When artists gain fame after death, questions can arise over copyright ownership

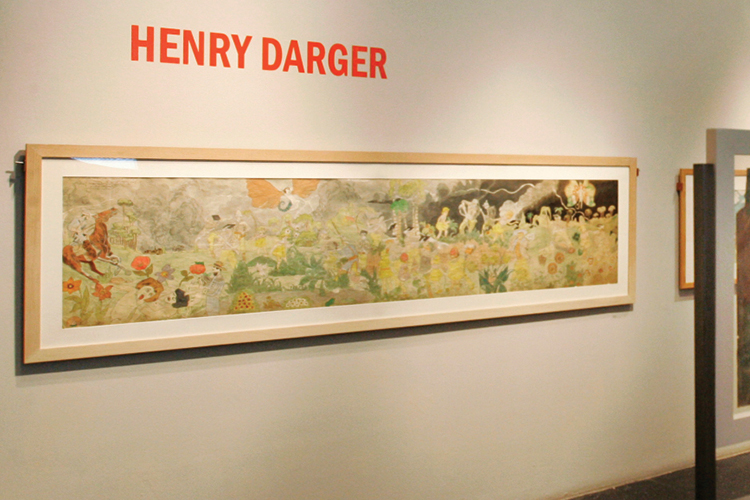

Henry Darger's work displayed at a 2008 Chicago exhibition. (AP Photo/Charles Rex Arbogast)

Until recently, Christen Sadowski did not know she had a long-lost relative named Henry Darger who died 50 years ago—or that he’s considered one of the most significant outsider artists of the 20th century.

“It’s a little heartbreaking—the demons he must have dealt with, in terms of the way it came out within the artwork,” says Sadowski, a 54-year-old finance employee who lives in Chicago’s western suburbs.

She now heads the newly established estate of Henry Joseph Darger Jr., which last summer filed a federal lawsuit in the Northern District of Illinois with hopes of acquiring Darger’s works and the copyrights to them.

The case—entwining state-level probate court and federal copyright law—is the latest legal fight pitting family members of an artist who died without a will against parties accused of commercially exploiting the artist’s work. It’s also a noteworthy case for collectors or entrepreneurs who have obtained an artist’s physical work and may then be tempted to try to profit from its underlying intellectual property. They are different things.

These same legal issues arose following the 2009 death of Chicago street photographer Vivian Maier, who left no will or apparent heirs. The retired nanny became famous posthumously, as her incredible story circulated and after some buyers of her prints and negatives began reproducing her work.

A similar dispute also is emerging in Arkansas. Relatives of Heber Springs photographer Mike Disfarmer are trying to gain control of his negatives and copyrights through probate action. Although Disfarmer died in obscurity in 1959, he is celebrated today for his black-and-white portraits of locals.

The Darger case likewise comes after decades of silence. Sadowski—the artist’s first cousin three times removed—says she understands why some observers might wonder why the family is only now trying to claim his legacy.

“It doesn’t make our responsibility as a family any less immense,” she says.

Born in Chicago in 1892, Darger spent some of his childhood in an orphanage. As an adult, he worked a series of menial jobs. For decades, he privately toiled on voluminous writings and otherworldly paintings of children. His words and images, including his magnum opus, an illustrated novel of more than 15,000 pages titled In the Realms of the Unreal, have been described as everything from creepy to sublime.

Darger died intestate in 1973. His longtime landlords, Nathan and Kiyoko Lerner, said their tenant bequeathed his works to them, and they are credited with saving Darger’s extraordinary art and sharing it with the world. (Nathan Lerner died in 1997.)

“Darger was an unknown at the time of his death and buried in a pauper’s cemetery in Des Plaines, Illinois,” Kiyoko Lerner said in a 2022 affidavit explaining how she and her husband looked after their reclusive tenant and acquired his creations. “However, solely through my and my husband’ [sic] efforts, his works have become part of museum collections in Chicago, New York, Paris and Switzerland, and Darger is now recognized throughout the world.”

The artist’s relatives offer a different perspective in their federal lawsuit and related court filings. They say the Lerners took Darger’s works without any legal authority, and they accuse Kiyoko Lerner of disassembling bound volumes for distribution and sale and of registering several copyrights. One page alone from Realms fetched $675,000, the complaint notes.

Darger’s relatives also say Kiyoko Lerner was aware that the emergence of Darger family members could be a potential problem. Lerner began collaborating with a Darger biographer in the mid-1980s on the condition “they would not track down any possible Darger relatives—so as to avoid a fight contesting the rights to the artwork,” one recent filing says.

It is this aspect of the Darger story that vexes photo collector Ron Slattery, who was a witness to the frenzy that developed around Maier more than a decade ago. Slattery legally acquired several of Maier’s prints and negatives at auction but never reproduced any of them, he says, upon the advice of his attorney, because there were too many legal questions.

“Somebody always owns the copyright,” Slattery says. “It’s never up in the air. It’s never just floating there. And you just don’t grab it like a balloon at the fair.”

Virginia-based intellectual property lawyer David Deal also had questions. In 2014, he filed a petition in Cook County, Illinois, probate court seeking recognition of Maier’s overseas heirs. The estate of Vivian Maier that resulted holds the copyright to the late photographer’s works and currently is overseen by the Cook County public administrator.

In 2017, the estate filed suit against one North Carolina collector who allegedly sold prints of Maier’s unpublished photographs for “well over $1,000 each, and often much higher.” Court records indicate the case was set to be dismissed. Both sides declined comment when asked whether a settlement was reached.

Slattery and his wife, Fawn, have become known as advocates for the legacies of outsider artists whom they feel have been mistreated in death. They say they easily found leads to surviving Darger relatives on the artist’s paternal side and contacted them in 2019.

Through the federal lawsuit, the family members hope to recover Darger’s physical works and to have the court recognize the estate as copyright holder. In addition, the suit seeks past profits and damages from Kiyoko Lerner, Nathan Lerner’s estate and a foundation in the Lerners’ name.

Kiyoko Lerner’s Chicago-based attorney, David W. Hepplewhite, declined to be interviewed but argued in a motion to dismiss that the lawsuit comes too late under the legal doctrine of laches. He also raises questions about which federal copyright law may apply to Darger. The motion to dismiss was denied March 28.

Two U.S. copyright systems straddle the 20th century. Prior to the late 1970s, copyright law was considered less favorable to artists, who had to affix copyright notice to a published work to keep it from the public domain. Artists could also register the work for an initial 28 years of copyright protection and later extend the copyright before it expired.

Unpublished works from this earlier period were protected under a later copyright act, says copyright expert Aaron J. Moss, a partner at Greenberg Glusker in Los Angeles.

“It had what was considered to be common-law protection at that time. And once the 1976 act was passed, that was converted to statutory protection,” says Moss, not speaking about any particular case.

Under the latest copyright provisions that govern works created today, artists and their heirs enjoy copyright protection lasting 70 years from the artist’s death. Copyright is automatic with the very creation of a work, although artists can formally register it with the government.

Stanford Law School professor Paul Goldstein, who has written a five-volume treatise on U.S. copyright law, says he does not recall a precedent-setting case with the peculiarities of the Darger lawsuit that may inform how it plays out.

The circumstances behind the reopened estate of photographer Disfarmer have their own nuances.

Disfarmer died intestate and his belongings were liquidated more than 60 years ago, before he rose to fame in the 1970s, thanks in part to a book showcasing his work. Today, original Disfarmer prints can go for several thousands of dollars each.

Fred Stewart, a 65-year-old great- grandnephew of Disfarmer, has been named administrator of the estate. Nearly 100 relatives organized after learning about their famous family member through the efforts of Ron and Fawn Slattery and Deal.

Stewart says the family suspects Disfarmer’s assets may not have been handled properly after his death. No lawsuit has been filed, and Stewart talked in conciliatory tones when asked about the estate’s long-range plans. “We do not want to hurt anybody, and we do not want to make anybody look bad,” he says.

Observers say the similar but unique sagas involving Darger, Disfarmer and Maier should serve as guideposts for the art world moving forward—for when works of the next late, great American creatives are discovered at auctions, flea markets or garage sales.

The purchaser of a painting or photograph may own the physical object but not the underlying art or image. They don’t get carte blanche to do anything they want, Deal says.

“That is never an option. Somebody is always the IP holder,” he says.

Updated April 6 to note that Kiyoko Lerner’s motion to dismiss was denied.

This story was originally published in the April-May 2023 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Finders Keepers? When artists gain fame after death, questions can arise over copyright ownership.”