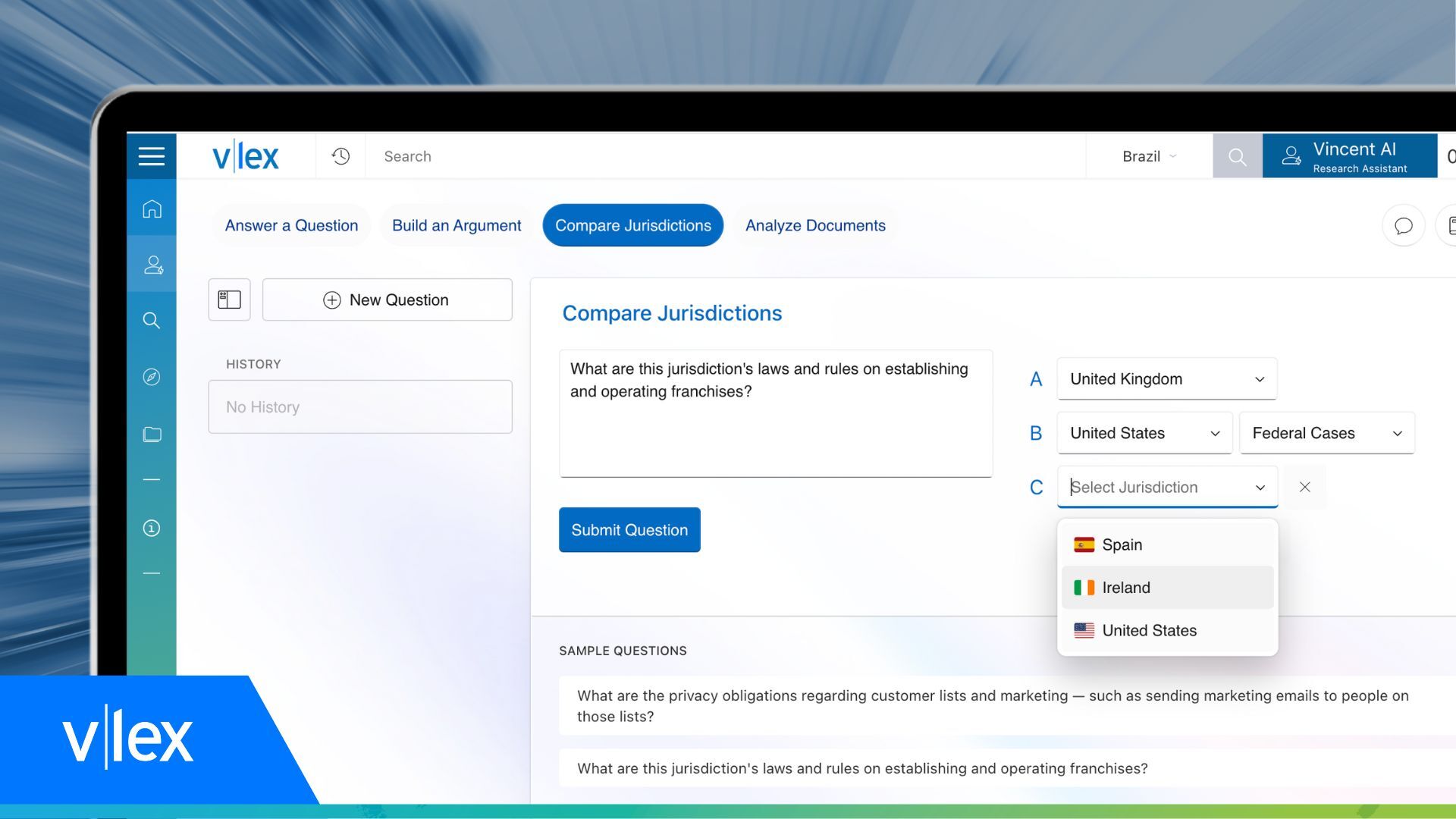

Catch and Kill: Can tabloids hide behind the First Amendment?

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/Shutterstock

One Sunday morning in February of last year, Paul S. Ryan, an attorney at Common Cause, a grassroots organization that works to uphold democratic principles, got up early, as he regularly does, and read through the latest news. When he came to a story in the New York Times he had been following, he drank some coffee, ate breakfast with his wife and young son, and went to work.

Ryan, who is Common Cause’s vice president of policy and litigation, does not regularly work on weekends. But the Times story had new details in an evolving scandal in which the company that owns the National Enquirer had paid $150,000 to former Playboy model Karen McDougal to buy the rights to a story about her affair with Donald Trump before he became president. The company, American Media Inc., never had any intention of running the story. Instead, at the direction of David Pecker, AMI’s chairman, president and CEO—and a longtime friend of Trump’s—the company wanted to make sure no one else could run the story. Buying a story specifically to suppress it is known in the tabloid world as “catch and kill.”

Ryan had been keeping up with news about the deal, which took place in August 2016 and was first revealed by the Wall Street Journal in the days before the presidential election. In particular, he wondered if the payment might eventually be traced back to the Trump campaign. That Sunday, Feb. 18, 2018, journalists at the New York Times did exactly that, reporting in a story headlined “Tools of Trump’s Fixer: Payouts, Intimidation and the Tabloids,” that Trump’s lawyer—Michael Cohen—had been involved in the National Enquirer’s transaction with McDougal. If that were true, Ryan thought the payment likely violated the Federal Election Campaign Act, which prohibits corporate contributions to candidates for federal office, including “in-kind” contributions made on behalf of, or “in consultation, cooperation, or concert with” someone. The act also requires that any contributions be reported to the Federal Election Commission.

“Voters have a right to know who is spending money to influence their vote on Election Day,” Ryan says. “Here we had a $150,000 payment to influence voters by keeping away from voters information voters would undoubtedly find interesting within two months of a presidential general election in coordination with a presidential candidate.”

Ryan stayed at his Washington, D.C., office for several hours that Sunday drafting complaints against AMI, Trump and the Trump campaign for the Department of Justice and the FEC. He continued to work on the complaints the next day, even though his offices—and the federal government’s—were closed for Presidents Day.

That Monday, he ran the drafts by his boss, Common Cause President Karen Hobert Flynn, and a colleague who had previously worked at the FEC. Then, as is required for any litigation initiated by Common Cause, he sought approval from the litigation committee of the organization’s national board. He sent an email requesting approval at 11:57 a.m. At 11:59 a.m., he got his first yes. Four others came in by 1:36 p.m. The last committee member asked a few clarifying questions, and after receiving Ryan’s answers gave the greenlight at 4:14 p.m.

“The only time we do a phone call is if there’s some disagreement,” Ryan explains. “But here, there was none. I just got a bunch of quick approval emails.”

The next day, Feb. 20, Common Cause filed the complaints. The organization has several other cases on its docket, but the AMI/McDougal cases have captivated the nation’s attention, not only because of the parties involved—a president and a Playboy playmate—but because of the historic clash between two of the most basic principles of democracy: a free press and fair elections.

Tale as old as time

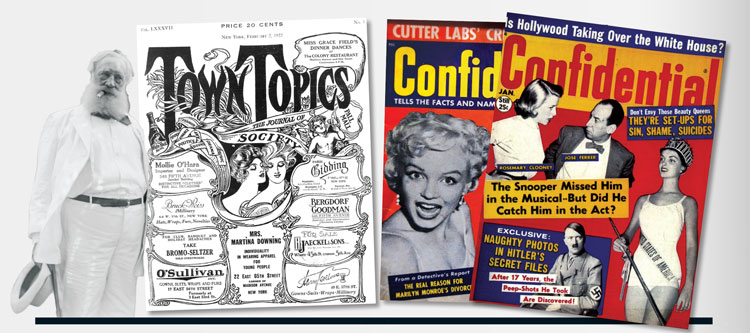

Shady journalism is probably as old as the profession. Like any other job performed by humans, it is vulnerable to corruption. Reports of publishers squelching stories for reasons that have nothing to do with the news are easy to find. In the early 1900s, Col. William d’Alton Mann, a Civil War hero, was known for blackmailing wealthy individuals who did not want him to print embarrassing stories about them in his weekly magazine, Town Topics. In the 1950s, Confidential magazine killed salacious stories about certain celebrities in exchange for sensational stories about other celebrities, according to a law review article by University of Buffalo School of Law professor Samantha Barbas. Upon the request of one major studio, for instance, the publication agreed not to print articles about Rock Hudson’s sexuality, running instead the jail record of actor Rory Calhoun. Around the same time, Drew Pearson, a well-known Washington, D.C., columnist, apparently held back stories on the promise of political support for policies or people he believed in.

Earlier evidence of withholding stories for personal or political gain can be attributed to Col. William d’Alton Mann’s “Town Topics”, from the 1900s to the ‘20s, and to “Confidential” magazine in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Photos by Bain News Service, publisher/loc.gov; Peter Horree/The Advertising Archives/Alamy Stock Photo

It’s harder to know how long catch and kill—the tactic at the heart of the Common Cause complaints—has been around. By its very definition, the public isn’t supposed to hear about such deals or the stories they seek to squash. Some historians who study journalism say they hadn’t heard of the term—or much about the practice—before the AMI/McDougal case came to light.

“If you did a search of books published about the press in the late 20th century, boy, I don’t think you’re going to see that phrase,” says Tom Leonard, a professor emeritus at the University of California at Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism, who has written about the development of American media. “It was a new phrase to me.”

Some experts have suggested the practice—at least in the United States—is limited to tabloids such as the National Enquirer, particularly under Pecker’s direction.

And, in fact, deals that sound very similar to McDougal’s took place at the magazine with Pecker at the helm when Arnold Schwarzenegger was running for governor of California in 2003.

In August of that year, as Schwarzenegger was negotiating a consulting deal with AMI, the company paid $20,000 to a woman in exchange for her confidentiality about an alleged affair she had with the candidate over a number of years. Later, AMI reportedly paid $1,000 to silence a friend of the woman’s who also knew about the affair and $2,000 for a Playboy video reportedly depicting Schwarzenegger grabbing a scantily clad woman. According to Los Angeles Times stories about the deals, the company never sought additional information about the affair—even though it had published a cover piece about the relationship two years earlier—and didn’t mention the video, either. One Los Angeles Times article about the deals described them as the “David Pecker Project.”

Author Laurence Leamer, who wrote a book about Schwarzenegger and a column for the Los Angeles Times describing the AMI deal on his behalf, characterized the payoffs as the start of catch-and-kill arrangements of this kind.

Arnold Schwarzenegger hits the campaign trail in 2003. Photos by Newsmakers; Vukasin Boskovic; Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images

“That’s where it all began,” he says of the Schwarzenegger example. “Certainly, people kill stories and are paid off to kill stories, but this specific practice, that pattern began with Pecker. Before Pecker took over, the National Enquirer had a kind of rude integrity. I don’t think they would have done that in the earlier era.”

Stu Zakim, who was senior vice president of corporate communications at AMI from 2004 to 2006, agrees that the practice of buying stories to suppress them was “David Pecker-specific.”

“It was really about collecting favors,” he says. As in, “we won’t do this story in exchange for you helping us” in some other way.

In the McDougal deal—and in other actions, including regularly using the National Enquirer to attack Hillary Clinton in the lead-up to the 2016 election—what Pecker was really buying, Zakim says, was future “access to the White House.” According to a New York Times report, Pecker may have cashed in on his favor in the summer of 2017 when he visited Trump at the White House with someone who in turn had access to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, where Pecker apparently hoped to do business. AMI followed up with a nearly 100-page glossy magazine about Saudi Arabia in the spring of 2018.

“What media owner wouldn’t give their eyetooth to have that kind of access to the president?” Zakim asks.

An attorney for AMI referred inquiries about the McDougal deal to a company spokesperson, who did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Cohen pleaded guilty in August to campaign finance law violations stemming from the transaction, and in December, he was sentenced to three years in prison for those and other crimes. (Cohen’s original plea agreement refers to the National Enquirer, Trump, McDougal and Pecker as “Magazine-1,” “Individual-1,” “Woman-1” and “Chairman-1,” respectively.) Although AMI previously claimed in a lawsuit by McDougal that it had merely exercised its “editorial discretion not to publish” her story, the company later admitted in a non-prosecution agreement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York that it had made the deal “in concert with a candidate’s presidential campaign … to suppress the woman’s story so as to prevent it from influencing the election.”

First Amendment scholars and veteran journalists agree catch and kill is unethical and scoff at the notion that it might be considered journalism. The National Enquirer regularly pays for stories, a practice that makes many mainstream journalists squeamish. For example, the magazine broke several stories about O.J. Simpson and reported on an affair Democratic presidential candidate John Edwards had well before any mainstream media did, in part by paying for scoops. But with the McDougal catch-and-kill agreement, the publication paid not to run a story.

“If that’s not the opposite of journalism, it’s certainly very close,” says Theodore J. Boutrous Jr., a partner at Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher who represented McDougal in the early stages of her lawsuit against AMI. The case settled in April 2018.

Gene Policinski, the CEO of the Freedom Forum Institute and the First Amendment Center, agrees.

“The free press is not for journalists to know something and not tell the public,” he says. “The whole point—the reason the founders protected this right so strongly—is that they saw the benefit of the press acting as a surrogate for everyone else.”

Still, it’s not at all clear that catch and kill is necessarily illegal. What matters is the context: If a magazine pays a source to suppress a negative story about a celebrity, that’s sleazy; if someone at the magazine later uses that story to extort the celebrity, that’s probably illegal.

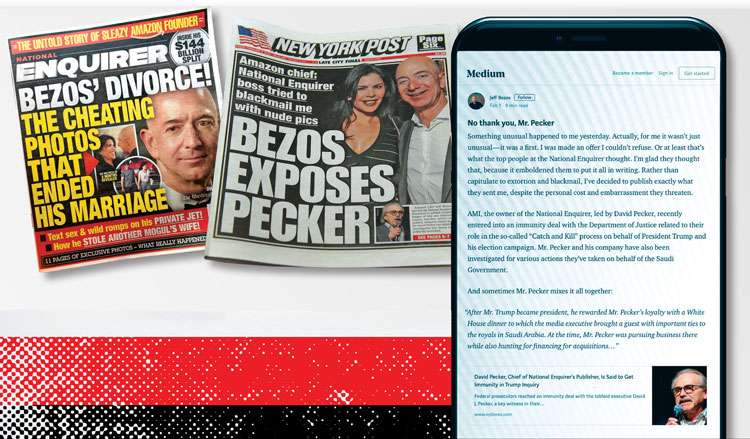

Which could be the case in Pecker’s latest contretemps: the alleged extortion of Jeff Bezos, Amazon founder and owner of the Washington Post. The world’s richest man claims Pecker threatened to publish graphic selfies unless Bezos agreed to publicly state that the Enquirer had no political motivation for running a multipage exposé of Bezos’ extramarital affair. Bezos alleges Pecker used catch-and-kill tactics against him out of political animus related to Pecker’s friendship with the president. Since running for office, Trump has routinely bashed Bezos and the Post for what he considers negative coverage.

While the Bezos case could affect Pecker’s plea deal with prosecutors, if investigators determine extortion, the McDougal case implicates a host of other legal considerations—campaign finance laws in particular.

The target of a “National Enquirer” expose, Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos told his side of the story on the blogger site, “Medium”, which was reported by the “New York Post”. Photos by Brenan Sharp/ABA Journal; Stephanie Keith/Getty Images; Wayne Slezak photography/Shutterstock

“This was all about keeping McDougal quiet in the context of the election,” says Common Cause’s Ryan. “That’s what made this an obvious campaign finance law violation to me.”

One possible defense to any charge of campaign finance violations in the AMI/McDougal deal would come from the Federal Election Campaign Act’s distinction between campaign expenses and “personal use” expenses. (Edwards went with the personal use defense when he was unsuccessfully prosecuted for alleged in-kind contributions made to the woman with whom he had an affair.) Cohen and AMI both have admitted the McDougal payment’s “principal purpose” was to prevent McDougal’s story from influencing the election.

FECA also includes a built-in carve-out for the media so that the press can report on political stories or candidates and publish opinion pieces or editorials without fear of running afoul of prosecutors. The law exempts “any cost incurred in covering or carrying a news story, commentary, or editorial” unless the entity in question is owned by a political party, committee or candidate.

Ryan attempts to pre-empt AMI’s potential use of this exemption in his complaints to the DOJ and FEC, writing that “there is reason to believe” that the media company’s payment to McDougal “was not for the distribution of any ‘news story, commentary, or editorial,’ was not for any ‘legitimate press function,’ and therefore was not covered by the so-called ‘press exemption’ to the definition of ‘expenditure.’ ”

“Particularly on these facts, the catch-and-kill payment was not a payment by a media company to cover or distribute a news story,” he says. “It was a payment for the opposite purpose: to kill a news story.”

There won’t be definitive answers on these questions anytime soon, although some were addressed during a panel discussion in February about catch and kill at the ABA’s Forum on Communications Law. AMI raised the press exemption defense in its response to McDougal’s lawsuit, in the form of an anti-SLAPP, or Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation, motion claiming a First Amendment right not to publish articles.

But a settlement in that case and the company’s non-prosecution agreement in Cohen’s criminal case mean the defense won’t be tested in court.

Experts are divided on whether the government could have successfully proven a campaign finance violation against a media company or its publisher on the AMI/McDougal facts. They are also divided on whether the government should have even tried. Would such a prosecution have been merely a one-off effort to hold one specific man (Pecker) accountable for his actions to benefit another specific man (Trump) during a political campaign? Or would it be a step down a road that eventually leads to a whittling away of the First Amendment?

Boutrous, a prominent media attorney and constitutional law expert, says he is “sympathetic” to concerns about “chipping away at the First Amendment.” But he says he believes the AMI case could have been prosecuted and that any precedent it set would be confined to its unique circumstances. “This is so extraordinary—it’s so contrary to fundamental First Amendment values. It’s so different than anything news organizations do—that pursuing civil or criminal claims in this context, particularly under these specific facts, does not threaten to blow up or even undermine in the least the First Amendment,” he says.

Richard L. Hasen, a professor at the University of California, Irvine School of Law and an expert in campaign finance regulation, agrees, saying such a prosecution would not be “going down the slippery slope” toward narrowing press freedoms.

“I haven’t spoken to any journalist who actually engages in catch and kill, and it doesn’t sound like the sort of thing journalists would want to do,” he says. “Journalists are not typically going to be thinking: ‘I really want to pay money to get some stories that I’ll never publish.’ I don’t think those who protect the freedom of the press are going to cry if the National Enquirer is found liable for not publishing a story.”

But others are not so sure. Bradley A. Smith, a former FEC chairman and founder of the Institute for Free Speech, says the AMI/McDougal case would be “the easy case if you want to penetrate the press exemption.” He cautions against doing so because of the possibility that other, harder cases might then be pursued.

“If you’re going to have a press exemption to these laws, you kind of have to have a press exemption,” says Smith, now a professor at Capital University Law School. “The press exemption is lost if every time the press does something, you can file a complaint and do an investigation into their motives. That’s why I would be very loath to move on this.”

Kathleen Culver, director of the Center for Journalism Ethics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, says codifying journalism ethics in case law would be dangerous for the profession. “We should be very concerned about the power that cedes to the government,” she says. “A lot of people would like to see the government sanction the press, but that flies in the face of free expression guarantees.”

Culver says our constitutional system of a free press may “allow for bad actors,” but it also allows for editorial decisions like the ones made by the New York Times and Washington Post to publish stories about the Pentagon Papers. In that case, she says, “critical information was revealed because of that freedom.”

Policinski says the court of public opinion and the profession itself are better suited to deal with ethical lapses like catch and kill, and Culver agrees.

“Part of the reason we know about this practice is because other reporters broke the story,” she says. “It’s journalism itself that’s highlighting this problem.”