Today at SCOTUS: Mohammed Atta & His Harmonica Quartet

Mike Sacks is guest-blogging at ABAJournal.com during his unique U.S. Supreme Court project, First One @ One First, which is to be first in line for politically salient arguments at the high court this term. Mike is a third-year law student at Georgetown University interested in legal journalism and the intersection of law and politics.

Early in this morning’s oral argument (PDF) in Holder v. Humanitarian Law Project, Justice Anthony Kennedy plainly remarked, “this is a difficult case for me.” The issue was whether a 1996 federal law banning “material support” to designated terrorist organizations infringed on the First Amendment rights of a group seeking to train Turkey’s Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and Sri Lanka’s now-defeated Tamil Tigers in international law advocacy and peacemaking.

But Kennedy’s pondering of the disputed law’s ephemeral distinction between proscribable conduct and protected speech appeared to come to an abrupt halt when Solicitor General Elena Kagan conceded to Justice Kennedy that the law could ban lawyers from submitting amicus briefs on behalf of designated terrorist organizations. Here was the government telling attorneys who they could and could not represent in a court of law—not a winning argument before a tribunal of, well, attorneys.

The court’s liberal bloc—Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Sonia Sotomayor—had already displayed their skepticism towards the government’s asserted ability to criminalize speech meant to assist a terrorist organization’s legal activities. Sotomayor even suggested that “under the definition of this statute, teaching these members to play the harmonica would be unlawful.”

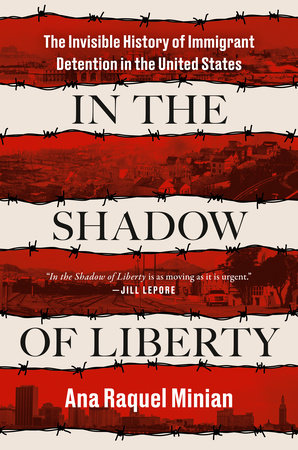

Line outside the Supreme Court on Tuesday.

Photo by Mike Sacks

In response, Kagan quipped, “I think the first thing I would say is there are not a whole lot of people going around trying to teach al-Qaida how to play harmonicas.” Justice Antonin Scalia, the lone vocal supporter of the government’s argument, saved the court further talk of harmonicas by shoving Sotomayor’s hypothetical into an absurd vision of chief 9/11 hijacker “Mohammed Atta and his harmonica quartet” touring the country to “make a lot of money.”

Meanwhile, Justice Clarence Thomas just this week marked his streak of silence’s fourth anniversary, but one could assume he’d ally with Scalia in this case, given his previous willingness to prohibit intensely disfavored expressive activity by casting it as pure conduct.

If Kagan’s amicus-ban assertion seemed to crystallize for Kennedy the infirmity of the law in question, Justice Alito may have fallen off the government’s wagon when Kagan explained that Congress did not intend to criminalize one’s meeting with or joining a designated terrorist organization. Queried Alito:

Could you explain how someone could be a member of one of these organizations without providing a service to the organization? Simply by lending one’s name as a member; that might be regarded as a service. If you attended a meeting and you helped to arrange the chairs in advance or clean up afterwards, you would be providing a service to the organization.

However, Alito may have asked this question simply to get Kagan to walk back her distinction between simple membership and criminal service-providing so that he could more easily side with the government. After all, he was the sole supporter of the government’s position in United States v. Stevens, in which the court is likely to rule a federal ban on depictions of animal cruelty to be an unconstitutionally overbroad restriction on speech. But walk it back Kagan did not.

Even if Alito still finds a way to join Scalia, even if the loquacious Kennedy forgets that lawyers may be silenced, and even if silent Thomas sides at conference with Sotomayor, Chief Justice Roberts signaled an openness to killing the law as applied to HLP. That is, as long as the court got no government blood on its hands.

During HLP counsel David D. Cole’s rebuttal, Roberts asked, “why don’t we remand it to the lower courts to apply strict scrutiny if we agree with you that” the law does, in fact, prohibit pure speech as opposed to conduct that incidentally touches speech?

Cole quickly endorsed this plan, knowing that strict scrutiny is nearly always “strict in theory, but fatal in fact.”

But just as soon as Chief Justice Roberts offered up a pleasing resolution for this “difficult” case, Justice Sotomayor jumped in to close the morning with the argument that if money is speech—as the court strongly affirmed in Citizens United—then Congress could have been onto something after all when it found that money is so fungible that “if you give [terrorist groups] money for legitimate means … it’s going to be siphoned off and used for illegitimate means.” Such a justification for a ban on money-as-speech, Sotomayor suggested, could be “enough under strict scrutiny or under a lesser standard, reasonable fit standard.”

Perhaps Sotomayor believed this, perhaps she was trying to impress upon her conservative colleagues the duty they owed to HLP if they were to remain fully faithful to the First Amendment principles they forcefully articulated in Citizens United.

Either way, Sotomayor’s mixed signals forced the court to submit HLP the same way it entered: a difficult case, indeed.

Contact Mike Sacks at .(JavaScript must be enabled to view this email address).

Last updated at 2:54 p.m. to fully identify David Cole.