3 lessons in lawyering from the theater

Mohit Gourisaria.

As a practicing attorney and a former actor, I have often asked myself the question Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. asked those in a crowded room at Harvard in 1886: "How can the laborious study of a dry and technical system, the greedy watch for clients and practice of shopkeepers’ arts, the mannerless conflicts over often sordid interests, make out a life?"

It took me several years and an especially rewarding stint as a federal prosecutor before I felt comfortable inviting myself more fully into the workplace. The legal profession, particularly its upper echelons, is not known to encourage authenticity—not the type that runs counter to the stock image of a middle-aged white man in a tailored suit brooding over a sheaf of important-looking papers.

My earliest memory of authentic lawyering is from the first deposition I took without a partner beside me. Freed from the pressure to please (this particular partner liked to yell and thump the table), I decided to show up as myself. I went early, shared a few jokes with the reporter and made the space my own with some deep breaths.

When the witness arrived, I offered him a large square of my chocolate. By the time his company’s lawyers showed up, smirking at the junior associate pitted against them, I knew more about the witness than they did.

Once the deposition began, I pulled my chair closer to him and, as one does with a trusted equal, questioned him from morning till dusk, walking away with no less generous a share of admissions.

But that rare glimpse of belonging left me despairing: In the daily rigors of my work, in the rigid hierarchy that was the law firm ladder, how could I bridge the gap between the person I knew myself to be and the character I felt the pressure to become to find professional success?

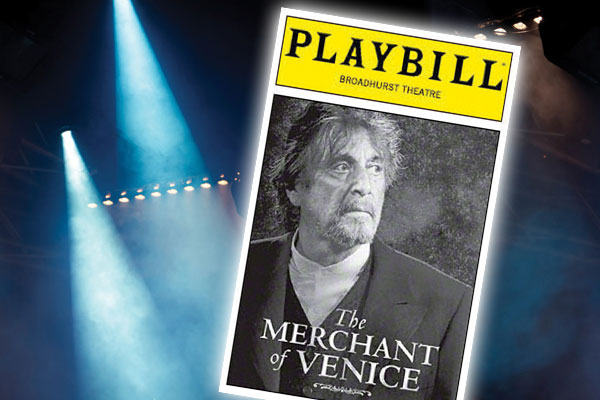

In theater, we are taught never to shy from our multidimensional selves, to force neither uniformity in oneself nor conformity with another. The legal profession has much in common with the theater: complex and fickle; discriminatory and equitable; awe-inspiring and jaded—all at once. Each characteristic is a construct of the social mind and only limited by one’s imagination. Yet as lawyers, we often bring to the workplace only a contained, unidimensional version of ourselves.

Stagecraft—something I teach to law students, though I myself remain a pupil of the practice—is one tool among many to bridge the gap between the profession and the human. It can encourage self-reflection, help build comfort in bringing one’s authentic, complete self to that estuary where livelihood meets personhood.

There are (at least) three lessons from the theater that lawyers, particularly those of us in this competitive, consuming and conforming environment common to white-shoe firms, can borrow.

1. Active listening

I clerked for a brilliant appellate judge who, during oral arguments, would sometimes reframe a party’s position in more persuasive terms than the party’s own lawyer. One might expect that lucky lawyer, his client’s chances greatly improved, to allow the judge to finish speaking, take a pause and say, “That’s exactly right, your honor. And why my client should prevail.” Yet that entire year, I saw lawyer after lawyer, including renowned advocates who charge over $1,500 an hour, interrupt the judge: “Yes, but as I was saying …” and repeat stale arguments to no effect.

Listening is a vulnerable act. It requires ceding control, offering space, breaking the inner monologue. Whatever the cause—insecurity, conceit, bias—my experience is that many of us in the law have difficulty actually listening to others.

Thankfully, listening is a muscle with memory that, like balancing a bicycle or strumming a guitar, may be improved, even perfected, with patient discipline. No matter the context—courtroom, boardroom or the office game room—active listening will make for better and more satisfying lawyering.

2. Who am I?

Even before we become lawyers, we are shaped by the expectations, opportunities and setbacks that mold any human life. A primary question that Konstantin Stanislavski, the Russian theater master whose teachings precursed modern-day “method acting,” asked his actors to consider with regard to their characters: “Who am I?”

When you present, whether in court, over lunch with a client or brainstorming with your colleagues, how do you think you are perceived by others? If someone had to pick one of the following as your predominant adjective, which do you think it would be: powerful, emotional, charismatic, warm or confident?

Each of those comes with a unique strength. The jury will trust the genuinely warm prosecutor before it does the one cloaked in power. And yet someone truly at home in her power or her emotion will be no less effective.

This question also serves to remind us that we can inhabit more than one authentic self, that different occasions call for different versions of us. When interacting with a child victim who has been assaulted, the most commanding and confident will want to borrow from their warm and empathetic selves. But when a corporate client asks a dry procedural question during a board meeting, the most emotional and passionate will want to project confidence and knowledge.

An attorney who wields power before a self-important judge does the client a disservice; to do so over a paralegal who cannot respond in kind does the profession a disservice.

Ultimately, the question of who you want to show up as has no right or even desirable answer; it exists simply to be asked. In inviting self-awareness, lawyers can bring a versatility to the profession that not only lends a sense of belonging but also results in more effective lawyering.

3. Storytelling

Lawyers are fortunate because unlike Scheherazade of The Arabian Nights, only our livelihood, not our life, hangs on this skill. But many of us struggle to tell a story well, and law schools fail to teach law students how to tell a story effectively.

A story has a point, often with a beginning, middle and end; it has a tempo; and it treats its audience as an intelligent, equal partner. Intentional pauses—akin to a beat in acting—can flavor a story more than its words. A good story reflects a perfect conspiracy between body and mind.

As with active listening and self-reflection, storytelling is an art that can be refined and sharpened with practice. If actors must rehearse to play their parts well, so should we, lawyers.

Holmes understood the importance of bridging that gap between the person and the profession, and he knew it to be possible: “I say—and I say no longer with any doubt—that a man may live greatly in the law as well as elsewhere; that there as well as elsewhere his thought may find its unity in an infinite perspective; that there as well as elsewhere he may wreak himself upon life, may drink the bitter cup of heroism, may wear his heart out after the unattainable.”

Mohit Gourisaria is product counsel at Cash App and a lecturer at the University of California at Berkeley School of Law. Previously, he spent a decade as a trial lawyer, including as a federal criminal prosecutor in San Francisco, and clerked on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 2nd Circuit. He studied theater arts in college and performed professionally in Boston before attending law school at Columbia University.

ABAJournal.com is accepting queries for original, thoughtful, nonpromotional articles and commentary by unpaid contributors to run in the Your Voice section. Details and submission guidelines are posted at “Your Submissions, Your Voice.”

This column reflects the opinions of the author and not necessarily the views of the ABA Journal—or the American Bar Association.

Our 12 Greatest Legal Plays

Your Voice submissions

The ABA Journal wants to host and facilitate conversations among lawyers about their profession. We are now accepting thoughtful, non-promotional articles and commentary by unpaid contributors.