How one lawyer is trying to solve a John Wayne Gacy murder mystery

Becker walks toward the plot where “body No. 14” is buried. The lllinois native can recall the terrifying news of the Gacy murders unfolding when he was a teenager. Photo by Wayne Slezak/ABA Journal.

Steven Becker wasn’t sure what he’d see at his first exhumation. He’d been a criminal defense lawyer for more than a decade. He was used to filing Freedom of Information Act requests and litigating civil rights matters, not watching coffins emerge from the earth. But here he was, on Sept. 5, 2012, at the Queen of Heaven Cemetery in Hillside, Illinois, on behalf of his client, who insisted that the body in the coffin was not—despite what police said—her son.

It was early in the morning. It was cloudy and quiet. Becker hadn’t notified the media; he wanted it to be a reverent process. A crane lifted the burial vault from the grave, and two workers guided it onto the back of a flatbed truck and brought it into a nearby building. They took out the coffin and opened it up. The pathologist began to go through the remains. Before long, he lifted out a clear plastic bag containing the skull, and Becker was shocked to see that the entire lower half of it was missing. The jaws were gone. And the jaws were very important.

The road that led Becker to this particular gravesite started in fall 1976, when a teenage Chicagoan named Michael Marino told his mother that he was heading out to see his friend Kenneth Parker. Neither boy ever came home. For the next two years, the police told Sherry Marino that her 14-year-old son had run away, even though she insisted he’d never do something like that. And then suddenly, the city filled with talk of a serial killer.

On Dec. 21, 1978, police arrested John Wayne Gacy, a jovial suburbanite who was involved in local politics, dressed up as a clown for children’s parties and had been burying young men and boys under his house for years. The Cook County medical examiner dropped down into Gacy’s soon-to be-infamous crawlspace wearing coveralls, saw a pair of human arm bones sticking up from the ground and ordered the entire house sealed.

Becker was a teenager at the time of Gacy’s arrest, living 40 miles south of Chicago on a farm with his parents and two younger brothers. He remembers the “horror of it,” and he was roughly the same age as the victims, but school and farm work kept him distracted. (His specialty was raising bees.) Across the area, though, anyone with a missing boy shuddered.

The Chicago Police Department put out a request asking families with missing sons who fit the profile of a Gacy victim to send in their sons’ dental records. The medical examiner had been pleased to find that most of the bodies in the crawlspace still had their jawbones; teeth were vital when it came to identifying victims in the pre-DNA world of 1978. Marino submitted Michael’s records, which noted that one of his upper molars was missing. But before long, police were assuring Marino that her son was not among the 33 dead.

And then they changed their story. On March 12, 1980, Gacy was found guilty of 33 counts of murder. Immediately after the trial, the police knocked on Marino’s door. “We made a grave error, Mrs. Marino,” her daughter Melissa remembers them saying. “Your son was a victim.”

A 1978 police photo of John Wayne Gacy, taken when he was held for questioning in connection with the discovery of decomposed bodies in the crawlspace of his home. Gacy operated a construction business from the residence and employed several young men and boys, according to neighbors. Gacy covers his face as he is led to a courtroom where he was charged on Dec. 22, 1978, with slaying a teenage boy. Photos by Bettmann/Contributor via Getty Images; AP Photo

Gacy’s victims had been labeled in the order they were removed from the crawlspace, and police told Marino that body No. 14 was actually her son. Suddenly, Marino was a member of Chicago’s most grief-stricken club: the family members of Gacy’s victims. She joined their ranks, ready to fight for justice. She won a wrongful death suit preventing Gacy from profiting from any book or movie deals. In 1994, she waited on the grounds of the Stateville Correctional Center as Gacy was executed, telling the press, “My son should be mentioned. I am here for Michael Marino, who was 14 years old. My son should be mentioned.”

Still, Marino had her doubts. She thought it was strange that her son was declared a Gacy victim only after the trial was over, after the police had held on to his dental records for more than a year. The clothing that had been found with body No. 14 wasn’t what Michael had been wearing when he said goodbye to her. And she didn’t trust the police. There had been too many moments when she felt as if they were lying to her, first telling her that they’d seen her son around the city and now telling her he’d been dead the entire time. She just didn’t believe them. Every day, rain or shine, she walked the streets of Chicago and the surrounding suburbs looking for Michael.

“I’ve gone all over,” she recalls. “Places I’ve never heard of, streets I’ve never heard of.” She’d follow the most outlandish of tips down the city’s most obscure streets, and she’d elbow her way into dangerous drug dens, just in case somebody really knew something.

“I believe that God gave me certain angels, because I should be dead a hundred times over,” she says. “I would talk to people that most people wouldn’t talk to, and I had a pretty big mouth.”

Body No. 14 was buried on April 12, 1980, in the Queen of Heaven Cemetery under a gravestone that reads: “Beloved Son: Michael M. Marino.” She’d visit the grave religiously. But every time she was there, the ground felt cold. She’d say, “Michael, if this is you, please give me a sign.” Nothing. Just the cold. She needed a lawyer.

The lawyer and Mrs. Marino

Lawyer Steven Becker never could have expected a client like Marino to show up at his office. But when his private detective brought Marino into his office, explaining that she wanted to look further into the death of her son, Becker found the dark-haired mother a persuasive figure.

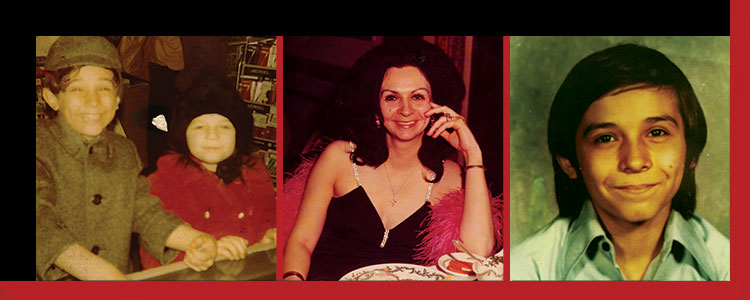

Sherry Marino (center) in happier times, just months before her son went missing. Michael Marino was 14 when he disappeared in October 1976. On the left, Michael shares a laugh with his sister Melissa. Photos courtesy of Steven Becker.

“Mrs. Marino was very demure, she was soft-spoken, but she was very convinced that her son was not a Gacy victim,” he says. “At that point, I wasn’t sure what was going to happen, but I just figured at least I could try to bring some closure to her.”

Becker had just left his job at the Office of the State Appellate Defender—where he represented indigent prisoners on appeal—in order to start his own private practice. Marino was one of his first cases. He took her on pro bono.

By the time Marino met Becker in 2011, she had been trying for 35 years to get someone to listen to her. Most people thought, frankly, that she was crazy.

She put up reward posters around the city and followed every lead, all of which turned out to be fake. “I went for it every damn time,” she says. “They would say, ‘Meet me at so-and-so,’ and I couldn’t get there quick enough.”

She gave out so much money, in fact, that it affects her to this day. “After you hand out money for 40 years, you have very little left,” she says.

When she wasn’t out in the streets searching, she sat in the waiting rooms of Gacy’s prosecutors and watched them walk right past her. She haunted the police. Melissa, her youngest child, remembers accompanying her mother to the Youth Investigation Division of the Chicago Police Department and watching her grow so upset at the cops that she’d lunge for them. Melissa would pull her mother back, terrified that she’d “get her brains splattered all over the police station.”

Anytime anyone remotely connected to the Gacy case appeared on TV—which happened less and less over the years—Marino would write down their names and call them. At the end of 2010, a former homicide detective named Bill Dorsch appeared on local station WGN-TV.

Dorsch had his own problems with the Gacy case. He had long suspected that Gacy had buried bodies elsewhere, particularly at a Chicago apartment building where Gacy had been the caretaker. Dorsch lived around the corner in 1975 when he spotted Gacy outside at 3 a.m. with a shovel in his hand. “You know me,” the killer said. “Not enough hours in the day. You’ve got to get it done.”

When Marino saw Dorsch on TV, talking about how he wasn’t satisfied with the cops’ 1998 excavation of the building in question, she screamed to her nephew, “Come here and write this stuff down! I wanna call this guy.” They met up. At the time, Marino had been trying to get the autopsy report for body No. 14, but she hadn’t been able to navigate the system herself.

Left: The dig site outside the Gacy home in suburban Chicago, where the remains of 29 of his victims were found between December 1978 and March 1979. The house was demolished shortly thereafter. Right: An unsuccessful 1998 attempt—four years after Gacy’s execution—was made to find the bodies of more of the serial killer’s possible victims at the apartment building where his mother had once lived and he’d been the caretaker. Grid patterns on the building’s lawn mark the spots where the excavating was to begin. Photos by Jay Crihfield/AFP via Getty Images; AP Photo/Charles Bennett; AP Photo/CEK

So Dorsch took her to the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office. The medical examiner, who knew Dorsch from his days as a Chicago homicide detective, told him, “Bill, leave this one alone.” Dorsch found this ominous. So he decided to introduce Marino to Becker, for whom he was working as a private detective.

Becker was experienced with filing FOIA requests, which Marino needed to access the autopsy report. In fact, his first case out of law school was an FOIA suit on behalf of his professor, M. Cherif Bassiouni, who was known as the “father of international criminal law.” Bassiouni, a professor at DePaul Law School, was openly pro-Palestine, which got him flagged by the CIA and the FBI—unconstitutionally, Becker thought. So he sued the CIA, as well as the FBI, for their files on Bassiouni.

After that, Becker went on to handle other complex matters, including representing alleged drug cartel members in international extradition cases and a Bosnian minister of foreign affairs who was convicted of crimes against humanity.

With experience like that under his belt, Becker figured he could help Marino access the autopsy report without much trouble.

“I had never dealt with a serial murder case before, never intended to be involved in one, but this was an area I knew well,” he says. Becker was successful in his request and received the autopsy report, which came with a series of gruesome photos that he refused to show Marino. He never could have predicted the “10-year odyssey,” as he calls it, that came next.

The evidence wasn’t matching up

Once Becker received the autopsy report for body No. 14, he began scrutinizing the report against Michael Marino’s dental records—and Sherry Marino’s memory. There were inconsistencies.

Body No. 14 had a “possible healed fracture of the right clavicle,” but Michael had never broken his collarbone.

The report declared that body No. 14 was white “with some slight to moderate Mongoloid (probably American Indian) admixture,” but Michael was 100% Italian.

Most important, the jawbones of body No. 14 showed no “antemortem tooth loss.” In other words, when this young man was killed by Gacy, all of his teeth were intact. Michael, on the other hand, did have a missing tooth. Seven months before he vanished, he had an upper molar removed because of a bad cavity. His mother had taken him to the dental appointment.

Armed with these inconsistencies, Becker filed a petition for exhumation. This was a rare move for a private attorney, but the judge declared that he could proceed, though he would have to raise the funds himself. Marino immediately gave as much money as she could, and donors provided the rest.

After raising upwards of $6,000—and getting a discount from the Archdiocese of Chicago—the exhumation took place in fall 2012. Becker watched the pathologist take out a saw and carefully remove little pieces of bone. Since the jaws were missing, the pathologist had to take the DNA from elsewhere on the skeleton. They sent the bone fragments to an established medical laboratory chain called Labcorp, and Marino sent in her DNA separately. Anticipating pushback from the authorities, Becker made sure everything was documented by film or photograph.

Photo of Michael Marino’s grave. Photos by Wayne Slezak/ABA Journal

The judge who granted Becker’s petition for exhumation had also declared that a representative from the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office could attend the exhumation and collect their own DNA. But no one ever showed up. Instead, Becker received two letters from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office asking to be informed of the DNA test results before the media.

“It was very clear the sheriff’s office was simply interested in controlling the narrative, I think possibly anticipating that there could be a misidentification,” Becker says. He refused to give them the results in advance.

Thirty-six years to the day that Michael Marino went missing, the results came back from Labcorp. Becker solemnly informed his client that she’d been right all along: Body No. 14 was not her biological son.

“She didn’t break down, she wasn’t crying,” Becker says. She just sat there and said over and over again, “I knew it.”

Who was buried in Michael’s grave?

So where was Michael Marino? And who was in his grave? In an attempt to find an answer for his client, Becker found nothing but questions. Although he provided the Cook County Sheriff’s Office with portions of the DNA results—“five different loci of the chromosome of the DNA, which is basically a very definitive nonmatch”—they refused to acknowledge them.

The orthodontist who originally worked on the case told the Chicago Tribune that he’d “stake [his] wife and children” on the fact that “the body and the X-rays given to me as Marino are one and the same.” The sheriff’s office declared that they wanted to do their own exhumation and their own DNA testing. They wanted access to Sherry Marino’s full DNA profile, and they wanted to interrogate both her and her daughter.

Authorities dug up a paupers’ grave in 2011 in search of missing jawbones from the serial killer’s victims. Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart speaks at a fall 2011 press conference in Chicago about the renewed effort of his office to determine the identities of eight unidentified Gacy victims. Photos by AP Photo/Paul Beaty; AP Photo/Cook County Sheriff’s Department

“That’s where we hit loggerheads,” Becker says. Marino was unwilling to hand over her DNA and had no interest in being interrogated as though she were guilty of something.

“She really was horrified,” he says. “She simply did not trust law enforcement.”

So Becker kept working, pressing at the weird spots in the Gacy case like he was poking at a bruise. “From the exhumation until at least 2016, I likely spent more time on Michael’s case than on any other,” he says. “The collective hours over the last decade are incalculable.”

He wasn’t doing it for money—the work remains pro bono to this day—but the case had gotten its hooks in him. “It’s of course been an extremely interesting case,” he says. “It’s been intellectually challenging as well.”

Marino felt strongly that she had been repeatedly wronged by the system—and, as a defense lawyer, the idea of systemic corruption really riled Becker.

But his connection to the case wasn’t just intellectual or moral. His older brother had been born with an inoperable heart condition and passed away the age of 2½. Becker knew well how much that had affected his mother. He was no stranger to the sight of a mother grieving for her son.

He requested another exhumation, this time for body No. 15, thought to be Michael’s friend, Kenneth Parker. Bodies 14 and 15 were found buried together, with No. 14 on top of No. 15, and Becker thought perhaps the remains had accidentally been switched. But body No. 15 wasn’t Michael, either.

He learned that the missing jawbones of body No. 14 were stashed in plastic buckets in a paupers’ grave, along with the jaws of all the other Gacy victims. After the trial, these jaws sat in the “bone room” at the medical examiner’s office until 2009, when they were ingloriously buried.

Becker was informed by the Office of the President of the Cook County Board of Commissioners that an administrator at the medical examiner’s office had performed an “extensive search” and was unable to find any paper trail “pertaining to the decision to retain the mandible and maxilla bones of John Wayne Gacy’s victims” or to “the decision to bury or to the burial itself.”

“Absolutely incredible,” Becker says. “In the most prolific serial case at the time!”

Given that there are still six official unidentified Gacy victims (seven, if counting body No. 14), why wouldn’t authorities hold on to at least those jaws, each one a rich source of DNA? And as far as why the jaws of the known victims weren’t returned to their families after the trial—a move that was actually illegal under Illinois law at the time—“it raises questions as to whether they had questions about the accuracy of the identification of [those] victims,” Becker says.

Digging for clues deepens the mystery

The Gacy case is full of moments like this. Are the jaws part of a conspiracy of silence, pointing toward a larger darkness at the heart of the case? Or did some poor intern accidentally throw away the paperwork? It’s these strange moments that have drawn others to the mystery.

The case has turned into something of a rabbit hole; get close enough, and you’ll go tumbling down. There, you’ll meet scrappy characters such as former Chicago Reader editor Alison True and filmmaker Tracy Ullman, who were pulled in by Bill Dorsch and who have been working on long-form projects about the case for 10 years.

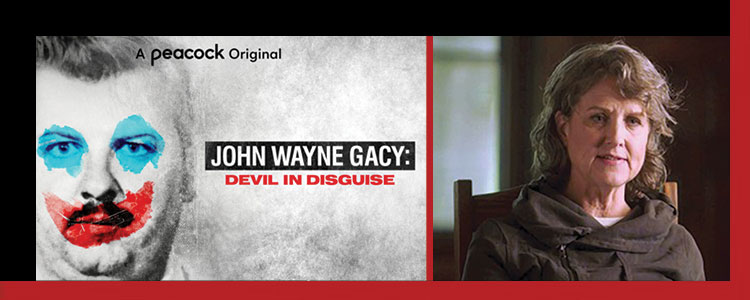

True and Ullman are the executive consultant and executive producer, respectively, of a recent six-part documentary on NBC’s Peacock streaming platform titled John Wayne Gacy: Devil in Disguise, which argues that the Gacy case is rotten at the core due to Gacy’s political connections (he was a precinct captain who infamously took a photo with first lady Rosalynn Carter) and his link to organized crimes (such as a sex trafficking ring that operated out of Chicago called the Delta Project).

These theories stretch far beyond Marino’s personal search for the truth, but the struggles she’s had with her case may point to a deeper corruption.

“Because of the sheriff’s ongoing responses to Becker, my sense that the original case is problematic is just reaffirmed,” True says.

The ABA Journal made several attempts to interview an official with the Cook County Sheriff’s Office, which stopped responding to emails. (Editor’s note: After publication, the Sheriff’s Office responded with a statement, as did Becker.)

Of course, Marino and her daughter Melissa are there, down the rabbit hole, and have been for decades. They see treachery everywhere they turn; they are overflowing with stories of odd behavior and sinister events.

Alison True is an executive consultant for John Wayne Gacy: Devil in Disguise, the recent six-part documentary on NBC’s Peacock streaming platform. Photos by AP Photo/Chicago Sun Times; Peacock

For example: After Michael disappeared, they started receiving magazines such as Newsweek and Amusement Business—a now-defunct publication about theme parks—addressed to Michael Marino. Six weeks after he vanished, someone broke into their apartment, slashed up his clothing and stole all of Michael’s recent photos. What did it all mean? Nothing? Everything?

When Marino began searching for Michael, she’d write all her findings down in a code she invented herself, paranoid that others would find her notes and abuse them somehow. It sounded outrageous. But so had her story about Michael’s grave feeling “cold,” and look at how that turned out.

After the DNA results, one of Marino’s neighbors told her daughter, “Man, we just thought your mom was losing it. Man, turns out that she was right.”

A few years ago, Becker finally got a bit of validation for his work. Marino had been going through her files and found an old letter from former U.S. Sen. Charles Percy from Illinois, whose own daughter was murdered in 1966—a case that remains unsolved. Back in 1980, she’d called Percy’s office, expressing her doubts about the identification of body No. 14. And Percy wrote back to her.

He said he’d spoken to Gacy’s lead prosecutor, who explained that “despite some initial uncertainty due to a discrepancy in dental charts, one of the bodies recovered from John Gacy’s home has been positively identified as that of your son.”

Becker homed in on that word: discrepancy. He’d never heard this admitted before. “This is the first documentary proof I got, years later, that there was a problem,” he says.

‘That wicked wind whispering around you’

Marino refuses to say “John Wayne Gacy.” She simply calls him the devil. After Michael disappeared, Melissa watched the life drain from her beautiful mother’s eyes. “It’s actually, like, killed my mom,” says Melissa. “I’ve seen it just wither right out of her, her life.”

Marino’s hopes rose after the exhumation. Local news sources—and a few national ones—reported on it. The Wikipedia page for John Wayne Gacy was dutifully updated. But then—nothing. The medical examiner’s certificate of death for body No. 14 still bears the name “Michael Marino” and lists the date of his death as Dec. 27, 1978. There was no huge reckoning with the Gacy narrative, no call to action. Instead, everything fell silent again.

Part of the silence was intentional: The Gacy case was open again, which meant that the public no longer had as much access to it as they used to. It had been open since 2011, actually, right around the time the judge granted Becker’s petition for exhumation.

Days after the ruling, Sheriff Tom Dart and his team exhumed the eight bodies of Gacy’s officially unidentified victims. Two would eventually be identified, to great acclaim.

True, who’s working on a book about Gacy, finds this move “interesting from a legal standpoint,” because the fact that the case has been reopened “gives them ground to refuse FOIAs. Not only do they get to sit on all the information, they don’t really have to do anything. That’s the answer they give any request.”

True—and others interviewed for this article—knows that her stance can sound paranoid.

“I’ve had to fight my natural skepticism and consider that there is a conspiracy of silence around the Gacy case,” she says.

Melissa Marino puts it more colorfully: “You become in such a fog, like that dense London fog, that you can’t see anything. All you can hear is that wicked wind whispering around you. But you can’t see it.”

Today, Becker spends less time on the case than he used to, but he’s still chipping away at it. He’s trying to get Marino’s DNA into the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System, thinking that if Michael Marino is already in the system as a John Doe, his mother’s DNA will match up with his. But since NamUs is a law enforcement database, Becker can’t submit her DNA himself, and law enforcement won’t.

“If [Marino] puts her DNA into the database and it comes back with a positive hit on another unknown decedent across the country, that would show that body 14 definitively is not Michael Marino,” Becker says. “They have a vested interest in making sure her DNA does not get into the database because then they can claim there was no mistake.”

When he’s not working on this case, Becker keeps busy with post-conviction matters and international law, as well as representing his Bosnian war-criminal client. When he’s not doing that, you can find him reading religious texts (he’s Protestant but loves the beauty of Catholic churches and relics), playing piano or composing music.

Though the local cops aren’t too pleased with him these days, it doesn’t bother Becker. He’s gone up against the CIA and the FBI. The Cook County Sheriff’s Office “is not a major opponent, in my view,” he says.

And Marino waits for more news. Sometimes she’ll turn to her daughter and wish aloud that there was more she could do. She has turned over every stone in her power, but she will never be satisfied until Michael is found. She’s lived in her apartment in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, a stone’s throw from Lake Michigan, for 50 years. She refuses to move.

“I always say to myself, ‘If Michael was coming home, he would know exactly where to come,’” she says. “He wouldn’t have to look for me.”

Editor’s note: After the June 1 publication of this article, the Cook County Sheriff’s Press Office responded with the following statement, slightly edited.

The only goal of the Sheriff’s Office is to seek the truth regarding the identification of victims in the Gacy case. For years, Sheriff’s Police detectives have tried to work with Mr. Becker, his former partner Robert Stephenson and Mrs. Marino, but they have refused every single request to cooperate in our investigation.

Over the years, more than a dozen different board-certified forensic odontologists have independently reviewed the dental charts and radiographs of Michael Marino and compared them to the victim No. 14. All have unequivocally concluded that Michael Marino and No. 14 are one and the same person.

The exhumation, collection and testing of the DNA sample that Becker claims is definitive proof that Michael Marino is not No. 14 were not witnessed by the Sheriff’s Office or any other law enforcement agency, contrary to accepted best practices for a forensic investigation. Mr. Becker refused to share information with the Sheriff’s Office and failed to include us in the exhumation. As such, the results of this work cannot be verified for use in a criminal investigation. Further, the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office was never notified by Becker of the exhumation and as a result did not participate—despite the court order Becker obtained which said that they could participate.

At every turn, Mr. Becker has conducted his investigation in secrecy, sharing virtually no information with us and actively refusing to involve Sheriff’s Office or other government agencies with jurisdiction in this case. When Mr. Becker was asked to share the DNA results with our office, he provided a redacted document that was of no value. The Sheriff’s Office remains willing to review the full and unredacted evidence that Becker claims are proof that Michael Marino is not victim No. 14.

The Sheriff’s Office reopened the case to seek the truth about who the unidentified Gacy victims are, not to prevent records from being obtained by FOIA. Ms. True’s statement to the contrary is absurd and lacks any basis in fact. As with any open criminal investigation, records may be withheld while the case is pending, but the Sheriff’s Office has provided hundreds of records related to the Gacy case pursuant to FOIA requests and will continue to do so.

The statement in the article that the Sheriff’s office wished to “interrogate” Mrs. Marino and her daughter could not be further from the truth. The Sheriff’s Office has repeatedly expressed its willingness to meet, talk with and help Mrs. Marino. The mischaracterization of the office’s compassionate outreach as “interrogation” is utterly inaccurate and again, without any basis in fact.

Mrs. Marino’s loss is unbearable and heart-wrenching. Sheriff Dart, a father and former prosecutor, offered to meet her in person and offered all of the office’s assistance. Unfortunately, Mr. Becker and others continue to peddle conspiracy theories which help no one get any closer to the truth of what occurred. Their efforts have exacerbated Mrs. Marino’s pain and suffering.

Matt Walberg

Press Secretary, Cook County Sheriff’s Press Office

The belated press release from the Cook County Sheriff’s Office is replete with factual inaccuracies. My staff and I met with Sheriff Dart and his detectives on multiple occasions, as well as with the cold case unit of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office. We made numerous attempts to come to an amicable arrangement with the Sheriff’s Office to do additional DNA testing, including trying to broker an agreement through an independent third-party organization. Yet the Sheriff’s Office has consistently refused to conduct DNA testing through an independent laboratory.

In addition, the assertion that our investigation into Michael Marino’s case has been conducted in secret is simply not credible. The exhumation petition was filed in the Circuit Court of Cook County, and the judge granted the petition at a public hearing in which the authorities were represented by both the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office and the Illinois Attorney General. Extensive coverage in the Chicago Tribune, as well as other press, easily belies this assertion. Therefore, the Sheriff’s claim that he was somehow unaware of the exhumation is incredulous.

In fact, prior to conducting the exhumation, I was invited to a private meeting with the forensic odontologist who originally identified body No. 14 and a member of Sheriff Dart’s own staff, who, not coincidentally, happened to be one of the original prosecutors on the John Wayne Gacy case. They tried to dissuade me from proceeding to the exhumation on the grounds that it would be too traumatic for my client, Mrs. Marino. It has become clear that the Sheriff’s Office’s concern for Mrs. Marino is nothing more than lip service for public consumption. The Sheriff’s Office has always had the ability to conduct its own exhumation if it were really interested. It just fears what it might find if it digs any deeper.

This story was originally published in the June/July 2021 issue of the ABA Journal under the headline: “Unearthing Justice: How one lawyer is trying to solve a John Wayne Gacy murder mystery.”

Tori Telfer is the New York City-based author of "Lady Killers: Deadly Women Throughout History" and "Confident Women: Swindlers, Grifters, and Shapeshifters of the Feminine Persuasion" as well as the host of the podcast Criminal Broads.