4 lessons we can learn as a profession from the pandemic

Photo illustration by Brenan Sharp/ABA Journal.

In the seventh week of the pandemic lockdown, I went on a solo walk in the rain. A soggy pile of books on a Brooklyn sidewalk caught my eye. One lay open to a page with the title “Object Lesson.” When I got home, I looked up the meaning of the phrase:

• “A striking practical example of a principle or an ideal.”

• “A concrete illustration of a moral.”

• An action, situation or event that demonstrates a truth.

It got me thinking: What are some lessons of this COVID-19 experience for the legal profession? What are some truths that are coming to light? Four initial lessons come to mind.

Lesson No. 1: Our definition of talent needs to expand

Legal employers and legal educators who hope to wait this out and then go back to business as usual are fooling themselves. Things are never going to be the same as they were. The institutions that will survive—and thrive—will reject outdated hierarchies and systems that continually attract and promote the same people. Sustainable entities will seek out and champion nontraditional talents and skills.

Past interviews for law jobs focused on GPAs, traditional law school accolades and applicants’ gift of gab. Once hired, those employees who excelled at office face time and racked up maximum billable hours won plaudits from performance evaluators. It’s time to let go of systems, hierarchies and performance metrics that do not serve the profession or society. Instead, we must consider and invest in previously undervalued and overlooked individual and collective strengths.

In both the immediate and distant future, the successful legal employers will be those who appreciate how different individuals flourish in traditional and nontraditional working environments. Lockdown has pulled back the curtain, revealing that many members of our legal communities, with the right support, can excel in work-from-home scenarios—even if they are working at odd hours while sharing space with and caring for others. Instead of hankering to pull everyone back to the brick-and-mortar office, let’s reconsider what it means for an employee to be “productive” or “contributing.”

A first step is to restructure the way we interview and draw out strengths such as:

• An ability to focus and produce high-quality and timely work, independently and unsupervised.

• Excellent oral and written communication skills in virtual spaces.

• Openness to and facility with adjusting to new technology.

• Creativity in designing solutions to complex problems—in law and other disciplines and industries.

• Collaborative problem-solving capability—also across other disciplines and industries.

We also must more highly appraise job applicants and employees with emotional intelligence, such as those who can exhibit empathy toward and authentically reassure clients (and co-workers) navigating unparalleled emotional, financial or other trauma.

Lesson No. 2: Our communication skills are overdue for an upgrade

Our profession hinges upon effective communication, but often we fail to model productive dialogue. Let’s seize this opportunity to improve how we converse in person and in virtual spaces.

In New York’s daily pandemic press briefings, the clamor of reporters seeking to ask Gov. Andrew Cuomo a question prompted him to suggest, that instead of yelling at each other, how about the journalists go one at a time to make sure everyone gets a chance to ask a question? I have wondered—for 26 years—why we don’t conduct lawyering activities such as depositions, negotiations and oral arguments in a less disruptive fashion, rather than the usual riot of interruptions in which the loudest voices often reign. The governor’s commonsense suggestion could apply to lawyering scenarios as well.

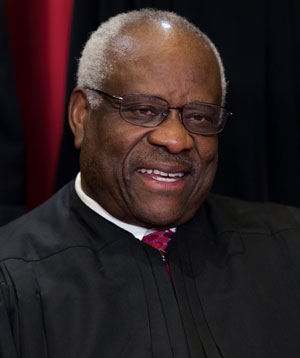

Photo of Clarence Thomas by SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images.

The U.S. Supreme Court already presented a prime example of such a communications upgrade. In October, the court started allowing advocates to have two minutes to present initial statements without interruption; and mid-pandemic, it announced a new protocol for its first-ever telephonic arguments: The justices would ask questions in order of seniority rather than the usual free-for-all. Some folks on Twitter and cable news seemed surprised that Justice Clarence Thomas—traditionally quiet in oral arguments—unmuted his microphone, actively questioning advocates in the court’s new format of telephonic hearings. When I started hearing the buzz about Thomas’ invigoration in this new platform, I immediately thought, “He must be an introvert.” Introverts resist interruption. Thomas made an appearance at the University of Kentucky in 2012 at which he discussed his views on the traditional format of justices interrupting advocates with questions. He remarked, “Maybe it’s the introvert in me, I don’t know. I think that when somebody’s talking, somebody ought to listen.” It makes sense why he would speak up more readily now, without the expectation to speak over an advocate or a colleague to be heard.

Lesson No. 3: To amplify unheard voices, we must change how we engage

Making the quick switch to “emergency remote law teaching” in March, some educators indicated they planned to merely shift their in-person teaching style onto the online platform and continue cold-calling students, but now on video. As a researcher of how traditional models of legal education already underserve introverted, naturally quiet and shy students, I yearn for this crisis to inspire an evolution in legal education. As an introvert who resists being put on the spot and interrupting others to be heard, I rejoiced at discovering Zoom features such as “chat” and virtual hand-raising. I was excited to see how quieter law students might amplify their voices in online spaces.

In the past few months, experts at multiple levels of education have reported anecdotally that many quiet students are engaging more readily in remote learning. In a CNN interview, Sundai Riggins, an elementary school principal in Washington, D.C., relayed how students who were not talkative in regular in-person classes were expressing themselves much more frequently in distance learning. In an Edutopia article, a high school psychology teacher in Alabama, Blake Harvard, said “the online environment may allow for voices to be heard without the added bit of social anxiety.” Barbara Gartner, an English-as-a-second-language specialist at Brooklyn Law School, told me one international student felt more empowered in the Zoom classroom than in “the big lecture hall.” The student shared that she could hear and understand the professor better, and she “felt freer to ask questions.”

Instead of trying to cling to “business as usual” in these unusual times, let’s experiment with a broader range of techniques, activating more platforms to engage all voices.

Lesson No. 4: Serious well-being initiatives are as essential as oxygen

Before the pandemic, our profession made strides to address our well-being crisis. Now, it’s even more clear that a conversation about and a strategic plan to address the mental, physical and emotional health of all members of our legal communities, including our administrative support teams, is essential.

Continuing to shelter at home, striving to be productive and keep businesses going, many employees and colleagues also wrestled with trauma, fear, anxiety, loss, pain, depression and grief.

The events of 2020 are converging into one of the biggest traumas we—as individuals, a country and a global community—will face in our lives. Some of us who thought we had worked through past injuries such as divorce, loss of a loved one or 9/11 are discovering that solo isolation is triggering unresolved grief. Saying this out loud does not make us weak; processing it together builds collective fortitude.

The legal institutions that give serious thought to this reality and go all in on building infrastructures to support the mental, physical and emotional health of every member of their communities will rise up, impenetrable. Those who don’t will collapse. They will lose their beating heart. We need heart now more than ever.

Overall, let’s pause and assess the lessons we can learn from 2020. Let’s be and do better.

This story was originally published in the August-September 2020 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Pandemic Pause: Some lessons we can learn as a profession.”

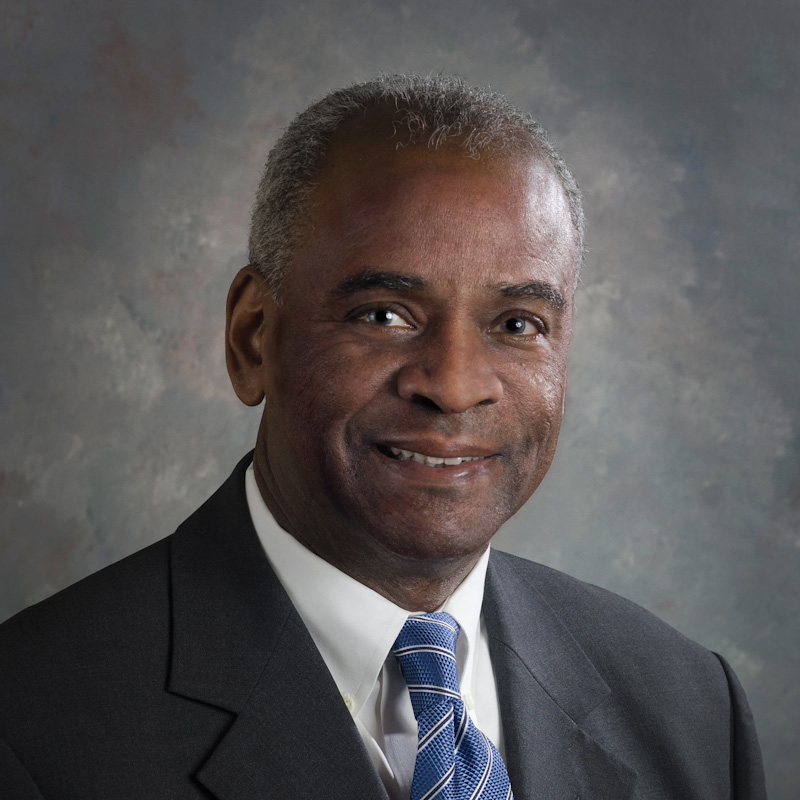

Heidi K. Brown is an associate professor of law and director of legal writing at Brooklyn Law School. She is the author of The Introverted Lawyer: A Seven-Step Journey Toward Authentically Empowered Advocacy (ABA 2017) and Untangling Fear in Lawyering: A Four-Step Journey Toward Powerful Advocacy (ABA 2019).