People Like Their Own Ideas

Illustration by Edwin Fotheringham

“I just don’t get it!” said Marty. “This is the seventh different way I’ve put my opening statement together, and not once has it sounded persuasive when we replayed the video. What am I doing wrong?”

Marty Sanchez has a big employment discrimination trial coming up in Judge Standwell’s court. He asked Angus and me to help him get his case off to a good start. This was the second evening we spent working on his opening.

“I don’t think the problem is with your organization,” Angus said. “The biggest stumbling block is your language.”

“My language?” said Marty. “I haven’t used a single word the average eighth-grader wouldn’t understand.”

“True,” said Angus. “But you use far too many modifiers—adjectives and adverbs. And words and phrases of condemnation and judgment, like sexism, racism, blatant discrimination and systematic exclusion. They’re terms you’re using to tell the judge and jury how to decide your case before they’ve heard any of the facts.

“That’s what I’m supposed to do,” said Marty. “Persuade. After all, this is opening argument.”

“The term is opening statement,” said Angus. “Only the media and a few big-firm ‘litigators’ call it opening argument. And besides, no matter what you call it, you shouldn’t argue in your opening—whether the judge lets you do it or not.”

“That’s ridiculous,” said Marty.

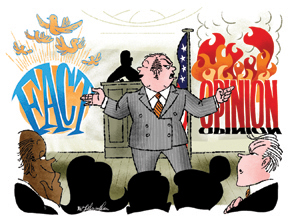

“No, it’s not,” said Angus. “When you argue a point to anyone—judge, jury, neighbor or friend—before they know the facts, they instinctively resist accepting your spin on what it’s about.

You’re telling them how to think—and people don’t like to be told how to think. They want to reach their own conclusions.

“Facts, not opinions, are what persuade,” said Angus, “because people like their own ideas.

“And that means you should show, not tell.

“When you put the facts together without any editorial comments—verbal pushing, shoving or arm-twisting—it’s the story that engages the minds of the listeners. It impels them to reach their own evaluation of the facts. That’s what ‘show, not tell’ means. It’s the magic behind the world’s best writing and most enchanting stories.

“But the hard part is, it takes serious self-discipline to keep from interrupting a beautiful verbal picture to give the listeners your personal spin on the facts.

“When you give in and tell them how to think, it tears a hole in the picture that lets all the magic run out,” said Angus.

WHERE’S THE MAGIC?

“But if you take out all the spicy adjectives and adverbs,” said Marty, “where does the magic in the story come from in the first place?”

“Tension,” said Angus. “Tension is at the heart of every interesting story. When opposing forces collide, people want to see how it plays out. They’re not neutral observers. They take sides.

Almost from the very beginning, they’re pulling for one party or the other.”

“How can they take sides so soon—before they’ve heard the whole story?” said Marty.

“There are two factors at work,” said Angus, “each one worth a lifetime of study.

“One is the ‘rush to judgment.’ People feel uncomfortable whenever they don’t know what to do. So when they’re confronted with a new situation, the first thing they do is subconsciously search through the thousands of layers of stories in their minds to see if it’s like something they’ve encountered before. And if they find one that seems to fit, it helps protect them from feeling the inadequacy—of not knowing what to do or say.”

“The second factor is the sense of injustice,” said Angus. “It’s probably the single most powerful force in the courtroom.”

“Injustice?” said Marty. “What about justice?”

Angus smiled. “Thanks. That was right on cue.

“The problem with justice is no one really knows what it is. It’s an indefinable ideal—not a definable idea.

“But while we may not be able to give a good definition of justice, injustice—unfairness—is real. Everybody recognizes it when they see it.

“Injustice is one of the most powerful forces in the world. As legal philosopher Edmond Nathaniel Cahn said, ‘Injustice has the power to stir people’s blood.’ ”

Marty looked transfixed. “I never thought of ideas as being so exciting,” he said. “But how can you possibly put them all together? How can you convey the idea of a serious injustice that’s part of a simple story loaded with tension without telling anyone how they’re supposed to react to it?”

“One of the easiest—and most effective—ways to do all that is to foreshadow—drop a hint at the beginning about what’s to come,” said Angus. “Listen to the first two sentences of the plaintiff’s opening statement in a personal injury case:

“ ‘Ladies and gentlemen, this is a case about a young woman’s eyes.

“ ‘If you had been at the corporate headquarters of the Mid-West Conveyor Belt Manufacturing Co. in Chicago on the 14th of June 2006, you would have seen seven corporate officials be given an opportunity to prevent a tragedy.’ ”

“That’s powerful,” said Marty.

“What happened to the young woman?” said Angus.

“Something bad,” said Marty. “She’s probably blind. At least in one eye—maybe both.”

“Who’s to blame?” said Angus.

“The corporate officials could have prevented it, but they obviously didn’t,” said Marty.

“Who told you that?” said Angus.

“Nobody. It just makes sense from what we know.”

“Does that mean there’s been an injustice? Has she been wronged?” said Angus.

“It’s hard to think about it any other way,” said Marty. “And there’s another thing. I actually felt I saw those corporate officials have the chance to save this woman’s eyes. I even have a picture in my mind of the corporate headquarters with its thick, red carpets and floor-to-ceiling windows with a view of Lake Michigan.

“How do you do that?” said Marty. “Make an unholy bargain with the forces of darkness?”

USE VISUAL LANGUAGE

Angus laughed. “It’s all based on simple principles,” he said.

“Visual language is an implied invitation to see something for yourself. Even though it was a conditional, past-tense statement, the second sentence was an invitation to see the corporate officials in their Chicago headquarters. A normal imagination on the part of the juror does the rest of the work, like adding big windows and thick, red carpets and maybe even walnut paneling.

“It works partly because 70 percent of the neurons in the normally sighted human brain are devoted to interpreting visual images. And the scientific studies show you can actually access this part of the brain with spoken and written words.

“Think about what that means for a moment,” said Angus.

“Say you’ve got a highway safety engineer on the witness stand who’s going to testify about what caused a bridge to collapse. You say, ‘Dr. Webster, take us with you to the Missouri River. Let us look at this bridge through your eyes. What’s the first thing you notice?’ ”

“Can you do that?” said Marty.

“I asked a question like that in a trial in Oxford, Miss.,” said Angus, “and the Detroit defense lawyer objected.

“The judge said, ‘What’s your objection, son?’

“He had to come up with something, so he said, ‘It’s too effective!’

“And the judge said, ‘That ain’t an objection in Mississippi, son. Overruled.’ ”

“What a great story,” said Marty.

WALK THE TALK

“Tell me something,” said Angus. “do you think it would have had the same impact if I had just said yes when you asked, ‘Can you do that?’ ” Marty’s eyes opened wide. “Good grief!” he said. “You do this all the time! You’re even doing it with me.”

“Of course,” said Angus. “Effective communication skills aren’t something you just put on like your good suit when you go to court. You need to use them all the time so you’ll be comfortable with them.”

“Do you really think I could learn how to use these ideas?” said Marty.

“Why not?” said Angus. “Every one is a natural part of the English language. Their effects are subliminal. You never notice them when you’re concentrating on the content of what people say.”

“Nuh-uh,” said Marty. “I picked up every one.”

“That was because I pointed them out and we talked about them,” said Angus. “These techniques are like some of Harry Potter’s friends, who are completely transparent unless you call them out by name.

“Did you notice Mr. Present Tense at work even though I didn’t mention him?” said Angus. “He makes things seem as if they are happening now.”

“I would have noticed that,” said Marty.

I had left the video recorder on while Angus was giving his critique and ran it back to where he said, “Dr. Webster, take us with you to the Missouri River. Let us look at this bridge through your eyes. What’s the first thing you notice?”

“Can I have that videotape?” said Marty.

“It’s for you,” said Angus.

James W. McElhaney is the Baker and Hostetler Distinguished Scholar in Trial Practice at Case Western Reserve University School of Law in Cleveland and the Joseph C. Hutcheson Distinguished Lecturer in Trial Advocacy at South Texas College of Law in Houston. He is a senior editor and columnist for Litigation, the journal of the ABA Section of Litigation.