Unequal Justice: U.S. Trails High-Income Nations in Serving Civil Legal Needs

Rebecca Sandefur: “There’s a disagreement over how much need there is because there’s no good, contemporary national data. ….We just know there’s a lot.” Her next survey will look at access to the civil legal system in the Midwest. Photo courtesy of L. Brian Stauffer.

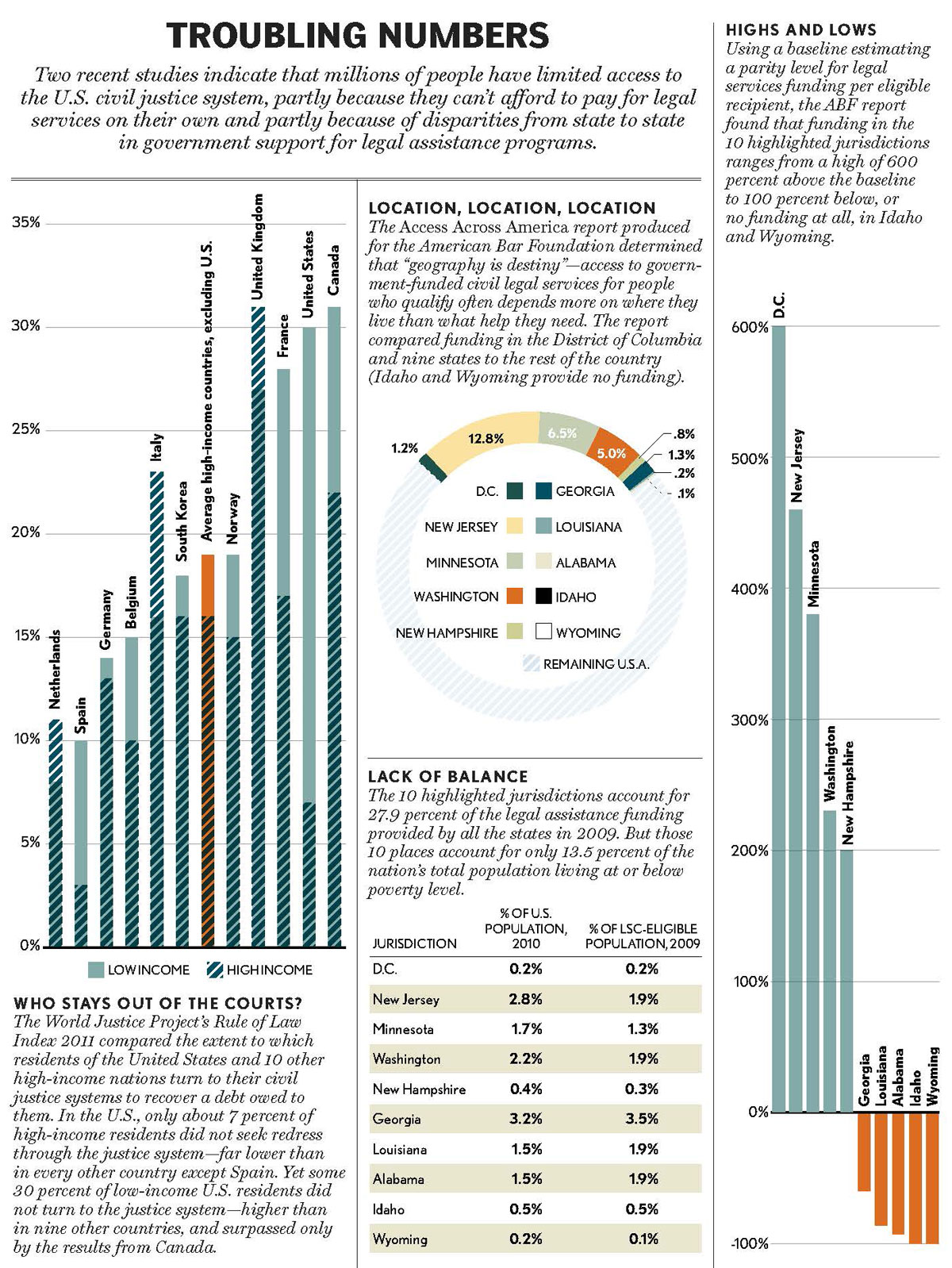

Two recent studies provide news good and bad for the U.S. legal system. The good: The United States’ civil legal system is one of the best in the world, according to the results of the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index 2011.

And the bad? According to this same study, millions of Americans can’t use this fine system because they can’t afford it. They have legal rights—to child support, Medicare benefits or protection against an improper home foreclosure—but they find these rights meaningless because they can’t enforce them.

“The U.S. legal system is similar to its medical system; in many aspects it is the best in the world, but many people don’t get any services at all,” says Juan Carlos Botero, director of the Rule of Law Index project.

A plethora of government and volunteer programs provide free legal aid, but they are overstretched. “Any local legal aid office will tell you that at least two-thirds of those who walk through their doors aren’t getting help because there aren’t enough resources,” says H. Ritchey Hollenbaugh, chair of the ABA Standing Committee on the Delivery of Legal Services and a partner at Carlile Patchen & Murphy in Columbus, Ohio.

To make matters worse, the system for providing free legal services is a mess. There is “an enormous diversity of programs and provision models with very little coordination at either the state or the national level,” according to Access Across America, a 2011 report (PDF) authored by Rebecca L. Sandefur and Aaron C. Smyth and funded in large part by the American Bar Foundation. As a result, the report states, poor individuals’ access to assistance is “characterized by large inequalities both between states and within them. … The services available to people … who face civil justice problems are determined not by what their problems are or the kinds of services they may need, but rather by where they happen to live.”

QUALITY QUEST

It’s not easy to determine the quality of a country’s legal system, but that hasn’t stopped the World Justice Project, which was founded in 2006 by the American Bar Association and other organizations representing various disciplines but is now an independent not-for-profit organization. The WJP interviewed more than 2,000 legal experts and 66,000 laypeople in 66 countries about 52 factors related to their nations’ adherence to the rule of law. The organization then compiled the results in its latest annual Rule of Law Index, providing a multifactor, quantitative measure of the various countries’ adherence to the rule of law.

“The United States obtains high marks in most dimensions of the rule of law,” the index states. “The country stands out for its well-functioning system of checks and balances and for its good results in guaranteeing civil liberties,” and “the civil justice system is independent and free of undue influence.”

But the study also found some significant problems, noting that “the civil justice system … remains inaccessible to disadvantaged groups,” “legal assistance is expensive or unavailable,” and “the gap between rich and poor individuals in terms of both actual use of and satisfaction with the civil courts system remains significant.”

When comparing nations on accessibility of civil justice, the survey ranked the U.S. 11th out of 12 countries in North America and Western Europe. Among high-income nations worldwide, the U.S. ranked 20th of 23. Among its high-income peers, the U.S. beat out only Italy, Croatia and Poland.

A big reason the U.S. received these disappointing scores was because so many of its residents have no access to legal counsel. When comparing nations on the ability of their people to obtain legal counsel, the U.S. scored 50th out of all 66 nations surveyed.

American lawyers don’t come cheap, which may be why rich individuals use the civil legal system to resolve their disputes significantly more often than do poor people. When facing a common civil dispute—an unpaid debt—46 percent of high-income individuals file a lawsuit while only 33 percent of low-income individuals do the same, according to the survey.

More troubling, however, is the percentage of people who don’t try to get justice. Seven percent of high-income individuals take no action to pursue money they are owed, while 30 percent of low-income individuals don’t do anything, the survey found.

“The vast majority of the legal problems faced by (particularly poor) Americans fall outside of the ‘rule of law,’ ” writes Gillian Hadfield, a professor of law and economics at the University of Southern California, in a 2010 law review article, “Higher Demand, Lower Supply? A Comparative Assessment of the Legal Resource Landscape for Ordinary Americans.”

“High proportions of people … [are] simply accepting a result determined not by law but by the play of markets, power, organizations, wealth, politics and other dynamics in our complex society,” her article continues.

H. Ritchey Hollenbaugh: “Hard economic times increase the need for legal assistance.” Photo by Michael McElroy.

THE JUSTICE GAP

Other high-income nations do a much better job of providing those at all economic levels with access to civil justice. When confronted with a civil legal problem, 30 percent of low-income Americans give up and seek no legal redress, compared to 7 percent of high-income residents. In other industrialized nations the difference is not so large, with 19 percent of low-income and 16 percent of high-income residents taking no legal action, on average, according to the Rule of Law Index 2011.

“The gap between low- and high-income people’s use of the civil legal system is much higher in the U.S. than in other high-income nations,” Botero says. “This gap is significant and is consistent year after year” for the last four years in which the index has been in existence.

U.S. legal aid programs are supposed to close this gap but they don’t—in large part because these programs are underfunded. A study by the Legal Services Corp. based on surveys of legal needs in nine states found that, as a result of resource limitations, LSC-funded programs had to turn away half the eligible people seeking assistance. People living in households with incomes at or below 125 percent of the federal poverty level are eligible for LSC aid.

Since that 2005 study, the situation has gotten worse as the demand for legal aid has jumped. “Hard economic times increase the need for legal assistance,” notes Hollenbaugh, who is also president of the Ohio Legal Assistance Foundation.

Meanwhile, Congress has severely cut back funding for the LSC, which distributes federal grants to independent nonprofit legal aid programs throughout the United States and its territories. Fiscally strapped state and local governments also are spending less on legal aid. (President Barack Obama included $402 million for the LSC in the proposed fiscal 2013 budget he recently sent to Congress. That is a 15.5 percent increase over the LSC’s current $348 million budget, but still $68 million less than the corporation requested for next year. And there’s no guarantee what Congress will do.)

Other sources of funds are drying up, too. Legal aid programs often receive money from the interest on lawyers’ trust accounts, but interest rates have dropped substantially. Some states help fund legal aid through an extra fee on court filings, but “overall, court filings are down,” Hollenbaugh says.

As result, legal aid programs are being squeezed. “We face a perfect storm of reduced resources at a time of greater need,” says Jonathan D. Asher, executive director of Colorado Legal Services.

No one is certain precisely how many poor people are now doing without civil legal assistance. “There’s disagreement over how much need there is because there’s no good, contemporary national data on this. We just know there’s a lot,” says Sandefur, a sociology professor at the University of Illinois and the lead author of Access Across America.

One of the findings of Sandefur’s study is that unmet legal needs are far more prevalent in some parts of the country and for some groups. The study found the LSC does a pretty good job of distributing its funds fairly among the states; 59 percent of states receive LSC funds in proportion to the state’s LSC-eligible population. And while 18 percent of states receive fewer funds than they should and 24 percent receive more, “departures from parity for LSC funds are relatively small in magnitude,” the report found. (Percentages add up to more than 100 percent due to rounding.)

Individual states, by contrast, vary greatly in their funding of civil legal aid. Just six percent of states provide funding in proportion to their population. Thirty-five percent provide a much greater amount of funds— averaging 240 percent of what one would expect based on their population. The District of Columbia, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Hampshire and Washington state are among the leaders in funding civil legal aid.

On the other hand, 55 percent of states provide far less funding than expected, while 4 percent provide no funds. These states provide, on average, just 40 percent of the funding proportionate to their populations. Some of the states that provide the smallest amount of funds per capita are Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, Idaho and Wyoming; the latter two states provide no funds at all.

SPLINTERED AID

Even within a state, the availability of civil legal assistance varies widely, Access Across America found. That’s because many providers help only individuals in their locality. Many offer legal assistance to just certain types of individuals. For instance, one organization may help only the elderly, while another may help veterans, and a third may help the homeless. Many providers help with only specific types of civil law matters, such as evictions, debt or domestic violence restraining orders.

“Little coordination exists for civil legal assistance in the United States, and existing mechanisms of coordination often have powers only of exhortation and consultation,” the study states. “At the national level and within most states, civil legal assistance is organized much like a body without a brain: It has many operating parts, but no guiding center.”

The end result, the study declares, is “a fundamental absence of coordination in the system, fragmentation and inequality in who gets served and how, and arbitrariness in access to justice depending on where one lives.”

Some states are working to improve things. Washington state is a leader in this regard, providing a centralized, toll-free number for low-income individuals seeking civil legal aid. The phone service conducts intake, provides legal advice, and refers callers to appropriate legal service providers. Some other states offer centralized intake, but Washington has the nation’s most highly developed integrated system of civil legal assistance, Sandefur says.

But it is not enough to coordinate existing services, according to some experts. To better target legal aid, states should determine the populace’s civil legal needs and how people attempt to address these needs.

Unfortunately, conducting such a survey is expensive, and cash-strapped state governments are unlikely to pay for this.

That’s where Sandefur comes in. This year, she will be leading a survey funded by the National Science Foundation and the American Bar Foundation that will look at access to the civil legal system in a midsize city and its environs in the middle part of the U.S.

That survey, like the Rule of Law Index, may provide some disquieting information for the nation. Perhaps, however, that information will spur much-needed improvements in access to civil justice.

“A society dedicated to the rule of law needs to make legal representation a reality for more of those in need. It is both a professional and a public responsibility to make equal access to law a reality for more people,” Asher says. He adds that “the Pledge of Allegiance ends with ‘liberty and justice for all.’ We haven’t made that a reality.”

Graphics by Adam Weiskind