A tale of two silver markets—and two disasters

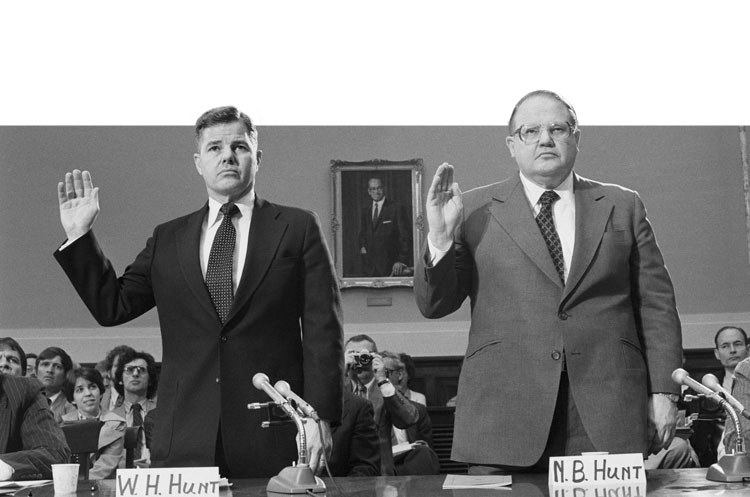

Billionaire Hunt brothers William Herbert (left) and Nelson Bunker are sworn in before a House subcommittee investigating the 1980 collapse of the silver market. Photo by Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images

In the late 1970s, two forces drove anxiety over the nation’s economy: oil and inflation. A 1973 oil embargo prompted by war in the Middle East, followed by a 1979 spike in oil prices, plunged the nation into a dizzying round of inflation peaking at 14 percent, and the U.S. dollar was having trouble remaining stable.

Until 1971, when Richard Nixon freed the U.S. from the gold standard, public faith in currency depended on the price of gold. To average Americans, the tethering of currency to a precious metal, whether gold or silver, seemed a sensible thing. But at least two events in history, both involving silver, revealed the disruptive vulnerabilities of both.

The Panic of 1893 at the New York Stock Exchange. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

On Feb. 20, 1893, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad declared bankruptcy, sparking the Panic of 1893. Though commodity speculation and outsize railroad debts metastasized the panic, many blamed the rivalry between gold and silver for the nation’s economic woes.

Historically, a gold-based currency was considered conservative and stable. But in the decades after the Civil War, farmers in the nation’s rapidly expanding agricultural base grew to resent the increasing strength of the gold-based dollar, which required them, in effect, to pay debts in dollars more valuable than the money they borrowed.

Their need became a movement that championed a silver-based currency and drove passage of the 1890 Sherman Silver Purchase Act. The act required the government to buy 4.5 million ounces of silver each month and issue certificates redeemable for either silver or gold. Though a boon to farmers and miners, it was a spectacular boondoggle. Speculators redeemed silver certificates for gold, then traded it on the open market, depressing the prices of both metals. Speculation was so rampant that by August 1893, President Grover Cleveland called a special session of Congress to repeal the Silver Purchase Act.

Silver remained part of the nation’s coinage and a major tenet of the populism characterized by presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan at the turn of the century. But in 1979, silver speculation returned with a vengeance in the form of billionaires Nelson Bunker and William Herbert Hunt, sons of legendary oilman H.L. Hunt.

Shutterstock

Starting in 1973, the Hunts used their inherited billions to accumulate substantial amounts of silver and soybean futures contracts. But unlike other traders who simply traded contracts for a profit or loss, the Hunts began taking delivery of the actual soybeans and silver, and regulators suspected a goal of market manipulation. By April 1977, the Hunts controlled an estimated third of the U.S. soybean crop. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission stepped in, fining the family $500,000 and asking a federal court to order them to disgorge a three-month profit of up to $100 million.

But barely two years later, the Hunts began the same behavior in the silver market. Again, they not only bought futures contracts but took delivery of the actual silver, accumulating vast stocks of the metal in Swiss vaults. Between January and December 1979, as the price of silver rose from $6 to $32 per ounce, the Hunts borrowed against the increased value of their hoard and used the money to buy more silver—whether in futures contracts, bullion or stock in mining operations. As prices rose, silver poured in from everywhere: jewelry boxes and pawn shops, tea sets and coin collections, bank vaults and burglaries. By the time the price reached $49.45 per ounce on Jan. 18, 1980, the Hunts controlled, in one way or another, more than 69 percent of the world’s silver supply.

On Jan. 21, 1980, at the urging of regulators, the Commodity Exchange, the main marketplace for silver, enacted rules on silver purchases that in effect required the Hunts to sell. As they sold, silver prices declined; the Hunts had to pay their margin calls, and decline begat decline.

The results were disastrous. On March 27, 1980, a day known as “Silver Thursday,” the price of silver plummeted to $10.80 per ounce, and the Hunts, once legendary billionaires, were well on their way to bankruptcy.

Clarification

Print and initial online versions of “A Tale of Two Silver Markets—and Two Disasters” included a mention of Lamar Hunt.

Although Lamar Hunt was involved in substantial silver market investments with his brothers, he was not among Hunt family members involved in the soybean investments penalized by regulators.

The implication was unintentional.