July 7, 1865: Lincoln assassination co-conspirators hanged

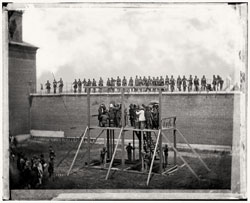

Photo by Alexander Gardner/Library of Congress

In the early morning hours of April 15, even as President Abraham Lincoln lay dying from a gunshot wound to the head, local police in Washington, D.C., arrived at a boardinghouse in the city’s Northwest quadrant in search of John Wilkes Booth. Booth and other Confederate sympathizers had been known to frequent the white painted-brick house, as well as a tavern just outside the city, both owned by widow Mary Surratt.

While the attack on Lincoln was being carried out at Ford’s Theatre, a simultaneous attack on Secretary of State William Seward in his home left the government in a frenzy over the potential extent of the conspiracy. Teams of law enforcement officers—first local, then federal—focused on the comings and goings at the Surratt house. At first, they found nothing. But two days later, federal officers returned with orders to search the premises and arrest everyone staying there. An abundance of circumstantial evidence was found, but a chance meeting helped seal the suspicion that Surratt was part of the plot. As she was being led away, a man showed up seeking refuge, clearly in disguise. Surratt said she didn’t know him, but it turned out to be Lewis Powell—identified as the man who’d stabbed Seward. By the time the roundup was done, nine co-conspirators were arrested, all of whom had some connection to Surratt.

By order of President Andrew Johnson (another target of the conspiracy), the nine, though civilians, were tried by a military commission. Their trial was held at the Washington Arsenal, a military outpost on the Potomac River. The proceedings began May 9 and ended June 28. When the sentences were handed down on June 30, four were sentenced to death: Surratt; Powell; Powell’s accomplice, David Herold; and Johnson’s would-be assassin, George Atzerodt.

Pleas for Surratt’s life, including one by five of the sentencing judges, went unheeded by President Johnson. On the morning of the execution, marshals attempting to serve a writ of habeas corpus were turned away at the gates of the arsenal. Johnson canceled the writ under the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863.

Though Surratt (sitting under the umbrella at far left) continued to profess her innocence, she and the three others were led to a hastily constructed gallows on the grounds of the arsenal. After a process that took barely 20 minutes, Surratt and her former boarders were dead.