Can a town be a museum? A case may hinge on the precision of definitions

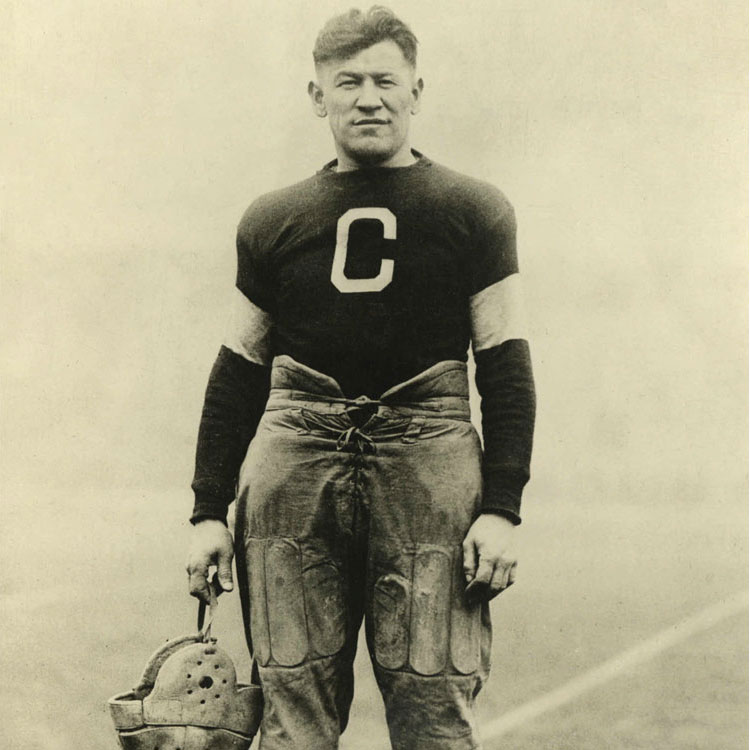

Photograph of Jim Thorpe by Heritage Auctions courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Last month, we saw that lexicography—the art of defining words for a glossary or dictionary—is an especially challenging task. In dictionary circles, it’s thought to take not only a special aptitude but also a great deal of training.

Yet all legal drafters are lexicographers in the sense that they’re expected to draft definitions in transactional documents, rules, regulations and legislation. Then, of course, judges must interpret these definitions in light of how the defined terms are actually used in a given legal instrument.

In patent drafting, there’s actually a doctrine that “every patentee may be his own lexicographer.” The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has said so in many cases, with slightly varying formulations.

The question I’d like to pose here is whether the usual meaning of a word being defined carries into a legal definition. This question arises with some frequency in litigation.

As a simple example, if we say “dog means cat,” does that mean that the sequence of letters d-o-g refers only to felines—that the word itself is an empty vessel to be filled with the defining words? Or are we saying that cats are deemed to be dogs, as well as all canines themselves (the ordinary meaning of dog)?

Granted, careful drafters distinguish between means and includes in preparing definitions. The latter simply stipulates that something else is embraced by the definiendum (the term being defined) in addition to whatever its ordinary sense is. So if the idea were to mean both dogs and cats, a more careful drafter would write: “Dog includes all cats” rather than “Dog means cat.”

On the other hand, you could just say dogs and cats when that’s what you’re referring to. An age-old recommendation in legal drafting circles holds that you mustn’t give counterintuitive definitions—even with includes. There’s a perhaps apocryphal story about a government regulation that once stated, “The term milk includes all citrus fruits.” That’s bad drafting. It would have been worse, of course, to say, “The term milk means citrus fruits.” Would that mean that milk, as we commonly understand it, would be excluded?

Museum mausoleum

Let’s consider an actual case—one decided a few years ago by the 3rd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals at Philadelphia. It involves one of the most beloved sports heroes of all time, Jim Thorpe.

Thorpe (1887–1953) was the Sac and Fox Nation member who became a renowned athlete as an Olympic track star, football player and baseball player. Shortly after he died (intestate), the members of his tribe gathered in his native Oklahoma to hold a traditional, two-day funeral rite. It was abruptly halted when Patsy, Thorpe’s third wife, arrived with law enforcement officers to take Thorpe’s body somewhere else.

After a year of negotiations, Patsy entered into an agreement with two small towns in Pennsylvania, where Thorpe had attended college. In exchange for the famous athlete’s remains, the two towns consolidated into a single borough under the name “Jim Thorpe.” The borough owned the land where the mausoleum would be located, and it would maintain the site. Thorpe had actually never been to the place chosen as his final resting place, and he had reportedly told family members other than Patsy that he wanted to be buried in Oklahoma. Yet Patsy was legally authorized to make the final decision, and Pennsylvania is what she chose back in 1954.

After the funeral there, many tribal ceremonies took place at the mausoleum. Family members visited the site over the years, and the Jim Thorpe Area Sports Hall of Fame worked to improve it.

In 1990, Congress enacted the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which gives tribes the power to request repatriation of cultural items, including human remains, if they are possessed or controlled by a federally funded museum.

Some 57 years after Thorpe’s death and 20 years after enactment of the graves protection act, Thorpe’s son John, from his second marriage, sued to exhume Thorpe’s body and return it to the Sac and Fox Nation. The evidence showed that John had waited so long because his sister opposed moving the body, and he couldn’t act till after she died. The trial court granted John’s request and, on summary judgment, ordered an exhumation and repatriation to Oklahoma.

The question on appeal came down to whether the borough of Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, qualified as a museum. That brings us to the statutory definition of museum: “any institution or state or local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives federal funds and has possession of, or control over, Native American cultural items.”

That’s pretty broad. Let’s stipulate that the borough receives federal funds. Is it a museum? The borough is certainly an institution that receives federal funds. By its very terms, the definition embraces universities and colleges. If a university can be a museum, surely a borough can be as well.

Yet should we disregard the ordinary meaning of museum altogether and consider only the defining words? Shouldn’t there be some consideration of preservation and curatorship for public exhibitions?

This article was published in the July 2018

Bryan A. Garner, the president of LawProse Inc., is a law professor, grammarian and lexicographer. His most recent book is Nino and Me: My Unusual Friendship with Justice Antonin Scalia.

Follow on Twitter @bryanagarner.