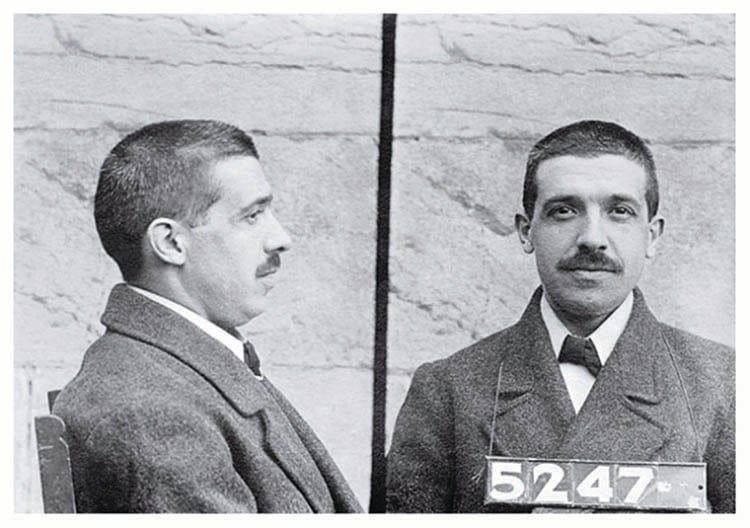

Nov. 30, 1920: Charlie Ponzi pleads guilty to larceny

Photo of Charlie Ponzi by Getty Images/Bettmann/Contributor

By the time he reached his third stretch in prison, Carlo “Charlie” Ponzi was an American celebrity. In a single remarkable year, 1920, the smooth-talking Italian immigrant made money as fast as anyone, ever. In a matter of months, he took in more than $15 million ($200 million today); but by year’s end he had also been arrested, indicted and convicted for a scheme that came to bear his name.

The actual business behind his fraud was both imaginative and legal: a form of arbitrage involving international postal coupons. But in Ponzi’s hands, almost any form of business or employment had a way of straying beyond legal boundaries.

In 1903, as the 21-year-old prodigal son of a once-wealthy family in Lugo, Ponzi landed in Boston with $2.50, a snappy suit and a belief that brains and ambition unencumbered by ethics was key to the American dream.

“Then, as now, nobody gave a rap for ethics,” Ponzi later recalled. “The almighty dollar was the only goal. And its possession placed a person beyond criticism for any breach of ethics incidental to the acquisition of it.”

Ponzi spoke no English when he arrived in the U.S., but the natural polyglot rectified this through entry-level jobs that became part-resumé, part-rap sheet. Moving across New England—often working just long enough to get fired—he landed in Montreal as a clerk in a failing private bank. There, he was convicted of forgery. On his return to the U.S. from the notorious Saint-Vincent-de-Paul Penitentiary, he was caught smuggling Italian immigrants, earning another three-year stretch in Atlanta.

Photo of Charlie Ponzi by Getty Images/Donaldson Collection/Contributor

After a stop in Alabama, he went on to New Orleans and Texas before returning to Boston in 1917. There, he met and married the daughter of fellow Italian immigrants and for a while worked in their family grocery business. But by 1919, bored and broke, Ponzi decided to become a full-time entrepreneur.

He rented an office at 27 School St., intending to solicit foreign investors for an international trade journal. But an international return coupon attached to a letter from Spain inspired his foray into postage stamp arbitrage. He organized the Securities Exchange Co., naming as partners an acquaintance presumed dead and an unsuspecting uncle. All Ponzi needed was money.

Unable to secure a business loan, he created a series of notes that guaranteed a 50% return within 90 days on any investment. And when Ponzi redeemed the first notes in 45 days instead of the full 90, investors began to find him. Although few understood Ponzi’s complex business plan, the high rate of return was an easy sell. By mid-July, investors stood in line outside his office as Ponzi collected as much as $250,000 a day.

The problem was that there was no real business taking place. Ponzi was using cash from new investors to pay off the exorbitant notes. After a series of scathing articles started appearing in a Boston newspaper in July 1920, Ponzi’s fragile pyramid crumbled. He had been under investigation by police and postal inspectors as early as February.

On Sept. 11, Ponzi was indicted by Suffolk County on 22 counts of larceny. And on Oct. 1, a federal grand jury followed with two indictments, each containing 43 counts of mail fraud.

Ponzi approached his options from behind bars with yet another creative scheme. On Nov. 30, he pleaded guilty to a single federal charge—for which he was sentenced to five years in prison—apparently believing that by doing so he could avoid facing the Suffolk County charges. But in April 1921, the superior court issued a writ of habeas corpus requesting the return of Ponzi from federal custody to stand trial. Although federal authorities did not object, Ponzi claimed it was illegal.

In March 1922, in Ponzi v. Fessenden, a unanimous U.S. Supreme Court disagreed. Chief Justice William Howard Taft noted: “The penitentiary is not a place of sanctuary, and an incarcerated convict ought not to enjoy an immunity from trial merely because he is undergoing punishment on some earlier judgment of guilt.”

This story was originally published in the October/November 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Charlie Ponzi Pleads Guilty.”