Famous forensic scientist says he had 'no motive nor reason' to fabricate evidence

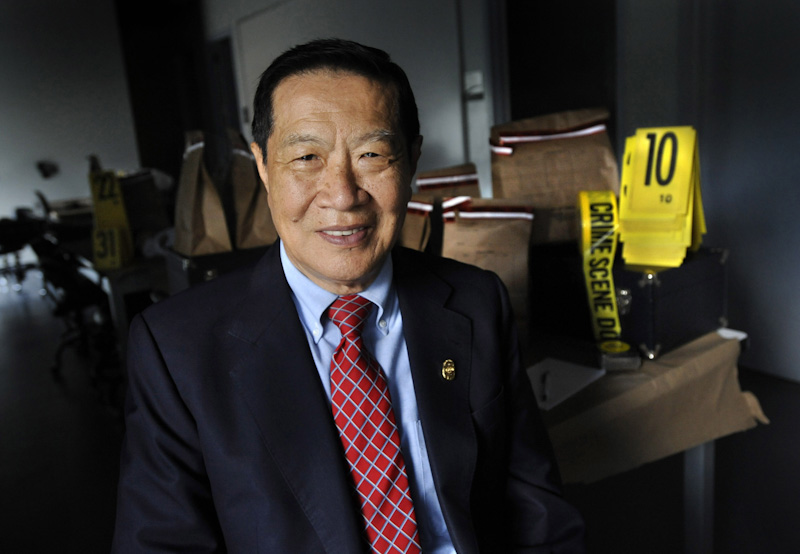

Henry Lee in August 2011 at the Henry C. Lee Institute of Forensic Science on the campus of the University of New Haven in Connecticut. Lee said in a statement regarding a wrongful conviction lawsuit by two men who spent 30 years in prison before their exoneration: “I have no motive nor reason to fabricate evidence.” Photo by Jessica Hill/The Associated Press.

A forensic scientist who became famous after his testimony in the O.J. Simpson murder trial is defending his earlier work after a federal judge found him liable in a wrongful conviction lawsuit by two men who spent 30 years in prison before their exoneration.

U.S. District Judge Victor Bolden of the District of Connecticut granted summary judgment to the plaintiffs, Ralph Birch and Shawn Henning, on their claims that Henry Lee fabricated evidence in their murder cases. Lee headed the Connecticut Forensic Laboratory at the time in question.

Lee later testified in the O.J. Simpson trial and was a consultant in the murder trial of record producer Phil Spector and in the death of 6-year-old JonBenet Ramsey in Colorado.

Bolden ruled in a July 21 opinion.

The Associated Press, the News Times, the Hartford Courant and the Connecticut Mirror reported on Lee’s statement following the decision.

Lee had testified that he tested a red-stained towel at the crime scene in December 1985 and determined that the stain was blood. The towel was then used to support prosecutors’ argument that Birch and Henning didn’t have blood on themselves because they cleaned up after the murder of Everett Carr, who was stabbed 27 times. Nor was there blood found in their car, which did not appear to have been cleaned—it was covered in dirt and filled with sand, sneakers, toiletries, food, blankets, pillows and clothing.

“I have no motive nor reason to fabricate evidence,” Lee said in his statement. “My chemical testing of the towel played no direct role in implicating Mr. Birch and Mr. Henning or anyone else as suspects in this crime. Further, my scientific testimony at their trial included exculpatory evidence, such as a negative finding of blood on their clothing that served to exonerate them.”

Lee didn’t create documents memorializing the blood test, and his experts acknowledged that there was no written documentation or photographic evidence that he performed the test. An evidence tag said police collected a towel with a “blood-like smear.” A now-retired detective later testified that he thought that the towel had not been tested for blood, and that is why he indicated a “blood-like smear.”

The state later conceded that the towel was never tested for blood, according to June 2019 Connecticut Supreme Court decisions that said Birch and Henning were deprived of their due process right to a fair trial. Later DNA tests excluded Henning and Birch as the source of DNA recovered from the crime scene, the Connecticut Supreme Court said in decisions here and here.

Police had focused on Birch and Henning because they had admitted conducting daytime burglaries in the area of the crime. No forensic evidence connected them to the crime. Police suspected that Carr had been killed because he interrupted a burglary, according to the state supreme court.

Prosecutors obtained testimony from Henning’s grandmother and friend, who said Henning called them from jail and said he had been involved in a burglary in which a man was killed, but he was not the killer. The grandmother also said she was told that a dog had been killed, but that did not happen. Prosecutors also obtained testimony from two jailhouse informants who said Birch had confessed to them; they were rewarded for their testimony.

Bolden, an appointee of former President Barack Obama, did not allow Lee to amend his answer to assert a claim of absolute testimonial immunity because he didn’t invoke it until nearly two years after the initial suit was filed. In any event, Bolden said, immunity doesn’t apply because the plaintiffs can establish their claim of fabricated evidence independently of Lee’s testimony.

Lee said in his statement he testified truthfully, and his work on the case was done before Birch and Henning were suspects. He tested the towel and some blood splatters in the sink of an upstairs bathroom using tetramethylbenzidine, a chemical test for blood in the 1980s. There was a positive reaction for the towel and the spots in the sink, he said.

At Lee’s direction, a detective collected the towel and the sink trap and placed them in separate evidence bags. The bags were sealed with evidence tape and placed in the evidence room. Lee later told the prosecutor about the positive result, according to Bolden’s opinion.

“I was not responsible for the documentation, collection of evidence and for photographing the scene,” Lee’s statement said. “For unknown reasons, the towel was never submitted to the lab for a confirmatory blood test at that time.”

Lee said a negative finding for blood when the towel was tested 20 years later shouldn’t be interpreted to mean that there was never a positive test for blood.

“This towel was stored at an evidence room for 20 years,” he said. “It is not unusual for biodegradation, decomposition or denaturation to occur. … In addition, the small amount of blood-like smear evidence may even be consumed during testing or have fallen off the surface of the towel.”

The case continues against other defendants.

Democrat Connecticut Attorney General William Tong plans to appeal, according to news coverage. Lee will be indemnified for damages because he was a state employee, Tong’s office said.