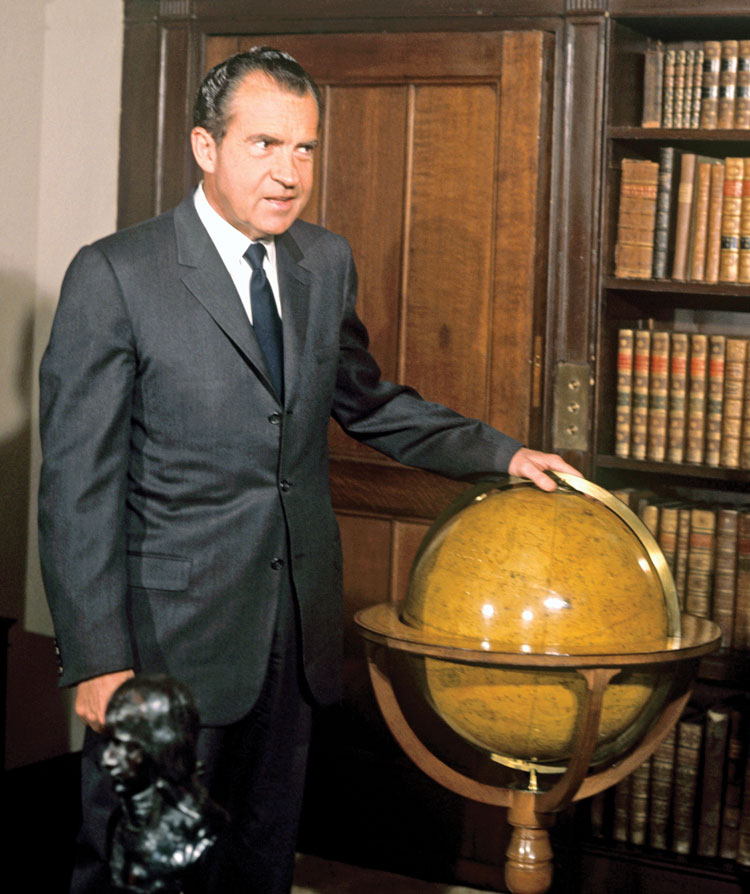

A new book looks at how a law firm stint revived Nixon's political and presidential prospects

NEXT STOP: SPAIN

Associated Press

Instead, Nixon Mudge turned its attention to Spain. The firm went after a group of Trujillo heirs living in Madrid, including the biggest fish of them all: Ramfis Trujillo. The eldest son and heir apparent to his father, Ramfis parlayed his lifelong career in the Dominican military (his father had him appointed a major at the age of 3) to succeed his assassinated father as leader of the Dominican Republic in 1961.

However, before he could bestow upon himself an outlandish title like “Defender of the Dominicans,” he found himself out of power and forced into exile. He ultimately settled in Spain, where he lived an extravagant lifestyle under the protection of that country’s strongman, Generalissimo Francisco Franco. The St. Petersburg Times reported that Ramfis had about $60 million stashed away in his account in Spain and mentioned that Nixon was working on trying to get some of it for his clients.

On May 5, 1965, Nixon took a well-publicized trip to Geneva to meet with Swiss Department of Justice officials. According to an internal firm memo, the trip was necessary because Nixon Mudge lawyers believed that, unlike with Radames Trujillo, the Swiss courts had been dragging their feet when it came to adjudicating the complaint against the Madrid heirs.

“The present inaction, on a complaint filed with impressive supporting fact, by an American bank and American citizens (or residents) might lead one to wonder if the Swiss laws on secrecy in the banks are not construed to provide a safe haven for embezzlers and receivers of stolen goods,” the internal memo stated. The memo also noted that it was vital to have the threat of an “actively prosecuted” criminal case against the Madrid heirs to provide the kind of leverage necessary to get the Miami heirs their fair piece of the estate.

To that end, a few days after the Geneva meeting, Charles Celier, European counsel at Nixon Mudge’s Paris office, and Lodge met with Spanish officials to pressure them to extradite the Madrid heirs to Switzerland. According to a letter from Lodge to Nixon, the Spanish authorities were sympathetic, but they stated outright that “the basis for intervention did not seem entirely clear.”

Spain’s stance only hardened in the next year. In a letter dated April 2, 1966, Spain’s undersecretary of foreign affairs, Pedro Cortina, told Lodge “there was no possibility on the part of Spanish administrative authorities in a matter strictly of a private order.” Cortina said the only way Spain would get involved would be if it received an extradition order from Switzerland, and that had not happened.

Additionally, Cortina stated that Spain had an interest in maintaining its neutrality in this issue because of the Madrid heirs’ status as refugees. “The desire that the Spanish authorities should intervene in the matter for the purpose of reaching a friendly settlement with the object of avoiding the publicity which repeatedly had taken place in the world press was not at any time considered appropriate for the Spanish government,” Cortina said.

The result was somewhat ironic for Nixon. An internal firm memo had emphasized that “there is strictly nothing political about this case” and that it was “strictly a family feud.”

Of course, things weren’t that simple. After all, Trujillo may have been a bloodthirsty, megalomaniacal despot, but from the point of view of many American officials, he was our bloodthirsty, megalomaniacal despot. He had been an important counterweight to Castro in the Caribbean, and a friend to American business leaders like aviation executive William D. Pawley, who had gotten rich by doing business in the Dominican Republic. Without him, the Dominican Republic could be the next domino to fall, and the last thing the White House wanted was another Castro in its backyard.

“If Castro is going to support revolution in the Dominican Republic, it is time for us to go to the source of the problem,” Nixon told House Minority Leader Gerald Ford in 1965. “I am not calling for war on Castro. I am saying he should be warned, and this cannot be a one-way street.”

BUILDING BONA FIDES

As for Nixon, it made sense why he would want his name in the papers in relation to the Dominican Republic and Trujillo. It reaffirmed his anti-Communist credentials and reminded voters of his foreign policy knowledge. Most importantly, his representation of Trujillo’s offspring sent a signal that he remained interested in the fate of the republic as well as the U.S. businesspeople who were heavily invested there.

With plants in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, Pepsi’s Kendall had long been concerned about the region and had gone so far as to send Lyndon Johnson a letter heaping praise on the president for acting boldly and decisively by sending the military into the Dominican Republic. Kendall even tried to forge an unofficial alliance between Johnson and Nixon, bringing up Nixon’s solid and outspoken support for the intervention.

“After listening to Nixon discuss both the Vietnam and Dominican Republic situations,” Kendall wrote, “it occurred to me that since there is such a problem of selling your policies to certain segments of the American population, as well as some of our friends abroad, you might want to consider using him as a spokesman in this country and abroad to help sell your policies.”

In fact, Nixon was not only supporting the Johnson administration’s stance; he was using the Dominican intervention as a wedge to drive between liberals and that administration. In speeches he would alternately commend Johnson and Vice President Hubert Humphrey for taking swift, decisive and necessary action while criticizing their liberal base for opposing the move. “History will be kinder” to Humphrey than his fellow liberals, Nixon said mischievously during a speech before the 46th U.S. Junior Chamber of Commerce Convention in 1966.

But for Kendall and others like him, who were desperately concerned about the fate of Latin America, Nixon’s words were music to their ears. And like many of Nixon’s clients and business friends, they did not forget Nixon when it came time for the 1968 campaign.

Nixon in New York, published in April by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, is the first book written by Victor Li, an assistant managing editor at the ABA Journal. A former prosecutor in the Bronx, Li came to the Journal as a reporter in 2013 after stints with Law Technology News, The American Lawyer and Litigation Daily.

This article was published in the May 2018 issue of the ABA Journal with the title "Nixon in New York: A new book looks at how a law firm stint revived his political and presidential prospects."