Will mandatory arbitration be banned beyond in workplace sex assault and harassment complaints?

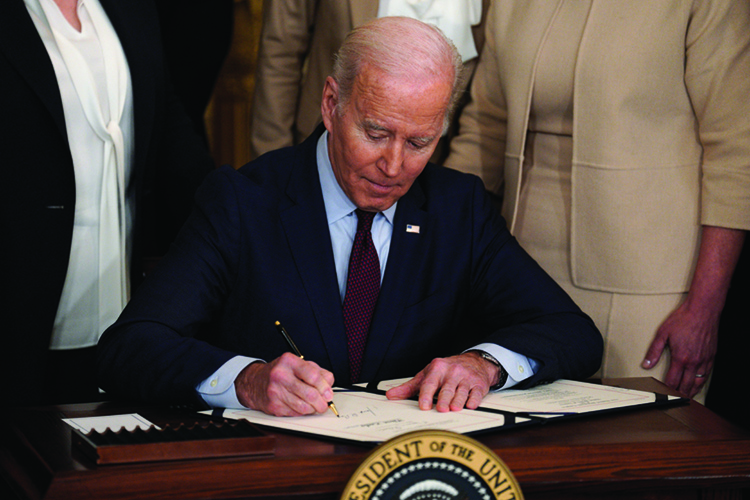

In March, President Joe Biden signed into law a bipartisan bill ending mandatory arbitration in workplace sex assault and harassment cases. Photo by Yuri Gripas/Abaca/Sipa USA(Sipa via AP Images).

Forced arbitration has long been a controversial practice in the United States.

According to an American Association for Justice report released at the end of October 2021, the number of employment disputes that were resolved in arbitration increased by roughly 66% from 2018 to 2020. The AAJ, a critic of forced arbitration, has argued that when workers (as well as consumers and patients) are forced into arbitration, they’re much more likely to lose since the system is stacked against them. In addition to not having a right to a jury, there’s no transparency, no right to discovery, and other essential checks and balances are missing from the process.

At least one component of forced arbitration, however, has now ended.

On March 3, President Joe Biden signed into law the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act of 2021. The law forbids employers from forcing employees into arbitration in cases involving allegations of sexual assault or harassment. It also prevents mandatory waivers of the right to bring sexual assault or harassment class action lawsuits or collective claims against employers. This is a rare issue that has garnered significant bipartisan support in Congress: The bill was passed by a vote of 335-97 in the House on Feb. 7 and then passed by voice vote in the Senate three days later.

Perhaps trying to build on that momentum, two weeks after Biden’s signature, the House approved the Forced Arbitration Injustice Repeal Act of 2022—which would eliminate forced arbitration in all employment, consumer and civil rights cases—on a much narrower, near-party line vote. The bill is currently in the Senate, where it was referred to the Judiciary Committee.

If it passes in the Senate this time and is signed into law, what will this mean for plaintiffs and companies? Could this spell the end for forced arbitration in the U.S.?

Pros and cons

Companies and employers have a strong incentive to keep mandatory arbitration in place for everything ranging from workers’ contracts to user service agreements.

“On one hand, it is a mechanism for parties to resolve disputes in a confidential manner that can be quicker and less expensive than resolving the dispute in court,” explains Amy Karff Halevy, a partner at Bracewell in Houston who represents employers in all areas of employment law.

She adds that ending mandatory arbitration in all instances would force companies to “rethink how they handle disputes not only with their employees, but also with customers—as the bill would invalidate any pre-dispute mandatory arbitration agreements related to antitrust, consumer and civil rights claims.”

Halevy and others argue that the FAIR Act would result in more disputes ending up in the court system, resulting in a severe backlog. In particular, it would open the door to many potential class action lawsuits—especially from consumers, who often don’t have a real choice to accept or decline mandatory arbitration provisions when purchasing goods and services.

Joe Brennan, professor at Vermont Law & Graduate School, points out that forced arbitration clauses are usually in the fine print of consumer contracts of everything ranging from cellphone user agreements to software licenses.

“For example, if you want a cellphone carrier, it’s a take-it-or-leave-it option—so you either agree to their terms, or you decline the use of their product,” he says.

A fear of increased class actions has been a major factor in keeping the mandatory arbitration structure alive.

“The opposition to the FAIR Act can be best summarized as the ‘anti-lawyer’ opposition—and it may sound funny, but the opposition is couched in the belief that the FAIR Act would produce more class action lawsuits to the benefit of the class action lawyers who bring them,” says Jamie E. Wright of the Wright Law Firm in Los Angeles. Wright says there’s a widely held belief that plaintiffs receive only a small portion of the settlement while attorneys take millions of dollars in contingency fees. “Lastly, the opposition points out that the right to arbitration has been federally protected as a means of resolution since 1925,” she says.

Arbitration also is popular with employers because studies show that plaintiffs are less likely to win. According to the AAJ, the five-year average win rate of American consumers forced into arbitration who received a monetary award is 5.3%. And it’s getting even worse. In 2020 (the latest year with available data), only 577 Americans in forced arbitration won a monetary award, which is a win rate of only 4.1%. “More people climb Mount Everest in a year (and they have a better success rate) than win their consumer arbitration case,” the report notes.

That’s not to say there are no benefits for plaintiffs. Jessica Glatzer Mason at Foley & Lardner in Houston believes some claimants would continue to choose arbitration even if it were no longer mandatory. And this is particularly true in nonconsumer issues.

“I believe they may prefer to proceed in a confidential forum on these personal claims, in addition to it often being more streamlined and quicker,” she says.

On the other hand, Wayne Cohen, a partner at Cohen & Cohen Attorneys in the Washington, D.C., area, says that while arbitration can help both individuals and corporations, when it’s mandatory and the bargaining power is uneven, there’s an opportunity for abuse.

“Mandatory arbitration always favors those in power—meaning corporate America—over the individual,” Cohen says. “Matters are no longer tried to a jury of one’s peers, but rather in general to an arbitrator who likely does not have the same lived experience in terms of socioeconomic background.”

And he says an arbitrator may reach a very different conclusion than a jury would. “Mandatory arbitration clauses typically extinguish any appellate rights; this means that there is no oversight for a rogue arbitrator.”

That’s not to say that arbitration is perfect for employers. As the use of arbitration has grown, its cost for employers has increased, says Will Manuel, a Jackson, Mississippi-based partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings. “Whereas discovery used to be relatively limited, some businesses are seeing larger and larger bills from lawyers who feel that they need a good bit of discovery to defend the case,” he says. The lack of an appeal process also makes employers uncomfortable, Manuel says. Too big to fail? Another roadblock is that over the last decade, arbitration has become heavily entrenched as a means of resolving disputes.

“The matter is too important to many businesses, both big and small—a constituency that crosses party lines,” Mason says. “The value of the class action waiver, confidentiality and finality to businesses—a benefit available only in arbitration—is likely to be protected by the business lobby.”

Also, there may not be the same level of energy to pass the FAIR Act. “The momentum behind the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment Act of 2021 was fueled largely by some high-profile sexual harassment cases that were covered by arbitration agreements and were ‘quietly’ resolved,” Manuel says. But without that level of press or pressure, he doesn’t think there will be a public outcry to change the arbitration system.

Additionally, the U.S. Supreme Court has taken an expansive view of mandatory arbitration clauses ever since upholding their validity in AT&T v. Concepcion in 2011.

In June, the court actually went the other way in the case of Southwest Airlines Co. v. Saxon and ruled in favor of a Southwest baggage handler, saying she was exempt from a mandatory arbitration clause because she was engaged in interstate commerce.

According to Ben Noren, associate chair of Davidoff Hutcher & Citron’s labor and employment law practice and based in New York City, Saxon was decided on very narrow grounds and was consistent with the Supreme Court’s overall jurisprudence exempting workers frequently engaged in foreign or interstate commerce from the Federal Arbitration Act.

“The Saxon holding does not impact the court’s prior decision in Epic Systems v. Lewis [2018], which upheld employers’ ability to force employees to enter into arbitration agreements and class action waivers,” he says. “There is no indication that the Supreme Court will be going back on its decisions that recognize the right of parties to use mandatory arbitration clauses.”

This story was originally published in the October/November 2022 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Dispute Resolved?: A new law ended mandatory arbitration in workplace sex assault and harassment complaints. Is a wider ban next?”