Building the Road Less Traveled

<a href=”http://www.abajournal.com/afghanistan” title=”

Click image to access Sterling DeRamus'

e-mail dispatches from Afghanistan.

When Alabama attorney and Navy Reserve officer Sterling DeRamus got married, his wife felt reasonably sure he would be a full-time solo practitioner and weekend soldier.

After all, the Berlin Wall had fallen and the Soviet Union had shattered into several small nations. It was years before al-Qaida flew planes into the World Trade Center Towers and the Pentagon.

“The Cold War had ended and there did not look like any chance that I’d ever be called up from the Navy Reserves again,” DeRamus says.

But last autumn, nearly six years after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, DeRamus got the call. He had expected to be deployed, so he decided to search out an opportunity he thought would be an adventure: a stint in Afghanistan. He said goodbye to his wife and two small children and left behind the warm, humid, gently rolling hills of Birmingham, bound for Afghanistan’s frozen, rugged, landmine-riddled mountain peaks.

There, DeRamus once again is reporting for duty, this time to a four-star general who oversees his coordination of 26 Provisional Reconstruction Teams, composed of soldiers from 14 nations. Their mission is to help Afghans build in areas so dangerous that even international development agencies fear to tread.

DeRamus, however, relishes the responsibility and the adventure, risking his life to bring the war-ravaged region wells, dams, clinics, schools, electricity and—especially—roads.

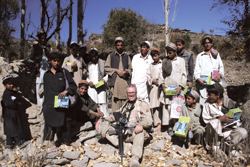

Sterling DeRamus en route to visit U.S. PRTs south

of Kabul. All photos courtesy of Sterling DeRamus.

“Where the road ends, the Taliban begins,” says DeRamus. “Villages always want roads.”

With about $30,000 to $50,000, a PRT can build a micro-hydro power plant that electrifies several villages. But a road must exist or the equipment can’t get there.

That’s where DeRamus and the PRTs come in, however slowly.

Kidnappers, bombs, debris and ambushes are so common, it can take a full day to travel 50 miles. When there are no paths to a town, DeRamus must fly.

Airport is too grand a name for where he lands. In the town of Qal-i-Now, Afghans camp on the airstrip, kids use it as a playground, and the pilot has to buzz it before landing to shoo away a herd of goats. Soviet tanks rusting beside the strip are grim relics of past invasions.

It is a different universe, to say the least, from his normal work environment. But even deep in the Bible Belt, DeRamus was a bit of a risk-taker; he co-authored a book, How to File for Divorce in Alabama, and penned an essay arguing against legislation allowing public schools to teach creationism as science.

MILITARY IN HIS BLOOD

Because he grew up with a career Army father, DeRamus knew, as a reservist, that he would one day be called to duty. He had talked with colleagues who already did tours of duty in Afghanistan, and he was intrigued to hear that many Western-educated Afghan professionals were returning to the country, hoping to create a democracy one day. So he asked his Navy boss to alert him to opportunities to go there.

A view of the hills near the Italian PRT at Herat.

When his boss told DeRamus the PRT chief job might be a good fit, DeRamus had 70 days to prepare his practice and clients for his 9-month absence.

“Most of my larger cases involved co-counsel and I called them,” DeRamus says. “I decided not to inform opposing counsel.

“I feared that until I had my complete turnover in place, they might try to take advantage of the situation to force cheap settlements on my clients.”

There were three lawyers whom DeRamus had worked with and trusted to take over his smaller cases. To bring them up to speed, he made synopses of all those smaller cases: facts, legal theories and status. And right before he left Alabama, they entered an appearance for the court records. DeRamus filed his timesheets with the court so his fees could be calculated correctly. Within two weeks, he was in training, learning to shoot the civilian equivalent of an M-16.

In the role of PRT chief, DeRamus has chances to meet Afghan professionals. “I have colleagues with master’s degrees from all over the U.S.,” he says. “One is a University of North Carolina graduate and since my brother went to Duke, I tease him a lot.”

DeRamus visits a village in the wilderness of Khost,

Qalandar district, where supplies were distributed.

DeRamus says he visited a Provincial Justice Center where he met a judge who says he had been a Soviet prisoner for 11 years during the 1980s. But DeRamus remains somewhat puzzled by the role of attorneys in Afghanistan—both how many actually practice and how they are trained.

There’s a good reason for that, says John Sifton, director of the Brooklyn, N.Y.-based investigative firm One World Research. Sifton also is an attorney who was the Afghanistan researcher for Human Rights Watch.

“No one really knows because the system is very unstructured—loosey-goosey, even,” Sifton explains.

For instance, although Afghanistan has a code of criminal procedure, he says, roads are often frequented by thieves and bandits, making it too perilous to journey to file formal complaints in an urban criminal court. There is legal education to be had, but the path is flexible, at best.

“Kabul University has a law faculty and there are lawyers trained in civil as well as Shariah law. But there isn’t anyone I know of tracking how many licensed attorneys are practicing in the country. And outside of the major cities, legal disputes might be handled by tribal councils of district or provincial authorities.”

A young girl waits to be fitted for shoes that were

among the supplies.

SHARED JOURNEY

While overseas, Deramus has been sharing his experiences with others in e-mailed dispatches to colleagues on SoloSez, the ABA’s e-mail discussion board for solo and small-firm practitioners.

In those dispatches, DeRamus doesn’t fixate on his daydreams for the country. Flying at night over Afghanistan is like flying over the ocean with nothing but darkness below, DeRamus says. But by day, he is awed by the country’s beauty. He believes Afghanistan could be a magnet for skiers and nature lovers —if the country were not laced with landmines and racked by war.

Instead, he focuses on small moments of human grace. In one dispatch, for instance, he praises the courage of a female doctor who wore a burka to operate when the Taliban ruled. She’s now health director for her province, he reports. In another, he cherishes an incident on an isolated road, where a PRT was stranded for five days in a perilous, remote province.

“They were overrun,” DeRamus says, “not by any insurgents, but by ordinary people offering them help, comfort and food.”

Web extra:

Sterling DeRamus’ e-mail dispatches from Afghanistan.