Lincoln and Davis: A Friendship That Made History

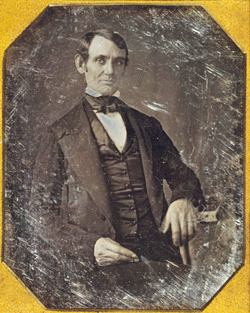

The earliest-known photograph of Abraham Lincoln at age 37, as congressman-elect from Illinois.

After serving a single term in the U.S. House of Representatives as a member of the Whig Party, Abraham Lincoln returned to Springfield, Ill., in the spring of 1849 and resumed his law practice. Lincoln was away from home for long stretches, as he joined other members of the bar in traveling between remote courthouses throughout the 8th Judicial District, which covered 14 central Illinois counties and 500 miles. It was not uncommon for Lincoln to be out “riding circuit” for three-month stretches twice each year.

Presiding Judge David Davis went out on a regular rotation. At county seat inns, the lawyers often slept two in a bed—except for the 300-pound Davis, who, for obvious reasons, required his own berth. Dinner at an inn often was a community affair that included not only lawyers and judges but also witnesses, jurors, litigants and sometimes even prisoners out on bail. Davis and Lincoln enjoyed those evenings, swapping jokes and stories. The friendship they forged traveling between the remote county seats of the 8th District would have a profound impact on U.S. history.

That friendship thrived despite the fact that they came from dramatically different backgrounds. Davis was well-educated—he graduated from Kenyon College in Ohio and studied law at Yale. Lincoln was virtually unschooled. He was, however, extremely self-educated. After he returned from Washington, he plunged into studies of mathematics, poetry and astronomy. He read Euclid and Shakespeare, and Byron and Burns.

Read all the articles in our special report:

- An Inescapable Conflict

- Lincoln and Davis: A Friendship That Made History

- Secession: How the South Nearly Won

- Lincoln’s War Powers: Part Constitution, Part Trust

- The Dawn of a Republican Court: Lincoln’s Justices

- The End of War and Slavery Yields a New Racial Order

- The Conspirators: Tried by Military Commission

- Gallery: Civil War-Era Legal Figures

As Lincoln gradually gained political prominence, his inner circle of supporters included many Illinois lawyers, including Davis. Early in 1860, many of those supporters thought a prudent timetable called for Lincoln to run that year for Illinois governor, for the U.S. Senate in 1864, and then make a run for the presidency representing the Republican Party in 1868. Davis, on the other hand, favored an immediate run for the presidency.

WILD SCENE IN THE WIGWAM

In early May, the Illinois Republican convention chose Lincoln as its choice for the presidential nomination. Lincoln made sure that Davis was one of the delegates-at-large to the national convention that started in Chicago on May 16.

While Lincoln stayed in Springfield, Davis took command at his candidate’s headquarters at the Tremont House hotel, where he established the campaign strategy: Block the bandwagon for Sen. William H. Seward of New York, line up at least 100 delegates for Lincoln on the first ballot, gain momentum on the second, and win the nomination on the third.

Davis dispatched his troops to woo delegates. He privately visited the critical delegations from New Jersey, Indiana and Pennsylvania, where he allegedly promised Cabinet seats to their leaders in exchange for support for Lincoln—although the historical evidence is hazy. It seems likely, though, that Davis ignored a telegram from Lincoln stating: “Make no contracts that will bind me.”

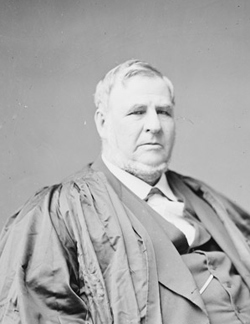

David Davis (cir. 1870-1880). Lincoln’s mentor and political supporter, later became a U.S. Supreme Court justice.

On the second ballot, Seward was ahead of Lincoln by only four votes, but then the Ohio delegation suddenly announced a change of four votes from its native son, Gov. Salmon P. Chase, to Lincoln. The convention hall—a temporary wooden structure called the Wigwam—erupted. Davis had packed in 5,000 vocal Lincoln supporters.

Davis was the architect of Lincoln’s nomination and election. And he accompanied Lincoln to Washington, D.C., though he didn’t stay there after Lincoln’s inauguration. Instead, he returned to Illinois and began riding circuit again. (Lincoln’s key opponents at the Republican convention joined his Cabinet or took other key posts in the administration.)

Lincoln called Davis back to Washington in late 1862, when he nominated him to the U.S. Supreme Court on Dec. 1. Davis was quickly ratified by the Senate and took his oath on Dec. 10 as an associate justice, just in time to hear arguments in a crucial test of Lincoln’s war powers.

On March 10, 1863, the court ruled 5-4 in the Prize Cases that the president did not require authorization from Congress to impose a blockade against the Confederacy after the shelling of Fort Sumter in April 1861. Davis was a member of the five-member majority that gave Lincoln a critical legal victory.

By the end of the war, there was just one last service that Davis could perform on behalf of his old friend. After Lincoln died on April 15, 1865, from an assassin’s bullet, Davis was executor of his estate.

Arthur T. Downey of Washington, D.C., has lectured at the Smithsonian Institution on legal issues in the Civil War and on Abraham Lincoln. He is the author of Civil War Lawyers, released by ABA Publishing in 2010.