionate about domestic violence. I did not want to see people hurt. But at the same time, I did not fully understand what abusive relationships are actually about. I was used to seeing people coming in with horrible stories of physical abuse. I got jaded—I thought, my relationship can’t be abusive because there is no physical abuse. Even though it was an unhealthy relationship, it was not what I had been conditioned to think of as abusive. Now that this happened to me, I understand it in a different context. Of course I wish it hadn’t happened, but I think it’s made me a better lawyer and a better advocate.

As an advocate, you often speak about domestic violence issues with law enforcement, prosecutors and also with victims. What is your message?

One thing I teach a lot is that physical abuse is just one part of identifying an abusive relationship. But the lack of physical violence does not mean you are not in danger.

During your months of grueling rehabilitation, was returning to work a motivator for you? Was it one of your goals?

I think it was an off-and-on goal. Most people who have this kind of injury don’t go back to work, or they don’t go back to what they were doing before they were injured. I was blessed that I had an employer that was willing to do whatever it took for me to come back and was very generous with accommodations. I remember my mentor kept saying, “There’s nothing wrong with your mind, and that’s all we need!”

I imagine you were dealing with a lot of emotional trauma, too, right?

Yes. I was dealing with emotional stress, with PTSD and a lot of other things. After about a year, I was depressed. I had nothing to occupy my time, and I was thinking I wasn’t valuable. That’s when I really started thinking, I don’t want the rest of my life to be defined by being a victim or a survivor or being in a wheelchair. I wanted to get back to work.

Has this experience—everything you lived through—made you more passionate about your work, about your ability to make a difference?

Oh, yeah. My passion has intensified. I have been working towards being a prosecutor since my second year of law school! But now I have to temper my passion with my endurance. Which is frustrating because I want to do more. My motto this year is “slow down.” If I am tired or in pain, I just have to learn to stop. It’s better to head home and lay down and work in bed than to stay at the office pushing through and then being in excruciating pain.

What is your mobility and function like?

My injury was to my cervical spine at C-7. I have very little sensation or movement from the chest down. But both arms are full-function. I can write, drive, get myself in and out of my chair and type at a keyboard, although I do have limited hand dexterity. I cook. I can walk my dogs—well, they walk. I say, “Are you ready to walk and roll?”

What’s your setup like at work? Do you use adaptive technology or a special desk?

I don’t need a lot. I have special dictation software for my computer and a special keyboard and touch-screen monitor. I also have a headphone set so I don’t have to hold the phone. I use both a power and a manual chair at work, so when I am in my manual chair, I use a regular desk, but I also have a table that raises and lowers. I can raise it higher when I am in my power chair and lower it for my manual chair.

Fulton County installed automatic doors in the secure entrance to my office, and they gave me a parking spot at the courthouse where the judges park, which is pretty cool.

Are you still facing any physical challenges?

My stamina is still a challenge. I have a lot of back and shoulder pain, which makes it hard to have long days in the chair. I am a lot slower—I don’t move at the same speed I did before. Sometimes that’s frustrating, especially not having good hand function at work in an environment that’s very paper-intensive. When I am doing a hearing, I have to handle paper and evidence and check notes and go back and forth to the witness stand, and that’s challenging. I had initially thought I could use an iPad instead of the legal pads I used to use, but now I just have someone with me to help me, to hop up and bring something to the witness or find something. It’s a team effort. The judges I am in front of so far have been accommodating and understanding—they certainly have not given me any breaks.

That’s good, right?

Yes, I don’t want to be coddled. That’s more dispiriting than anything.

On the topic of trials, it’s not unreasonable to think that at some point you’ll try a domestic violence case. How do you think your personal experience will be addressed with the jury—or will it?

I am not sure. That’s something I am curious to see. But as far as trials go, I don’t want my chair to be a focus. I don’t want any sympathy from a jury or anything like that. When it comes to victims I talk to, I try to be careful, because every relationship, scenario and person is different. I am careful about using my story when I talk to victims, but I think sometimes they’ll hear me out a little more if they see me in the chair. No one wants to be mean to someone in a chair! But if a woman is reluctant to prosecute, no amount of me telling my story will change that. We can still prosecute our case, we just have to be more creative when we advocate for that person’s safety.

This article was published in the April 2019 ABA Journal magazine with the title "Supporting Survivors: After her estranged husband almost killed her, this Atlanta prosecutor uses her experience to advocate for domestic violence victims."