A trusts and estates lawyer unearths his family’s past

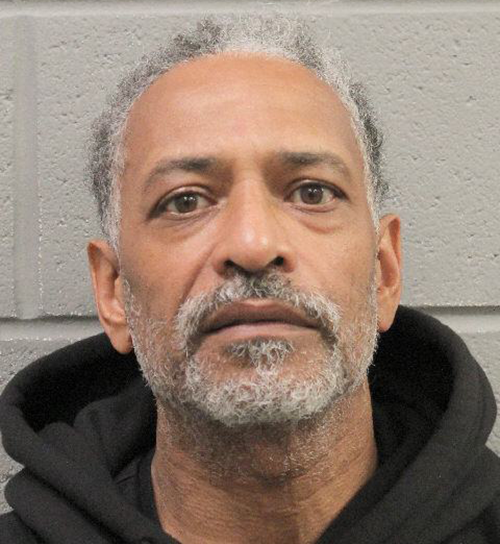

Terrence Franklin discovered documents that revealed his family’s history. Photo courtesy of Sacks Glazier Franklin & Lodise and Terrence Franklin

Character Witness explores legal and societal issues through the first-person lens of attorneys in the trenches who are, inter alia, on a mission to defend liberty and pursue justice.

The story of my family’s emancipation from slavery nearly two decades before the end of the Civil War has shaped my life’s mission and career as a trusts and estates litigator.

I’d been practicing law for nearly a quarter century when I came across a will contest that pitted two brothers against each other, ultimately freed my fourth great-grandmother and set me on a path to pursue justice. My journey of discovery likely would never have happened if I had not become a lawyer—and specifically, a trusts and estates litigator.

A reunion for the history books

In February 2014, my great aunt Viola, who was like a mother to her nieces and nephews, was turning 100. Preparing for a minireunion and surprise birthday celebration for Aunt Viola, I tried to think of how to honor her. Back in 2001, I attended our family reunion and saw among the reunion materials a page of text typed in a cursive font. The text was an excerpt from John Sutton’s will that had been filed in southern Illinois in December 1846. Sutton was a white farmer in Florida and my fourth great-grandfather. He owned my fourth great-grandmother, whom John described in his last will and testament as his “mulatto slave Lucy, aged about 45.” The will went on to state that John also owned Lucy’s eight children and six grandchildren, all listed by name and age. The will called for Lucy and all the children to be freed and removed to a free state, their exodus financed by the sale of all other property.

According to the excerpt, William Adams had performed his duty as executor, delivering Lucy and her family to Illinois, where Adams proclaimed them “free to enjoy their full and perfect freedom.” The excerpt also indicated that copies of the will had been recorded in Florida, where John had made his “X” on the will, and also in Georgia, where the family had lived before moving to Jacksonville.

When I had first returned to Los Angeles from the 2001 reunion, I had sent $2 to a clerk in Jacksonville for a copy of the will. The copy never came, and I forgot all about it.

In 2014, I thought about the will again, and my background in trust and estates proved invaluable. In 2001, I became the first African American fellow in the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel, an invitation-only association that promotes the development of trust and estate law. The week before Aunt Viola’s birthday celebration, I called two Jacksonville lawyers in the ACTEC directory, leaving each a message that I was trying to locate a will from 1846.

The first response was from a lawyer who told me the Great Fire of 1901 in Jacksonville had destroyed most court records. The second was from a paralegal who was intrigued by my quest. She agreed that the Great Fire had destroyed most records but said: “Let me see what I can do.”

That Friday morning, I found an email from the paralegal that said, “We found it! It’s the right will.”

Elated, I asked her to send me a photo. Instantly, I received an image of a broken red wax seal on an old yellowed page with faded ink, written by a lawyer and marked by John Sutton with his “X.” John did not identify any other wife or children, and I surmised that Lucy and John had lived as man and wife, and that Lucy’s children were John’s children.

The mystery deepens, the journey begins

After discovering the will, I wrote an article for Probate and Property magazine wondering if there was love in John and Lucy’s relationship. A professor who read the article emailed me about a book she’d written called Fathers of Conscience: Mixed-Race Inheritance in the Antebellum South.

She followed legal cases where white men left gifts of emancipation to African American enslaved people. Often, white relatives of those men would challenge the wills. Sometimes, the trial courts would uphold the wills. Other times, some courts of appeal acknowledged that the testator had intended to emancipate but held that public policy prohibited emancipation of African Americans.

After learning of such will contests, I felt encouraged to keep digging—that there was more to the story. I also began to outline a novel.

Though I had no reason to suspect that anyone had contested John’s will, I included a contest in the outline for my novel. I “invented” a brother for John, whom I called “Eustice.” I titled the book The Last Will of Lucy Sutton.

When I discovered that ACTEC would have its annual meeting in Florida, my partner, Jeffrey, and I decided to travel to Jacksonville to see the will for ourselves. We drove 5½ hours from the conference in Marco Island to Jacksonville, committing to counting the lynchings documented by Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative in the counties we’d be driving through. We counted 125.

When we arrived in the basement of the Jacksonville courthouse, I was handed a file the size of a lady’s clutch purse, and Jeffrey videotaped me as I took the band off the file and removed four dozen folded pages—the probate file of John Sutton.

The first thing I saw was that red wax seal that I had first seen in the image from the paralegal. I picked up the two-page will. I put my finger on the “X” that John Sutton had made, as I came to understand that I had been on this journey since before I stumbled into a career in trusts and estates, way back to when I’d been a little kid. I begged my dad to buy me a set of calligraphy pens and ink, and a wax letter sealing set. I thought it would be cool to seal letters with red hot wax.

But I was confused: What were the four dozen pages besides the will?

I realized there was a petition to invalidate the will—a will contest! Just as I had imagined, John Sutton had a brother who claimed that John lacked capacity, had been unduly influenced and been plied with “ardent spirits” (alcohol), and that the laws of Florida prohibited emancipation. The only difference was the old-timey name Eustice that I had made up was really Shadrack, right from the Old Testament!

The file included the will contest trial transcript—the handwritten notes of the judge, William F. Crabtree, who transcribed the testimony of lawyer Gregory Yale, who stated that he came to the house because John was too ill to come into town, that Yale was welcomed by John’s “family” not his “slaves,” who also explained to Yale that the family had moved to Florida from Georgia, because John thought he could emancipate them there.

The transcript revealed that Lucy had come in and said she would have been happy to stay in Florida, but Shadrack had threatened to beat her family if he ever came to own them. Lucy’s own testimony would likely have been excluded since she was a mixed-race woman challenging a white man. But Yale could testify, and he summed Lucy up as a “wise old negro.”

The file included a final decree issued by Judge Crabtree on March 10, 1847, upholding the will and ordering Shadrack to pay $28.08 in court costs!

Since discovering the will, I have shared my story with trusts and estates lawyers across the country. When I end my talks, I reference a notion that I first heard paraphrased by my fellow Harvard Law School alum Barack Obama, attributable to a Unitarian minister and abolitionist in a sermon from 1853: “The moral arc of the universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

As I end my talks, I say that I used to think history was what happened to famous people or to ordinary people who did extraordinary things. But my journey revealed that we are all living in the midst of history every day. My ancestors did what they could to guarantee freedom and safe passage for their children. I stand on the same arc of history with them. At the other end of that arc are my descendants who have yet to be born. They’ll call me to account, to answer: “What am I doing, day-to-day, to help bend the arc of history toward justice?”

To help bend the arc, I share the story of my ancestors as a complement to my trusts and estates litigation practice. I encourage underrepresented groups to consider trusts and estates, and in my spare time I work on various creative projects to share the story of John and Lucy Sutton.

This article first appeared in the September-October 2019 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline “Law Imitates Life: A trusts and estates lawyer unearths his family’s past.”

Terrence Franklin is a partner in the Los Angeles trusts and estates litigation firm of Sacks Glazier Franklin & Lodise who serves as the chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee of the American College of Trust and Estate Counsel. He was recently included among the Most Influential Minority Attorneys in Los Angeles by the Los Angeles Business Journal.