Inside the mind of Faulkner estate's lawsuit-filing watchdog

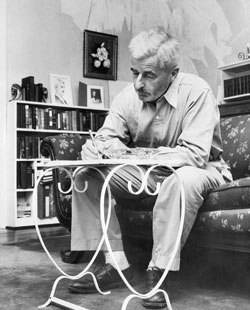

William Faulkner ©Bettmann/Corbis/AP Images

Last October, the owners of the rights to the literary works of the late William Faulkner sued Sony Pictures Classics in a Mississippi federal court because a line from Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun was (mis)quoted in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. The copyright and trademark claims are being spearheaded by Lee Caplin, a Hollywood producer (Ali) and University of Virginia Law School graduate who manages Faulkner’s literary estate. Caplin is a longtime Faulkner devotee (they were once neighbors) who also has a connection with Allen, whom he calls one of his favorite filmmakers: The two once shared the same lawyer.

In the entertainment universe, as anyone who has played Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon knows, there’s not much separation from one luminary to the next—even from an author who died 50 years ago to an artist living today. In fact, that was one of the themes of Midnight in Paris, which follows a screenwriter’s imaginary journey to the 1920s, where he encounters, among others, Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. In the lawsuit, the Faulkner estate challenges whether the connections are drawn too close: Does the film misappropriate Faulkner’s words (“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”) or confuse audiences about the source of origin?

Caplin defends against arguments that the movie’s Faulkner lift was fair use by saying that such protection against a copyright claim isn’t afforded to a commercial endeavor. (Midnight in Paris grossed $151 million at the box office.) Faulkner’s estate also sued defense contractor Northrop Grumman and the Washington Post over an Independence Day ad that lifted a quote from a 1956 Faulkner essay. The suit settled.

So what would be fair use? “Barack Obama recently made a speech that quoted Faulkner,” he says. “That didn’t make any money.”

But what if, after leaving office, Obama published a moneymaking book that printed his speeches, Faulkner quote included? Caplin thinks a moment. “Interesting question, maybe,” he says.

And in his day, could Faulkner quote Herman Melville without getting into legal trouble from the Melville estate? “That depends on whether he was quoting Melville as a comment on Melville’s work,” says Caplin. “That’s why fair use is so nerve-wracking.”

And what if Midnight in Paris didn’t include any Faulkner quotations but rather presented him as a character like the film did with Hemingway? Caplin answers: “If I was representing the Hemingway estate, and they portrayed him as something he was not—unseemly and mocking—I would think that would be a problem.”

For the record, Caplin says he thought the Hemingway character was great.