Jan. 7, 1795: The Yazoo Land Fraud Becomes Law

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

From Georgia’s first settlement in 1733 as the 13th and last of the American colonies, its history was one of persistent contradictions. Conceived in popular history as a refuge for imprisoned debtors, early Georgia was every bit as prudish as older religious outposts to the north. It was first governed by a corporate board from London and—seemingly whimsically—forbade rum, lawyers and Catholics. It also resisted the advent of slavery until 1751, long after the odious practice gained an economic stranglehold on the rest of the American South.

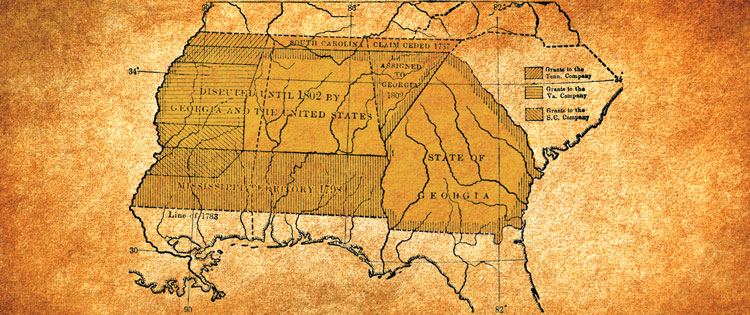

Because the province of Georgia was viewed primarily as a buffer between England’s more established northern colonies and Spain’s holdings in Florida and beyond, its original grant included a massive swath of land that stretched westward above the 31st parallel, all the way, as the grant hyperbolically described it, to “the south seas.” In historical reality, that meant as far west as the Mississippi River.

After the Revolutionary War, America’s vast frontier holdings became a full-blown attraction to pioneers, profiteers, politicians, thieves and opportunists who envisioned fortunes to be made from the newly acquired wilderness. Georgia, like other states rich in real estate and little else, was vulnerable to almost any scheme that seemed likely to attract a new population of white settlers to displace the indigenous people within its borders.

John Randolph. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

By 1794, a consortium of four companies sought to buy 40 million acres of Georgia’s western land for $500,000, or 1.25 cents per acre. Because stockholders in the companies included some of the most influential legislators and officials in state and national government, the sale was authorized by the Georgia legislature without serious opposition. By one account, all but one of the legislators who voted for the sale were stockholders in the companies that benefited from the Yazoo Land Act, signed into law by Gov. George Matthews on Jan. 7, 1795.

The sale yielded an immense and almost instantaneous profit to the four companies: the Georgia Co., the Tennessee Co., the Upper Mississippi Co. and the Georgia-Mississippi Co. It also yielded a fiery popular opposition to what quickly became excoriated as the “Yazoo legislature.” When a newly elected “anti-Yazoo” state legislature convened in early 1796, the Yazoo Land Act was repealed and burned by state officials.

Although the sale had been annulled, the business of recovery proved problematic. In anticipation of the repeal, speculators had sold much of the land to out-of-state interests at remarkable profits. On the day of the repeal, for example, the Georgia-Mississippi Co. sold 11 million acres for eight times the purchase price. Moreover, many landholders who had been unaware of the controversy simply refused to yield back their ownership. For much of the next decade, state officials moved unsuccessfully to undo the damage wrought by a massive legislative fraud.

In a fragile new nation that still struggled with the tensions between state sovereignty and federal power, the issues of compensation and land repatriation became a volatile national concern. By 1804, the Yazoo controversy had swept into the U.S. Congress, where Virginia planter John Randolph raged against fellow Virginian James Madison and any attempts to settle Yazoo claims, even in the national interest. Their feud resulted in a stalemate in Congress, leaving the issue to be decided by the U.S. Supreme Court.

In Fletcher v. Peck (1810), land speculators Robert Fletcher and John Peck argued about the validity of a sale of Yazoo land that took place between them. The question was whether Georgia’s 1796 repeal of the Yazoo Land Act could invalidate their contract.

In a decision that helped establish primacy and durability of the private contract, Chief Justice John Marshall ruled that the Yazoo Land Act, even if it proved to be a fraud on the public, made the ensuing contracts legal.