Letters: Blocking Access

BLOCKING ACCESS

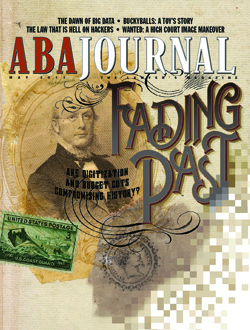

Regarding “Fading Past: Are digitization and budget cuts compromising history?” May: A couple of other access-to-justice considerations are important as well.

PDF documents are not generally accessible to screen-reading software unless properly tagged and formatted. As libraries, courts and governmental entities switch to digital formats, they need to be sure those formats are accessible to people with disabilities. Other critical groups, like the self-represented and seniors, will have more difficulty getting information if it is only available online. Incarcerated individuals, in particular, have little or no access to technology. The more resources are moved online, the more difficult it is for those individuals to participate effectively in the justice system.

Pamela Cardullo Ortiz

Annapolis, Md.

Why is there not a law stating that this is the way to keep needed information and every state would have to conform? I know: politics. But surely having easier access would be cost-effective for lawyers in the long run.

Library computers could be made available at courthouses for the general public to use with time limits on daily use. Most of the material would be confusing for use in the general public anyway. I drove 70 miles for research in a university’s law library only to find that it was digitized. What law was on paper was in small, half-sheet-paper size and just stuck together on a shelf with no order at all. What books were available were fast being phased out or stored somewhere else—but not for public use.

Pamela Brown

Boaz, Ala.

I was looking to read a law online to know my options in a situation, but I found it very hard to get to the text of the law, even though I’m a computer person. It can be impossible for somebody less techie.

I figured the first step to solving this problem would be to convert the texts of laws into one format. XML standard was the obvious choice and I started doing it in February 2011 with a project called Law Delta. I also figured the next several steps but couldn’t keep working on the project alone and pro bono for long. Nevertheless, Law Delta was nominated for an Innovating Justice Award.

It’s unbelievable how different the structure and presentation of laws is from state to state. A unified framework will not infringe on the ability of local legislatures to create local laws, but is required for a modern country as it promotes trust and understanding for its citizens.

Daniel Malikov

Toronto

LAWYERLY ADVICE

Regarding “Legal Aid,” May: After I got a bachelor’s in business administration, I completed my first year of law school. At the end of that year I was very discouraged about my results. I enrolled in a program that would lead to a PhD in educational administration.

It was my uncle, then the registrar of the University of North Dakota, who convinced me to continue in law since the degree would open doors. He pointed to the chancellor of the university, who was not an educator but held degrees in business and law.

I still believe that combination provides the greatest flexibility in career choices. I did not enter the private practice of law until I was in my early 50s and have not experienced the burnout I have frequently seen in attorneys who went directly from law school to private practice.

George J. Claseman

Las Vegas

ENCRYPTION TIPS

Regarding “Reality Bytes,” April, about new ABA rules requiring lawyers to keep up with technology relevant to the client and the representation: The State Bar of Texas Computer & Technology Section (which I chair) has launched an initiative to explore the issues around data privacy and encryption. We’ve developed a one-hour presentation that includes a guide to creating and using encryption containers with free encryption software (the presentation is approved in Texas for one hour of ethics credit). Our article on the subject was featured in the Texas Bar Journal’s February issue.

Jason Smith

Houston

EXPANDING THE DISCUSSION OVER GIDEON

The profession is rightly focusing this year on the failure of the justice system to meet the promise of Gideon v. Wainwright in the 50 years since the decision was handed down (“Living Up to the Gideon Ideal,” March); adequate funding is a constitutional imperative.

There is, however, an urgent need to expand the discussion to include a civil right to counsel in basic human needs cases. Finding money for the unpopular and voiceless is no easy task, whether in criminal or civil proceedings. But it stands to reason that those whose basic human needs (such as housing, health and safety) are protected in civil proceedings are less likely to eventually utilize public dollars through homeless shelters, public health care facilities, and even criminal proceedings and prisons that further tax the indigent defense system.

Fundamental fairness also demands this broader conversation. Gideon is based on the constitutional right to a fair trial before one can be deprived of liberty, and our belief that the assistance of counsel is essential to obtaining a fair trial. Although no such right has been found with respect to most civil proceedings, few would disagree that—especially when faced with a landlord or insurance company represented by counsel—the ability of a layperson to effectively present a claim or defense without counsel is no better than that of an unrepresented defendant facing prison when prosecuted by a district attorney. In either situation, lawyers are essential to ensuring a fair trial.

Finally, the denial of justice undermines public confidence in our courtrooms, whether civil or criminal. Facing 30 days in prison without a lawyer is a frightening prospect for those who cannot afford representation; facing homelessness from a wrongful eviction, or a serious illness for which health insurance benefits are wrongly denied, is no less frightening or consequential.

Robert L. Rothman

Atlanta