Feb. 29, 1984: Guilty plea in Three Mile Island disaster

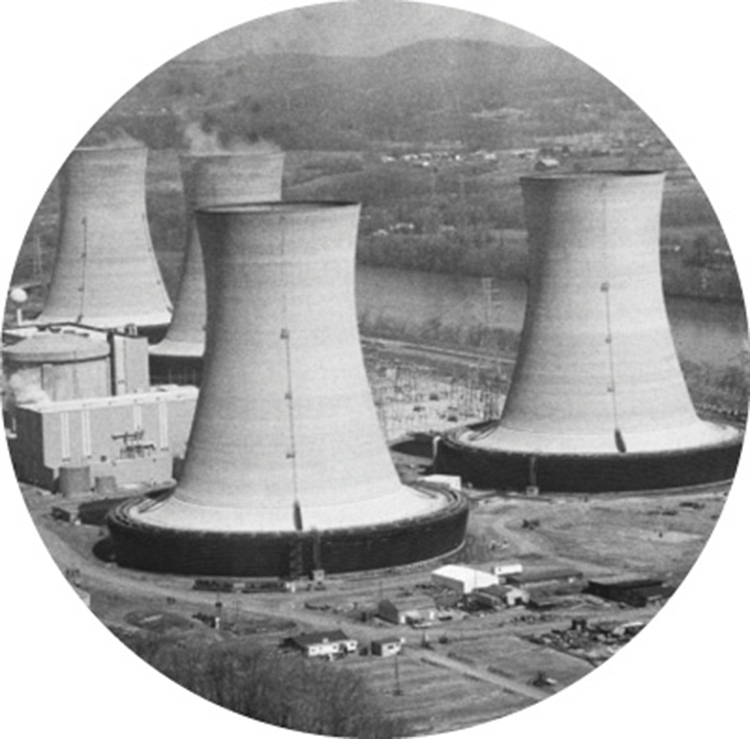

Three Mile Island photo by Bettmann/Contributor via Getty Images

It was 4 a.m. Wednesday, March 28, 1979, when something began to go wrong at Three Mile Island, a nuclear power plant sitting in the middle of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. Whether from electrical or mechanical failure, water in the Unit 2 reactor suddenly stopped flowing from the main feedwater pumps to the steam generators that helped pull heat from the reactor’s radioactive core. The plant’s turbine generator and then the reactor itself shut down, building pressure in the plant’s piping that an attendant relieved by opening a valve.

What followed, according to later investigations, was a chain of human miscues and mechanical failures that resulted—seven years before Chernobyl—in the most destructive and controversial event in the U.S. involving commercial nuclear power.

With the relief valve open, pressure in the reactor ebbed to a safe level, at which point the valve should have closed. It didn’t, although the controls indicated it had. As a result, water coolant continued to drain to a point where the radioactive core became uncovered and began to overheat. Coolant pumps began to vibrate and were shut down. Water began to flood the pressurizer, and its flow was cut back. And with even less water to cool the system, the fissionable material in the core of the reactor began to melt. Within hours, the Unit 2 reactor was lost.

Though the plant was forced to release radioactive steam, the plant’s owner, Metropolitan Edison, assured Pennsylvania authorities that the meltdown presented no health or safety risks. Still, within days, more than 140,000 residents in Central Pennsylvania evacuated.

There were multiple investigations and thousands of lawsuits filed by businesses, residents and government agencies concerned about economic losses, health risks and cleanup costs. At one point, Met Ed filed its own lawsuit against the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, alleging that regulatory delays had contributed to the accident.

Beyond obvious health and security concerns, the incident was a major embarrassment to proponents of commercial nuclear power. Promoted as an environmentally sound alternative to carbon-based fuels, nuclear plants were gaining traction during the rise of OPEC-driven disruptions in the flow and pricing of oil.

But the industry also had been disrupted by rising costs and rising public skepticism, and Three Mile Island was no exception. The Unit 1 reactor had taken six years and $400 million to complete and commission, but Unit 2 took nine years and $700 million. Unit 2 had operated for only three months when the accident occurred.

In meetings with investigators after the accident, one of the control operators, Harold Hartman, alleged problems with the faulty valve had been obvious and probably well known to plant operators. Hartman said he had reported the problem to supervisors, who in turn told him to fudge his reports “to get a good leak rate.” To do so, Hartman testified, the valve was tested constantly—“day and night”—with only the occasionally acceptable readings reported to regulators.

In their own report, NRC investigators also ignored Hartman’s allegations —even though a lead engineer assigned to the group complained Hartman’s sworn assessment about problems with the valve were both believable and “an important factor which affected the course of the accident.”

In November 1983, a federal grand jury in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, indicted Metropolitan Edison for violating its license to operate, violating NRC regulations and one count of making false statements in connection with the leak tests.

On Feb. 29, 1984, the company pleaded guilty to the single count regarding testing and nolo contendere on the other counts. It paid $45,000 in penalties and dedicated a $1 million fund to aid emergency preparedness in towns near the plant.

Although class litigation continued, no medical damages were ever directly attributed to the accident.

In 1996, with the blessing of appeals courts, a trial judge dismissed more than 2,000 lawsuits involving Three Mile Island.

The cleanup for Unit 2 took 14 years and cost an estimated $1 billion to complete. Unit 1, shuttered for the course of the investigations, was allowed to resume operations in 1985. It was decommissioned for economic reasons in September 2019. n