Eloquent silence teaches lawyers about power of the pause

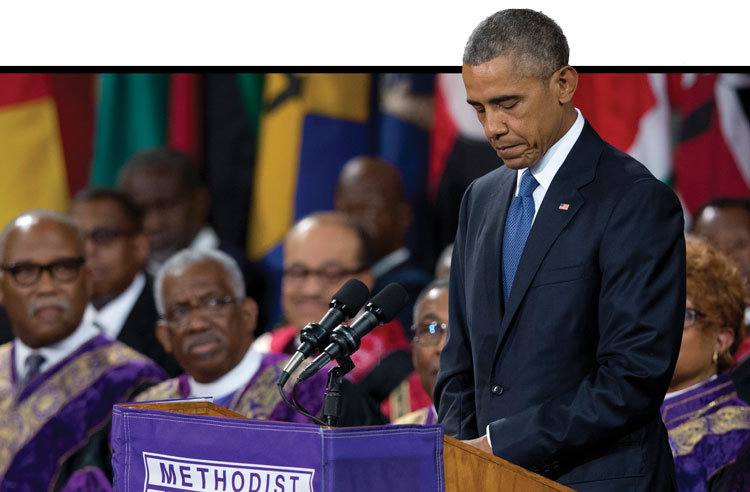

Former President Barack Obama took inspiration from Martin Luther King Jr. and Abraham Lincoln during his 2015 eulogy for nine victims of a church shooting. Photograph by AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster.

In his book Cruel and Unusual: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment, Michael Meltsner writes about a young Anthony Amsterdam. A federal prosecutor in the District of Columbia in the early 1960s, Amsterdam was arguing a Fourth Amendment case before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

The legal issue was whether the police had waited long enough after knocking before entering an apartment to execute a search—specifically whether a delay of about 25 seconds was sufficient time to allow for the occupants to answer the door before breaking it down.

Amsterdam began his argument with the formulaic: “May it please the court ... .” Then he stopped. He remained respectfully silent. According to Meltsner, during the silence, “the few seconds seemed an eternity.” The judges became uncomfortable and were about to break in themselves when Amsterdam finally commenced his argument: “That was the length of time that the police waited before they broke into the defendant’s apartment.” The silence worked, and Amsterdam won the appeal.

More recently, in 2015 President Barack Obama eulogized the Rev. Clementa Pinckney and eight parishioners who were assassinated by Dylann Roof at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Roof later told police he was attempting to foment racial hatred and start a race war.

Obama delivered his speech to a church audience of grieving parishioners and to a vast, live national media audience. The stakes couldn’t have been higher; it was a historic speech at a dangerous cultural moment and attempted to mark the occasion as an inflection point of cultural transformation.

Obama’s speech was a church eulogy ennobling the lives of the fallen. But it was equally a political argument acknowledging our dark legacy of slavery as our country’s original sin, identifying slavery as the reason for the Civil War and recognizing the legacies of slavery and racism that remain in our society to this day. This included the pain inflicted by the continuing celebration of the Confederate flag.

He also addressed society’s need for gun control and the need to address systemic injustice within the criminal justice system based on racial and economic bias.

How did Obama connect all these remarkably diverse subjects? He employed a poetic lyricism that built purposefully toward a crucial, eloquent and reflective silence. For models, Obama drew on the church sermons of Martin Luther King Jr. and the battlefield Civil War speeches of Abraham Lincoln. Like King, Obama broke his speech into stanzalike sections and call-and-response musicality. Like King and Lincoln, Obama used strategic pauses and silence to mark crucial transition points in his performance.

The core theme of Obama’s eulogy was grace—our need to receive grace and honor it in our lives and our actions, as it was received and honored through the lives and the deaths of Pinckney and the parishioners. Obama put it this way: “We don’t earn grace. We’re all sinners. We don’t deserve it. But God gives it to us anyway.” He personally reworked his speechwriters’ initial drafts on his long, yellow legal pads, drawing a recurring inspirational refrain from the lyrics of his favorite hymn, “Amazing Grace.”

Obama’s speech concluded with a dramatic and reflective 13-second silence, transitioning into his heartfelt yet slightly off-key singing of the first stanza of “Amazing Grace.” He then delivered a powerful crescendo—calling out the names of the dead, accompanied by PowerPoint images of the departed.

Silent impact

The precise timing and use of prolonged “live” silences were crucial to the successes of Amsterdam’s and Obama’s presentations and crucial to the impact of the arguments they were making.

For Amsterdam, the silence enabled the judges to grasp viscerally the length of time the police waited uncomfortably on one side of the apartment door while not knowing what might be waiting for them on the other, in a way his words alone could not.

For Obama, the use of pauses and silence was more complex. The pauses provided musical beats in stanzalike sections. In the vocabulary of narrative theory, the shorter silences were like ellipses (spaces in time) building to the final silence that allowed the audience to reflect on his words and sink into shared emotion.

The final silence provided a handoff, or transition forward, to Obama’s rendition of “Amazing Grace,” and then quickly sequenced to calling out the names of the dead, providing an emotional ending on a King-like evocation of religious community and redemption.

Philip N. Meyer, a professor at Vermont Law School, is the author of Storytelling for Lawyers. This article was published in the July 2018 ABA Journal magazine with the title “Sounds of Silence: From a 1960s federal prosecutor to a former president, what lawyers can learn about the power of the pause.”