Iraq Is New Front in Detainee Battle

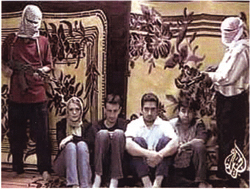

Mohammad Munaf appears above to the right of

three Romanian captives.

The long legal battle over the u.s. prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, has succeeded in raising—but not yet answering—a basic question about American law: What is the reach of habeas corpus? Is the right to take your case before a judge limited to American citizens in the United States? Or does it extend to prisoners around the world when they are arrested and imprisoned by U.S. authorities?

The U.S. Supreme Court is expected to rule this spring for the third time on whether habeas corpus extends to foreign prisoners held at Guantanamo. The justices have twice decided, by narrow margins, that these detainees have habeas rights.

But those decisions have had little impact, in part because Congress has voted twice, also by narrow margins, to revoke the right to habeas corpus for “aliens” who are held as “enemy combatants.” The pending question in Boumediene v. Bush, No. 06-1195, argued in December, is whether the Constitution protects this right for the men imprisoned at Guantanamo, regardless of what Congress says.

This month the legal battle over habeas corpus moves to a new front: Iraq. On March 25, the justices are slated to hear appeals from two naturalized Americans who were arrested by U.S. troops in Baghdad and held there in a military prison. One, Mohammad Munaf, was turned over to the Iraqis and, according to his lawyers, convicted and sentenced to death in a closed 15-minute proceeding. However, he remains in the custody of the U.S military at Camp Cropper near the Baghdad International Airport.

The other prisoner, Shawqi Ahmad Omar, is a dual citizen of Jordan and the United States. In October 2004, U.S. troops raided his home in Baghdad when they were targeting associates of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the former al-Qaida leader in Iraq. Omar was accused of harboring an Iraqi insurgent and four Jordanian jihadist fighters. He, too, is held at Camp Cropper.

The court has combined the cases, Munaf v. Geren, No. 06-1666, and Geren v. Omar, No. 07-394.

Munaf’s and Omar’s lawyers have been active in the Guantanamo litigation. They include Northwestern University law professor Joseph Margulies and Jonathan Hafetz of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University. They are asking the court to rule that U.S. citizens held by the military—in Iraq or anywhere—deserve both the right to have their cases heard by an American judge and a chance to contest the evidence against them.

“These cases test the fundamental principle that U.S. citizens have a right to habeas corpus when they are detained by their own government,” Hafetz says. “If Americans can be transferred and executed without court view, it will contradict the most basic guarantees of our Constitution.”

A MULTINATIONAL TACK

Not surprisingly, the Bush administration’s lawyers argue for a hands-off approach by the courts. Their explanation for this position is surprising, however. They do not rely on the familiar argument that wartime decision-making is entrusted to the president and his military commanders. Instead, they suggest that the U.S. military force in Iraq is not truly an American operation.

Munaf and Omar are held by the Multinational Force-Iraq or “MNF-I,” Solicitor General Paul Clement said in his brief. This is “an internationally authorized entity consisting of forces of approximately 27 nations, including the United States.” These troops operate “pursuant to a United Nations mandate,” and “the multinational force is legally distinct from the United States, has its own insignia and includes high-ranking officers from other nations,” he said.

Beyond that, Clement said, it would be unwise and unwarranted for a U.S. judge to “intrude on Iraq’s sovereign interest in prosecuting serious criminal offenses committed within its own territory.”

To complicate matters further, two panels of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit split on the two cases. In February 2007, one panel, in a 2-1 decision, upheld an order that enjoined the U.S. military from turning Omar over to Iraqi authorities. Judges David Tatel and Harry Edwards said Omar was an American citizen who had been held for more than two years without charges being filed. They agreed a district judge has habeas jurisdiction to hear his claims. Omar v. Harvey, 479 F.3d 1.

In April, however, a different panel, led by Judge David Sentelle, said U.S. judges “do not have the power or authority to entertain Munaf’s petition” because he had been convicted by an Iraqi court. Munaf v. Geren, 482 F.3d 582.

Sentelle relied on a post-World War II decision of the Supreme Court, which refused to interfere in the military trial of several Japanese prisoners. In a per curiam opinion consisting of nine sentences, Hirota v. MacArthur, 338 U.S. 197 (1948), the court demurred because this military tribunal “is not a tribunal of the United States.”

Applying that reasoning, Sentelle said the Iraqi court that sentenced Munaf to die “is not a tribunal of the United States.” This rationale gave no weight to the fact that Munaf is a U.S. citizen, unlike the Japanese prisoners held by Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

MUCH TO SIFT THROUGH

The Supreme Court voted to take both cases to sort out the situation. The facts of Munaf’s case are hard to pin down. He was either the victim of a kidnapping or a treacherous perpetrator of the kidnapping. What is undisputed is that he was born in Baghdad, moved to the United States in 1990 with his Romanian-born wife, became a naturalized citizen in 2000 and is the father of three young children.

Three years ago, Munaf was in Bucharest when three Romanian journalists hired him to travel with them to Iraq as a translator and a guide. They were there for only a few weeks when they were kidnapped by an Iraqi insurgent group. They were held captive for two months but were released to the Romanian Embassy in May 2005.

Shortly after, the U.S. military arrested Munaf and held him at Camp Cropper. In August 2006, Munaf filed a writ of habeas corpus in federal district court in Washington. In Baghdad, U.S. officials responded by saying they were going to transfer Munaf to the Iraqis to be tried in a criminal court.

Because Munaf is a Sunni Muslim, his lawyer sought a restraining order, saying his client “faced a real and substantial risk of torture” if he were delivered to the Iraqi authorities.

But U.S. authorities pressed ahead. In Munaf’s petition to the Supreme Court, Margulies said Coast Guard Lt. Robert Pirone “met ex parte with the presiding Iraqi judge for approximately 15 minutes. Immediately thereafter, that judge convicted and sentenced Mr. Munaf to die.”

Back in Washington, his lawyers filed new motions, but Judge Sentelle and the court of appeals for the District of Columbia concluded Munaf’s conviction in the Iraqi court deprived it of jurisdiction. The court did, however, maintain an injunction that barred transferring Munaf to the custody of the Iraqis.

Margulies argues the D.C. court looked to the wrong precedent. Rather than relying on the post-World War II trial of Japanese soldiers, he said Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004), made clear that U.S. citizens—even those captured abroad fighting for the enemy—are entitled to seek habeas relief.

Yaser Hamdi, a Saudi who was born in Louisiana, was captured in Afghanistan in the fall of 2001 and sent to Guantanamo Bay and then to a Navy brig in Virginia. When his case reached the Supreme Court, all the justices agreed he had a right to seek habeas relief. Justice Antonin Scalia went further than most, saying the government had no choice but to try Hamdi for treason or release him. Shortly after the court held that he was entitled to a hearing before a neutral judge, the Defense Department released Hamdi to the custody of the Saudis.

The solicitor general says the two new cases are fundamentally different because Munaf and Omar went to Iraq voluntarily and are being held for crimes committed there.

“When an American citizen commits a crime in a foreign country, he cannot complain if required to submit to such punishments the laws of that country may prescribe,” Clement said, quoting a 1901 precedent, Neely v. Henkel, 180 U.S. 109.

Web Extras:

Boumediene v. Bush briefs

Munaf v. Geren briefs

David G. Savage covers the U.S. Supreme Court for the Los Angeles Times and writes regularly for the ABA Journal.